calsfoundation@cals.org

Japanese American Relocation Camps

After Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, and America’s subsequent declaration of war and entry into World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the War Relocation Authority (WRA), which selected ten sites to incarcerate more than 110,000 Japanese Americans (sixty-four percent of whom were American citizens). They had been forcibly removed from the West Coast, where over eighty percent of Japanese Americans lived. Two internment camps were selected and built in the Arkansas Delta, one at Rohwer in Desha County and the other at Jerome in sections of Chicot and Drew counties. Operating from October 1942 to November 1945, both camps eventually incarcerated nearly 16,000 Japanese Americans. This was the largest influx and incarceration of any racial or ethnic group in the state’s history. One of the sites, Rohwer, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

After Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into World War II, many Americans, especially those living on the West Coast, feared an eventual invasion by the empire of Japan. Over eighty percent of the Japanese American population living in the United States at the time lived along the coast in the states of Washington, Oregon, and California. Many West Coast citizens viewed the concentrated Japanese American communities as potential enclaves for espionage and “fifth-column” activities. Fueled by war hysteria, reinforced by decades of racial hatred, and citing the “doctrine of military necessity,” President Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, signed Executive Order 9066, giving the secretary of war the power to designate military areas from which “any or all persons may be excluded” and authorized military commanders to initiate orders they deemed advisable to enforce such action.

On March 18, Roosevelt created the WRA for the “relocation, maintenance, and supervision” of the Japanese American population. The search for sites for America’s first Japanese American “relocation center,” as they were euphemistically labeled by the WRA, was limited to federally owned lands suitable enough to house from five to eight thousand people and located, as the War Department required, “a safe distance from strategic works.” By June 4, 1942, the WRA had selected ten sites, with the Arkansas camps being the easternmost sites. Arkansas’s Farm Security Administration chief, Eli B. Whitaker, acquired the land for the Arkansas camps. It was situated in the marshy delta of the Mississippi River’s floodplain and was originally tax-delinquent lands in dire need of clearing, leveling, and drainage.

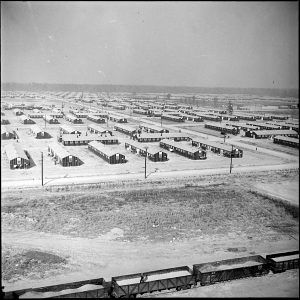

Each camp was approximately 10,000 acres, including 500 acres of tarpapered, A-framed buildings arranged into numbered blocks. All were partially surrounded by barbed wire or heavily wooded areas with guard towers situated at strategic areas and guarded by a small military contingent. Each block was designed to accommodate around 250 people residing in fourteen residential barracks with each barrack (20’x120′) divided into four to six apartments. Each block also consisted of a mess hall, a recreational barrack, a laundry building, and a building for a communal latrine. The residential buildings were without plumbing or running water, and the buildings were heated during the winter months by wood stoves. The camps also had an administrative section segregated from the rest of the buildings, a military police section, a hospital section, a warehouse and factory section, a residential section of barracks for WRA personnel, barracks for schools (kindergarten through twelfth grade), and auxiliary buildings for such things as canteens, motion pictures, gymnasiums, motor pools, and fire stations. Both camps were immense, sprawling cities that were two of the largest agricultural communities in Arkansas. During the construction phase of the incarceration camps, more than 5,000 workers were employed to clear hundreds of acres of land, to build more than 1,200 barrack-type buildings, and to lay miles of gravel-laden roads. The cost to the federal government alone in 1942–43 was $9,503,905.

The Rohwer Camp operated from September 18, 1942, to November 30, 1945, under the project director, Ray D. Johnston, and its peak population reached 8,475. The Japanese American population was divided into classifications known as Issei, first-generation nationals (aliens) precluded from American citizenship by federal immigration laws; Nisei, second-generation American citizens born in this country; and Sansei, third-generation offspring of the Nisei who were also American citizens. Another classification in the camps was the Kibei—American citizens who had received some of their primary years of education in Japan.

Although accurate population and age statistics were in a state of flux due to the WRA’s constant movement of the Japanese American population, the total Rohwer population of 8,475 Japanese Americans in January 1943 indicates well over ninety percent of the adult population had been involved in farming, commercial fishing, or agricultural businesses. Thirty-five percent were Issei (aliens), with ten percent over the age of sixty. Sixty-four percent were Nisei (American citizens), with forty percent under the age of nineteen. There were 2,447 school age children in the camp—a full twenty-eight percent of the total population.

The Jerome Relocation Center operated from October 6, 1942, to June 30, 1944. In operation the fewest number of days (634) of any of the ten relocation camps, Jerome was under the direction of Paul A. Taylor. Eli B. Whitaker, former regional director of both camps in Arkansas, became project director of Jerome during its last few months of operation. Of a total agriculturally based population of 7,932 as of January 1943, thirty-three percent were Issei, with fourteen percent over the age of sixty. Sixty-six percent were Nisei—American citizens—with thirty-nine percent under the age of nineteen. There were 2,483 school age children—a full thirty-one percent of the total population.

On October 1, 1942, the WRA initiated a new, comprehensive “leave” or “resettlement” program for the incarcerated Japanese Americans in the ten relocation camps. All classifications of leaves were subject to specific conditions, guidelines, and security checks, and could be denied or revoked at any time. The WRA’s leave and resettlement program met with limited success; each month usually fewer than several hundred well-qualified, security free, and socially acceptable Japanese Americans were able to clear the elaborate process and earn the right to live in relative freedom outside the camps. As with all relocation centers, the Arkansas camps were mainly able to resettle only the young, college-bound, well-educated, or well-connected Japanese Americans.

Arkansas was neither receptive to nor supportive of the Japanese Americans being incarcerated in the state. Local residents were often hostile to those imprisoned in the camps for reasons beyond the race of the internees. The camps often had amenities that were lacking in the poor, Delta towns that surrounded them: electricity, locally grown food, and more. During their period of confinement, many unfounded and malicious accusations of “coddling,” food hoarding, labor strikes, and disloyalty were aimed at the camps by state political leaders. Governor Homer Adkins and others also resented and feared the Japanese American prisoners. On February 13, 1943, the Arkansas state legislature passed the Alien Land Act “to prohibit any Japanese, citizen or alien, from purchasing or owning land in Arkansas.” This act was later ruled unconstitutional, and after the camps closed, several families remained in Arkansas, though all but one (that of Sam Yada) left within a year’s time to escape the system of peonage that was common for agricultural workers. Governor Adkins was particularly opposed to letting Japanese Americans attend college within the state, fearing that allowing such would pave the way to the integration of higher education in Arkansas. All Arkansas colleges turned away Japanese Americans save the University of the Ozarks in Clarksville (Johnson County), which allowed one Nisei male to enroll in the autumn of 1945, as the war was coming to a close.

Though the state had little use for them, some Japanese Americans found that the federal government wanted them. The same month that Arkansas’s government passed the Alien Land Act, the U.S. Army initiated a forced loyalty and draft program targeting Japanese American prisoners; this program pulled 326 youth from the Rohwer and Jerome camps. Those of age for military service were often conflicted when it came to the possibility of serving. Some were eager for the opportunity to prove themselves to the country of their birth, while others were resentful of being asked to sacrifice their time, and possibly their lives, on behalf of the country that had imprisoned them without cause.

Rohwer was added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 30, 1974, and designated a National Historical Landmark on July 6, 1992, while the Jerome site was added to the Arkansas Register of Historic Places on August 4, 2010. Today, only a few monuments—a small cemetery at Rohwer and a monument to Japanese American soldiers who died fighting for America in World War II—and a few concrete foundations remain. The World War II Japanese American Internment Museum opened in McGehee (Desha County) in 2013.

For additional information:

Abe, Frank, and Floyd Cheung. The Literature of Japanese American Incarceration. New York: Penguin Group, 2024.

Allbritton, Nicole Ashley. “The Women of Japanese-American Internment, with Emphasis on Rohwer and Jerome.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2010.

Anderson, William G. “Early Reaction in Arkansas to the Relocation of Japanese in the State.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 23 (Autumn 1964): 196–211.

Bearden, Russell E. “The False Rumor of Tuesday: Arkansas’s Internment of Japanese-Americans.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Winter 1982) 327–339.

———. “Life Inside Arkansas’s Japanese American Relocation Centers.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 47 (Summer 1989): 170–196.

Blankenship, Anne M. Christianity, Social Justice, and the Japanese American Incarceration during World War II. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

Cash, Taylor. “From Jerome to Dermott: Comparing the Treatment and Experiences of Japanese Americans and German Prisoners of War in Arkansas During World War II.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2022. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/4669/ (accessed December 1, 2023).

Cashion, Scott. “Actions Speak Louder than Words… Sometimes: Reactions to the Wartime Evacuation and Internment of Japanese-Americans at Rohwer and Jerome.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2006.

Chiang, Connie Y. Nature behind Barbed Wire: An Environmental History of the Japanese American Incarceration. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Daniels, Roger. Concentration Camps: North America. Malabar, FL: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co. Inc., 1981.

Densho Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Hathaway, Heather. That Damned Fence: The Literature of the Japanese American Prison Camps. New York: Oxford University Press, 2022.

Hinnershitz, Stephanie D. Japanese American Incarceration: The Camps and Coerced Labor during World War II. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021.

Howard, John. Concentration Camps on the Home Front: Japanese Americans in the House of Jim Crow. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Imahara, Walter M, and David E. Meltzer, ed. Jerome and Rohwer: Memories of Japanese American Internment in World War II Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

Life Interrupted: The Japanese American Experience in WWII Arkansas. https://ualr.edu/cahc/tag/life-interrupted/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

McFadin, Daniel. “Japanese Americans Recall Internment in State.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 5, 2023, pp. 1A, 7A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/may/05/memories-flood-back-for-former-residents-of/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Mizuno, Takeya. “Press Freedom in the Enemy’s Language: Government Control of Japanese-Language Newspapers in Japanese American Camps during World War II.” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 93 (March 2016): 204–228.

Moss, Dori Felice. “Strangers in Their Own Land: A Cultural History of Japanese American Internment Camps in Arkansas, 1942–1945.” MA thesis, Georgia State University, 2007. Online at https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/32/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Rohwer Japanese American Relocation Center. http://rohwer.astate.edu/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Sanders, Kimberly McDaniel, ed. The Art of Living: Japanese American Incarceration Artwork in the Collection of the CALS Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2019.

Schiffer, Vivienne. “Legacies & Lunch: Camp Nine.” October 5, 2011. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Audio online at Butler Center AV/AR Audio Video Collection: Vivienne Schiffer Lecture (accessed July 28, 2023).

Smith, C. Calvin. “The Response of Arkansas to Prisoners of War and Japanese Americans in Arkansas, 1942–1945.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 53 (Autumn 1994): 340–364.

Time of Fear. VHS, DVD. PBS Home Video, 2004.

Twyford, Holly Feltman. “Nisei in Arkansas: The Plight of Japanese American Youths in the Arkansas Internment Camps of World War II.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1993.

“U.S., WWII Japanese Americans Incarcerated in Confinement Sites.” Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/62744/ (accessed May 20, 2024).

Ward, Jason Morgan. “‘No Jap Crow’: Japanese Americans Encounter the World War II South.” Journal of Southern History 73 (February 2007): 75–104.

Watanabe, Caleb Kenji. “Islands and Swamps: A Comparison of the Japanese American Internment Experience in Hawaii and Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2011. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/206/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Welky, Ali, ed. A Captive Audience: Voices of Japanese American Youth in World War II Arkansas. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2015.

Wu, Hui. “Writing and Teaching behind Barbed Wire: An Exiled Composition Class in a Japanese-American Internment Camp.” College Composition and Communication 59, no. 2 (December 2007): 237–262.

WWII Japanese American Internment Museum. McGehee, Arkansas. http://rohwer.astate.edu/plan-your-visit/museum/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Yahata, Craig, and Robert Horsting, directors. Citizen Tanouye. DVD. Hashi Pictures, 2005.

Ziegler, Jan Fielder. “Listening to ‘Miss Jamison’: Lessons from the Schoolhouse at a Japanese Internment Camp, Rohwer Relocation Center.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 33 (August 2002): 137–146.

———. The Schooling of Japanese American Children at Relocation Centers During World War II: Miss Mabel Jamison and Her Teaching of Art at Rohwer, Arkansas. Lewiston, NY: The Mellen Press, 2005.

Russell E. Bearden

White Hall, Arkansas

Camp Shelby Dance

Camp Shelby Dance  Joseph Hunter, portrait by Henry Sugimoto

Joseph Hunter, portrait by Henry Sugimoto  Internment Camp Locations

Internment Camp Locations  Japanese American Internment Museum Anniversary

Japanese American Internment Museum Anniversary  Japanese American Internment Museum

Japanese American Internment Museum  Jerome Buildings

Jerome Buildings  Jerome Relocation Center Hospital Crew

Jerome Relocation Center Hospital Crew  Jerome Relocation Center

Jerome Relocation Center  Jerome Relocation Center

Jerome Relocation Center  Jerome Relocation Center Children

Jerome Relocation Center Children  Jerome Relocation Center School Children

Jerome Relocation Center School Children  Rohwer School

Rohwer School  Rohwer Memorial

Rohwer Memorial  Rohwer Memorial

Rohwer Memorial  Rohwer Relocation Center

Rohwer Relocation Center  George Takei

George Takei  Jamie Vogel

Jamie Vogel

Before my family lived at Rohwer in Arkansas, my father was in Japan, where he was interned during the first part of the war. Daddy sent my mother and my sister back to the States for safety but elected to stay, believing that Christianity was for ALL and had nothing to do with race or nationality. He wanted to stand with his already persecuted Japanese Christian brothers. He was also a conscientious objector (CO). The morning of the Pearl Harbor attack, Daddy’s “guardian angel” came and told him to bring essentials; their nations were at war. The non-Japanese (many Europeans, as well as Americans) were housed on the campus of a Catholic girls’ school located between Tokyo and Yokohama. Some time after the men were interned, they were allowed to request belongings from their homes. Daddy asked for, and received, their baby grand piano, which was enjoyed by all. The day the things were brought to them, Daddy’s “angel” called him out into the hallway and reached under his shirt for a package. He brought out a framed photograph of my mother and sister, which my father had not requested, having a copy in his billfold and not wanting to ask for too much. Daddy was repatriated on the Gripsholm, with the first group of prisoners to be exchanged. When my mother went to New York to meet Daddy, she waited at the hotel as internee after internee arrived, but not Daddy. Our government, knowing Daddy’s status as a CO, had detained him to question him on his loyalty. Daddy finally convinced them that while he would do nothing to further the U.S. war effort, neither would he hinder it or further the Japanese cause. They continued their ministry with Japanese-speaking congregations in Houston before moving to McGehee (and Rohwer).

(2011) Sam Yada and his two sons, Richard and Robert, remained in Arkansas after World War II. The sons still live in Arkansas, Richard in Little Rock and Robert in Fort Smith. Their mother, Mrs. Yada is STILL living, and is in a nursing home in Little Rock. I have interviewed both of them. The Oishi family and the Nakamura family also remained in Arkansas and lived near the Yada family in Scott. In 1957, Scott High School closed because of declining enrollment, and the Nakamura boys and the Oishi boys were bussed to Central High. (YES, in 1957the crisis year). The Oishi parents remained in the area until Mr. Oishi died and his widow went to live with some of her ten children.