calsfoundation@cals.org

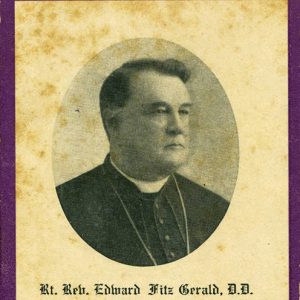

Edward Mary Fitzgerald (1833–1907)

Edward Mary Fitzgerald was the second Roman Catholic bishop of the Diocese of Little Rock, overseeing a diocese that encompasses the boundaries of the state of Arkansas. As the most historically significant Arkansas Catholic prelate, he was one of the only bishops in the world, and the only English-speaking one, to vote against papal infallibility. As an Arkansas bishop, he strove to attract Catholic immigrants to the state and sought also to evangelize African Americans; these efforts, however, bore little fruit. St. Edward Catholic Church was named in his honor.

Although it is known that Edward Fitzgerald was born in the city of Limerick on the west coast of Ireland, his birth certificate fails to reveal his exact date of birth. Various sources give four different dates within the month of October 1833; it may have been on the thirteenth, then the feast day of St. Edward the Confessor. His father, James Fitzgerald, was Irish, while his mother, Joanna Pratt, was of German descent. In the midst of the great Irish potato famine, Fitzgerald migrated with his family to the United States in 1849. The following year, he entered St. Mary of the Barrens Seminary in Perryville, Missouri. Two years later, he became a seminarian at St. Mary’s in Cincinnati, Ohio. On August 22, 1857, Archbishop John Purcell ordained Fitzgerald as a priest for the Cincinnati archdiocese. His first and only assignment as a priest was to St. Patrick’s Church in Columbus, Ohio, where he healed a divisive ethnic schism between the Irish and German immigrants. In 1859, he became an American citizen.

On June 22, 1866, Pope Pius IX notified the thirty-two-year-old priest of his appointment as bishop at Little Rock (Pulaski County). As he was a young man, and perhaps knowing that it was a real mission diocese, Fitzgerald initially rejected his appointment, yet by December, the pontiff sent him a mandamus, an order to accept the Arkansas diocese under holy obedience.

On February 3, 1867, at his parish in Columbus, Ohio, Archbishop Purcell consecrated Fitzgerald Arkansas’s second Catholic prelate; he was now the youngest bishop in the United States. When Fitzgerald arrived in Little Rock on St. Patrick’s Day 1867, he quickly discovered what a civil war and five years without a bishop can do to a diocese. (Arkansas had been without a Catholic bishop since the death of Bishop Andrew Byrne on June 10, 1862.) There were only six priests to serve a financially destitute diocese.

In 1869, Fitzgerald was summoned to Rome to attend the First Vatican Council. There, on July 18, 1870, the Arkansas prelate became a footnote in the history of Catholicism by being one of only two prelates in the universal church to vote against the dogma of papal infallibility. (The only other negative vote came from a bishop in Sicily.) His non placet (“it does not please”) vote was the first after 491 affirmations. When the tally ended, this large-framed Irishman walked up to altar at St. Peter’s and knelt before Pope Pius IX to announce his submission to the council’s decision. Fitzgerald had not been one of the leaders of the opposition, but he, along with three American archbishops and sixteen other Catholic prelates, had signed a document expressing doubts about the wisdom of the declaration of papal infallibility at that time. While most left by the time of the vote, Bishop Fitzgerald decided to stay and make his voice known. Fitzgerald related to a British priest, Father Peter Benoit, in 1875 that he did not go 6,000 miles to do any man’s bidding but to vote according to his conscience. Ten years later, Fitzgerald publicly defended his vote by maintaining that while he had always supported the doctrine, he nevertheless believed that such a declaration at that time would only hamper Catholic evangelism in the United States.

Contrary to common belief, Fitzgerald’s vote on infallibility did not stifle his career. Pope Leo XIII, the successor of Pius IX, appointed Fitzgerald to the archbishoprics of Cincinnati and New Orleans, as well as several other dioceses, yet he stubbornly spurned all offers of promotion or transfer out of the state. His reasons for refusal were both humble and practical; he never seriously desired high positions for himself, and he believed that a new prelate would only take years to learn how to manage and sustain a mission diocese like Arkansas.

His total episcopacy spans four decades, 1867 to 1907. By 1900, the number of Catholic priests had increased from six to forty-three—half diocesan, half from religious orders. In 1867, there were only nine Catholic churches in the state; by the end of the nineteenth century, there were fifty-one parishes, with forty mission stations. In 1867, there had been only one religious order of twenty sisters; thirty-three years later, there were four orders of 150 women ministering throughout Arkansas. Four Catholic medical facilities were opened during his administration. One of Arkansas’s first hospitals would be St. Vincent Infirmary in Little Rock, founded in 1888. By 1900, that hospital was joined by two others, St. Joseph’s in Hot Springs (Garland County) and St. Bernard’s in Jonesboro (Craighead County). In 1905, two years before Fitzgerald’s death, St. Edward’s Hospital opened in Fort Smith (Sebastian County).

Fitzgerald attempted to increase the Catholic population by encouraging foreign immigration into Arkansas. While Irish immigrants still trickled into Arkansas, it was mostly German Catholics who migrated to Arkansas between 1870 and 1890. These immigrants were fleeing Chancellor Otto Von Bismarck’s anti-Catholic policies, known as Kulturkampf or culture struggle. These Germans and Swiss German-speaking Catholics settled along the Arkansas River from Little Rock to Fort Smith and also came as workers along the railroad in northeastern Arkansas. In the mid-1890s, Italian immigrants came to southeastern Arkansas, and many later migrated to the Ozark Mountains in the northwestern corner of the state. His efforts, however, yielded few results. By 1900, Catholics made up just less than one percent of the existing population.

In an effort to convert African Americans, Fitzgerald established Arkansas’s oldest black Catholic parish in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) in 1895. A year later, he had six black Catholic schools in operation, yet only two were left a decade later. White racial prejudices and strong opposition within the black Protestant community to any Catholic evangelization hampered his efforts.

Fitzgerald was recognized nationally by his fellow American Catholic prelates. He gave the opening sermon at the Third Plenary Council in Baltimore in 1884, where he argued the minority position that parishes should not establish schools but only teach the Catholic catechism to the children. He supported the cause of the Knights of Labor and privately expressed his appreciation to Cardinal James Gibbons of Baltimore for his support of labor unions. Pope Leo XIII directed Fitzgerald administer the Diocese of Dallas during 1893 after that prelate suddenly retired. As the senior bishop in the New Orleans province, he represented Archbishop Francis Janssens of New Orleans at a Conference of Archbishops in Philadelphia in 1896.

On January 17, 1900, Fitzgerald’s thirty-three years of active ministry came to abrupt end when he suffered a stroke in Jonesboro; he spent the last seven years of his life as an invalid confined to St. Joseph’s Hospital in Hot Springs. He celebrated his fortieth anniversary as bishop on February 3, 1907, eighteen days before he died. He is buried in a crypt under St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Little Rock, the edifice Fitzgerald helped bring about in 1881. Long overlooked by American Catholic historians, he is undeniably one of the most important Catholic leaders in Arkansas history.

For additional information:

Archives of the Archdiocese of New Orleans. Old Ursuline Convent, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Archives of the Diocese of Little Rock. St. John’s Catholic Center, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“The Bishop from Petricula.” Time, July 27, 1970. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,909531,00.html (accessed January 29, 2024).

Luyet, Gregory T. “Bishop Edward Fitzgerald Was a Reluctant but Ready Servant.” Arkansas Catholic, February 17, 2007, p. 3.

O’Dell, Clay M. “An American Catholic: Edward Fitzgerald, Second Bishop of Little Rock.” MA thesis. Graduate Theological Center, Berkeley, California, 1994.

Petersen, Svend. “The Little Rock Against the Big Rock.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 2 (June 1943): 164–170.

Woods, James M. Mission and Memory: A History of the Catholic Church in Arkansas. Little Rock: August House, 1993.

James M. Woods

Georgia Southern University

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Religion

Religion Fitzgerald Mourning Card

Fitzgerald Mourning Card  Edward Fitzgerald

Edward Fitzgerald  Edward Fitzgerald

Edward Fitzgerald

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.