calsfoundation@cals.org

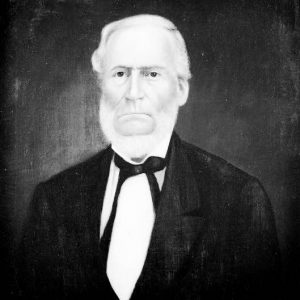

Edward Cross (1798–1887)

Edward Cross, who was born in Tennessee and reared in Kentucky, practiced law briefly in eastern Tennessee as a young man and then moved to southern Arkansas in 1826, where he spent a long career in politics and the judiciary but particularly in land speculation and business. He served in Congress, was the state attorney general for a time, and also served on the state’s highest court—first the territorial Superior Court and then briefly the Arkansas Supreme Court. His stints on the appellate courts earned him little distinction in the eyes of contemporaries, but his business instincts did. He helped form and develop the Cairo and Fulton Railroad, which later became the state’s most prosperous railroad, the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railway Company, which merged into the Missouri Pacific Railroad and finally the Union Pacific Railroad.

Edward Cross was born on November 11, 1798, in Rogersville in the northeastern corner of Tennessee near the Kentucky border. His parents, Robert Cross and Keziah Gillenwater Cross, soon moved to Cumberland County, Kentucky, on the Tennessee border, where Cross went to school. He moved to Overton County, Tennessee, at the age of twenty-one and read law under Adam Huntsman, a political opponent of Davy Crockett, the soldier and politician who became an American folk hero. Cross passed the bar and practiced in Tennessee for about three years before moving to Arkansas, settling in the Marlbrook community near the Hempstead County town of Washington. In 1831, he married Laura Frances Elliott of Washington County, Missouri. Laura Frances was a sister of the wife of Chester Ashley, one of the richest and most prominent men of territorial and pre–Civil War Arkansas. Cross’s connection with a member of “The Family,” the dynasty of early Arkansas political leaders, would prove helpful in his political and business careers. The couple had eight children.

He soon acquired a plantation and slaves and began to engage in land speculation across the state—a lifetime engagement.

At Washington, he formed a law partnership with Daniel Ringo, who would soon move to Pulaski County and form a law partnership with Chester Ashley—an association that helped advance Ringo’s political career, just as the wife-and-sister connection did for Cross. When statehood was achieved in 1836, Ringo would become the first chief justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court.

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson appointed Cross, a lifelong Democrat, as one of the three judges on the Superior Court, the territorial predecessor of the Supreme Court. From 1836 to 1838, he was surveyor general of public lands, and in 1838, he was elected easily to the U.S. House of Representatives, defeating Absalom Fowler (a Whig) while making only a single campaign speech. He was reelected by large margins in 1840 and 1842, but he did not run again in 1844 because he apparently did not like Washington DC.

In 1845, Governor Thomas S. Drew appointed Cross to a vacancy on the state Supreme Court when Justice Thomas J. Lacy retired owing to poor health. Cross served only a year and a half. Judge J. W. Looney, the Supreme Court biographer, described Cross as mediocre, both as a lawyer and judge and as a politician. In a letter to President James K. Polk, Governor Archibald Yell described Cross as “a poor electioneerer [sic],” and Looney said Cross’s opinions on both the Superior Court and Supreme Court were not especially noteworthy. His best-known opinion was Grande v. Foy (1831), which dealt with the adoption of common law in the Arkansas Territory. Federal judge Morris K. Arnold of the Eighth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, a historian of early Arkansas, said Cross’s opinion was an important contribution to the development of the law but was “discursive and somewhat incoherent.”

Most of the decisions of the court during his brief service tended to be routine matters about probate and debts. One decision, however, is particularly notable: Pendleton v. The State, 6 Ark. 509, in which the Supreme Court ruled on the constitutionality of an 1843 statute that restricted the movement of free Blacks into Arkansas. In an opinion written by Justice Cross, the court upheld the law and said the Arkansas constitution “was the work of the white race” and that Blacks could never be considered citizens with the constitutional right of free movement. Cross continued: “The two races differing as they do in complexion, habits, conformation and intellectual endowments could not nor ever will live together upon terms of social or political equality. A higher than human power has so ordered it, and a greater than human agency must change the decree.”

Cross left the Supreme Court in 1847 and never engaged in public service again, except for a very brief appointment as acting attorney general by Governor Augustus Garland. He devoted the last forty years of his life to what he did best—building businesses and developments and making money. Cross championed making internal improvements across the state, partly by the development of rail. He and a group of partners, notably Roswell Beebe, who had obtained the patent to establish Little Rock (Pulaski County), acquired a claim on New Madrid lands at Fulton (Hempstead County) on the Red River close to Cross’s home. They intended to make it a major community on the way to Texas and Mexico with streets, homes, a hotel, and warehouses. Steamboats stopped at the town, unloading passengers and supplies and loading cotton from the Cross plantation and others. In 1852, the federal government approved federal funding for rail lines connecting the Red River with Little Rock and Memphis. One of the rail lines was the Cairo and Fulton. Cross became president of the railroad in 1855 and served until the outbreak of the Civil War. After the war, it merged with the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern. Cross was still an owner but not active in the railroad’s management.

His home at Marlbrook apparently was a showplace. G. W. Featherstonhaugh, a geologist, historian, traveler, writer, and perhaps the most widely quoted man in Arkansas histories, visited Marlbrook and described it as having “a rare rug, a warm fireplace, and—surprise—a piano.”

Cross died on April 6, 1887. He is buried at Marlbrook Cemetery near his estate along with his wife, at the foot of an Indian mound. The tombstone was a simple shaft of granite with his and his wife’s names, birthdates, and death dates, along with the words, “Loved and honored they lived and now sleep in Jesus.”

For additional information:

Bridges, Ken. “The Interesting Career of Judge E. Cross.” Camden News, September 25, 2015.

Hallum, John. Biographical and Pictorial History of Arkansas, Vol. I. Albany, NY: Weed, Parsons & Co., Printers, 1887.

Hempstead, Fay. A Pictorial History of Arkansas from Earliest Times to the Year 1890. St. Louis, MO: Thompson Publishing Company, 1890.

Looney, Judge J. W. “Edward Cross.” Arkansas Lawyer 50 (Summer 2015): 44.

Stafford, L. Scott. “Slavery and the Arkansas Supreme Court.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Journal 19 (Spring 1997): 413–464. Online at https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1729&context=lawreview (accessed October 21, 2023).

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.