calsfoundation@cals.org

Contraband Camps

aka: Slave Refugee Camps

In 1862, as a response to Confederate use of slave labor against the Federal army in Arkansas, Union general Samuel R. Curtis drew on the authority of earlier “confiscation” acts to free black slaves for use in the Union army. Issuing certificates of freedom to hundreds of “contraband” fugitives (meaning escaped or Union-freed slaves), Curtis laid the foundation for emancipation in Arkansas, and he was one of the more determined Union military leaders in the belief that slaves should be freed.

Word spread among Arkansas’s slaves, and when Curtis’s army arrived at Helena (Phillips County) in the summer of 1862, more than 2,000 came with him hoping for freedom and protection. Helena would be occupied by Federal forces through the war’s end, and the area became the most important refugee center in Arkansas for escaped slaves. Colonel John Eaton was placed in charge of various contraband camps throughout eastern Arkansas.

President Abraham Lincoln’s initial Emancipation Proclamation, announced in September 1862, warned Confederates still in rebellion that their slaves would be freed by the U.S. government starting in January 1863. With this act, the Civil War evolved from a fight to preserve the Union to a fight for freedom. From 1863 onward, the number of contraband camps and other refugee centers for former slaves in Arkansas increased.

In May 1863, a Quaker man named Levi Coffin visited Helena, where he met with an old neighbor, William Shugart. Coffin wrote that he found 3,600 contrabands in Helena working either in the service of the government or as farmers. Many blacks were living in three large churches, while others found shelter in houses and in tents. Coffin referred to other camps between Helena and Vicksburg, Mississippi, among them Camp Deliverance, Camp Wood, and Camp Colony. However, shortly after Coffin’s visit, these camps were attacked by the Confederates, and many blacks perished in the burning cabins in which they were housed.

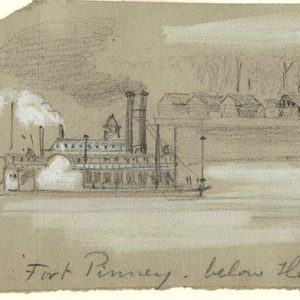

Nonetheless, the contraband settlements around Helena formed the basis for Union recruiting efforts aimed at thousands of able-bodied freedmen, and the first of six black Arkansas volunteer regiments was organized at Helena beginning in April 1863. Ultimately, more than 5,500 black volunteers from Arkansas served in the Union military. Former slaves supplied crucial manpower so that Union forces engaged against Confederates elsewhere would not be needed to fight in Arkansas. Other contrabands earned wages working for the army, for civilians in Helena, and on plantations outside of town. By 1864, four camps housed most of Helena’s former slaves—Helena, Island 63 (in the Mississippi River), Freedmen’s Fort, and Fort Pinney.

By late 1863, Union forces also occupied other parts of Arkansas, and contraband camps soon emerged around the state. For example, Home Farm, near Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), attracted many refugees and freedmen after the Emancipation Proclamation. Other informal camps or refugee centers existed after 1863 in Desha County, DeValls Bluff (Prairie County), Lick Skillet (Monroe County), and Magnolia (Columbia County). Most of these camps contained fewer than 2,000 former slaves at any given time, but with military aid they also formed the basis of Union recruitment of many more black soldiers.

Northern charitable organizations—including the American Missionary Association, the Western Sanitary Commission, the North Western Freedmen’s Aid Commission, and the Indiana Yearly Meeting of the Society of Friends (Quakers)—sent food, medicine, doctors, nurses, and teachers to the various freedmen camps in Arkansas. The former slaves took advantage of whatever opportunities given them to survive, whether by growing vegetable gardens or finding jobs with the army. Men worked as laborers, building Fort Curtis and the earthworks near Helena. Contrabands worked as stable hands, teamsters, personal servants, and cooks. Women cooked, cleaned, and washed and mended clothes for officers and enlisted men. However, freed blacks were frequently not adequately compensated for the work they did under white supervision. Most contraband camps suffered from poor sanitation. The Union army tried to ameliorate these conditions by setting up a system that included a hospital, with at least one surgeon to administer to the former slaves. Contrabands also endured theft and violence at the hands of whites.

With continued Union occupation throughout Arkansas, philanthropists from the North increased their efforts to aid the former slaves. However, the spread of Union control took time. Even as Little Rock (Pulaski County) came under control of Union forces in September 1863, it was not until June 1865 that Confederate holdouts based in Hempstead County officially surrendered to the Union army. By the end of 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment had freed any remaining slaves in the state.

After the war, freedmen worked with the American Missionary Society to start schools for the education of blacks, who had formerly been prohibited from learning to read and write. By 1875, Professor Joseph C. Corbin had opened Branch Normal College, a school primarily for the training of teachers for black schools, as part of Arkansas Industrial University. Branch Normal was not far from the former contraband camps at Pine Bluff. Arkansas’s first historically black public college is today the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff.

The creation of freedmen’s “home farms,” also grew out of efforts at organizing former slaves in the contraband camps. At least four home farms were established during the war, at Little Rock, DeValls Bluff, and Pine Bluff, as well as near Helena. The land for these farms was leased from whites, and the colonies were economically self-supporting through crop sales. The farms also depended upon nearby Union detachments for protection.

The National Park Service designated Freedom Park, in historic Helena, as a Network to Freedom site. The site includes five major exhibits exploring the experience of contraband slaves during and after the Civil War.

For additional information:

Christ, Mark K. Civil War Arkansas, 1863: The Battle for a State. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010.

Coffin, Levi. Reminiscences of Levi Coffin. New York: Arno Press, 1968.

Cooper, Abigail. Interactive Map of Contraband Camps, History Digital Projects, University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons. http://repository.upenn.edu/hist_digital/1/ (accessed October 19, 2020).

Eaton, John, Jr. Grant, Lincoln and the Freedmen, Reminiscences of the Civil War. New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1907.

Finley, Randy. From Slavery to Uncertain Freedom: The Freedmen’s Bureau in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

Gerteis, Louis. From Contraband to Freedman: Federal Policy Toward Southern Blacks, 1861–1865. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1973.

Greenberg, Brooke. “In the Midst of War: Meet the Women Who Came to the Aid of Those in Helena’s Contraband Camps.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 18, 2025, pp. 1H, 6H. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2025/may/18/931f4e93/ (accessed May 19, 2025).

Moneyhon, Carl. H. “The Little Rock Freedmen’s Home Farm, 1863–1865.” Pulaski County Historical Review 42 (Summer 1994): 26–35.

Poe, Ryan M. “The Contours of Emancipation: Freedom Comes to Southwest Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Summer 2011): 109–130.

Taylor, Amy Murrell. Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Ryan Jordan

National University

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Freedmen's Schools

Freedmen's Schools ACWSC Logo

ACWSC Logo  "Contraband" Fugitives

"Contraband" Fugitives  John Eaton

John Eaton  Fort Pinney

Fort Pinney

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.