calsfoundation@cals.org

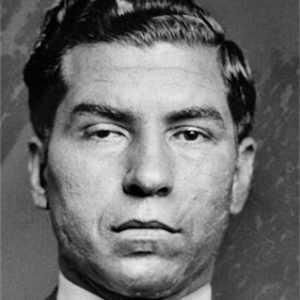

Charles "Lucky" Luciano (1897–1962)

aka: Salvatore Lucania

Charles “Lucky” Luciano was an Italian-American gangster who was said by the FBI to be the man who “organized” organized crime in the United States. In many ways, he was the model for the character Don Corleone in the popular book and movie, The Godfather (1972). He evaded arrest and survived attempted gangland assassinations only to meet his downfall in 1936 while vacationing in Hot Springs (Garland County).

Luciano was born Salvatore Lucania on November 24, 1897, in Lercara Friddi, Sicily, the third of five children to Antonio Lucania and Rosalie Capporelli Lucania. His mother kept house, and his father worked in the sulfur mines as well as doing whatever work he could find in the poor hillside village near the town of Corleone.

When Lucania was ten, the family moved to a tenement flat in the Lower East Side of New York City, New York. While a schoolboy, Lucania wanted money to escape poverty. After working low-paying jobs such as being a delivery boy, he began demanding that younger children on their way to and from school pay him their lunch money as “protection.” He met a Jewish boy named Meyer Lansky who refused to be bullied, and they became lifelong friends.

As a teenager, Salvatore changed his name to Charles because he thought the nickname Sal or Sally was not masculine. He later changed his last name to Luciano because he felt it was easier for Americans to pronounce.

During Prohibition in the 1920s, Luciano became a bootlegger and was involved in illegal gambling. His friend and fellow gangster Lansky nicknamed him “Lucky” in 1929 after Luciano survived a gangland assassination attempt (Luciano also had a reputation for being lucky at gambling). Luciano became the acknowledged leader of the nationwide underworld, and he called his organized crime syndicate “The Commission” or “The Outfit.” He divided New York City among the “Five Families” (Bonanno, Colombo, Gambino, Genovese, and Lucchese) and the rest of the country among twenty-four respective criminal gangs. Though he declined the official title of “Capo di Tutti Capi,” or “Boss of all Bosses,” his command was unquestioned.

In the early 1930s, Luciano lived in a penthouse suite at New York’s Waldorf Towers, where he was registered as Charles Ross. In March 1936, Luciano fled New York after being alerted by a friendly desk clerk that two men who looked like detectives were on their way up to see him. He drove to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, changed cars, and borrowed $25,000 from friends. He then drove to Cleveland, Ohio, where he took the train to Hot Springs, which at the time was a gambling sanctuary run by fellow gangster Owen “Owney the Killer” Madden.

While in Hot Springs, Luciano stayed in a large suite at the luxurious Arlington Hotel. He went to the horse races at Oaklawn Park racetrack almost every day. Most afternoons, he gambled at casinos near the Arlington, especially the Southern Club. In the evenings, he and his companion Gay Orlova often dined and danced at the Belvedere Club just outside Hot Springs. Sometimes they were the dinner guests of Owney Madden.

One morning, Luciano took a stroll along Central Avenue and Bathhouse Row after he had been in Hot Springs for about two weeks. New York special prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey had proclaimed Luciano “Public Enemy Number One” and started a nationwide manhunt to arrest Luciano and return him to New York to face indictment for allegedly running a $12 million prostitution syndicate. Luciano was originally charged with ninety counts of compulsory prostitution, later reduced to sixty-two.

New York detective John J. Brennan went to Hot Springs on an unrelated case and, on April 1, 1936, saw Luciano strolling along Bathhouse Row with Hot Springs’ chief of detectives. Brennan approached Luciano and invited the gangster to return with him to New York. Luciano declined, saying that he was having a good time in Hot Springs.

New York authorities asked Hot Springs and Arkansas officials to extradite Luciano to New York, and he was arrested on April 1, 1936. However, a local judge released Luciano after setting a $5,000 bond. An enraged Dewey contacted Governor J. Marion Futrell and state attorney general Carl E. Bailey, demanding action. Futrell ordered Hot Springs officials to re-capture Luciano, but Hot Springs officials were reluctant to begin extradition hearings. Bailey issued a fugitive warrant on April 3 and ordered Luciano transported to Little Rock (Pulaski County), sending twenty state troopers to Hot Springs to collect Luciano. They removed him from the Hot Springs jail at midnight and rushed him to Little Rock.

A man claiming to be an associate of Madden’s allegedly approached Bailey and offered him $50,000 (ten times his yearly salary) to make sure the extradition was denied. As the extradition hearing was being held in the governor’s conference room on April 6, Bailey made the bribery attempt public, saying Arkansas was not for sale: “Every time a major criminal of this country wants asylum, he heads for Hot Springs. We must show that Arkansas cannot be made an asylum for them.” Bailey’s revelation led to Futrell’s upholding the extradition warrant. Within days, Luciano was returned from Arkansas to New York to stand trial.

On June 18, 1936, Luciano was sentenced to thirty to fifty years at the maximum security Dannemora Prison in New York. It was the longest sentence ever handed down in New York for compulsory prostitution.

He served his time quietly, determined to be a model prisoner. During World War II, Luciano allegedly helped the government by forging ties and collecting intelligence in Sicily prior to the Allied invasion of Italy. He also claimed that he helped prevent maritime sabotage by the enemy in the United States through his connections on the waterfront. In 1946, his sentence was commuted, and Luciano was deported to Italy, as he had never become an American citizen. The U.S. government blocked his attempts to return to the Americas, including Cuba, and he lived the rest of his days in Italy.

While he had several long-term mistresses in the United States and Italy, he never married and claimed no children. Luciano died of a heart attack on January 26, 1962, at Capodichino Airport in Naples, Italy, where he had gone to meet a Hollywood movie producer. Though Luciano was denied entry into the United States during his lifetime, he was buried at St. John’s Cathedral Cemetery in Queens, New York.

For additional information:

Allbritton, Orval E. The Mob at the Spa: Organized Crime and its Fascination with Hot Springs, Arkansas. Hot Springs, AR: Garland County Historical Society, 2011.

Buchanan, Edna. “Lucky Luciano.” Time. December 7, 1998, pp. 131–32.

Gosch, Martin, and Richard Hammer. The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1974.

Ledbetter, Calvin Jr. “Carl Bailey: A Pragmatic Reformer.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Summer 1998): 134–159.

McMath, Sid. Promises Kept. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Reppetto, Thomas. American Mafia: A History of its Rise to Power. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 2004.

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

This information is very useful for my school assignment about big mafia bosses.

Luciano was a citizen. He had to agree to be deported to get out of jail.

Charles did have a child. Whether he took care of him or not is another story.