calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas Real Estate Bank

In 1836, the establishment of the Real Estate Bank of Arkansas became the initial act to pass the first state legislature. Momentum for a state-sponsored bank began during the territorial phase when planters and other lowland agricultural interests sought ways to enhance the availability of capital. The bank’s charter required the state to issue $2 million in five-percent bonds, the proceeds from which would serve as the bank’s capital. But the state held no authority for immediate supervision of the bank’s operations other than the appointment of a minority of the bank’s directors. From 1836 to 1855, when the state took over control, the Real Estate Bank proved to be a source of political corruption, financial mismanagement, and intense sectional conflict among politicians.

Like its sister institution, the Arkansas State Bank, the Real Estate Bank enjoyed bipartisan support. Anthony H. Davies and John Ringgold, both prominent Whigs, wrote the bank’s charter, and the Democratic legislature approved it. Other than being a product of the surge of new banks established in the country at the time, the bank’s stated purpose was to promote the interests of lowland planters. It would have four branches: the headquarters in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and branches in the cotton belt areas of Columbia (Chicot County), Helena (Phillips County), and Washington (Hempstead County). The state appointed one-fourth of the board of directors, and stockholders elected the rest. Each branch had a local board of directors based on a similar formula.

Subscribers to the bank’s stock totaled 325 people, and most were leading men in the state, including Anthony H. Davies, Horace F. Walworth, and U.S. Senator Ambrose H. Sevier—all Chicot County planters. Most stockholders lived in counties bordering the Mississippi or Red rivers, with more than twenty-five percent of all stock owned by twenty-eight men in Chicot County. Subscribers typically bought stock by mortgaging land, which was appraised far above its market value. In turn, they borrowed up to half of the value of their stock, capped at $30,000.

Accusations of favoritism and spoilage in the Real Estate Bank dominated the 1837 legislative session. One critic, Joseph J. Anthony, a representative from Randolph County, wrote a resolution attacking the bank as a source of special privilege. House Speaker John Wilson, who was also president of the bank, defended its operation and vouched for its financial integrity. On December 4, during a debate on a bill to encourage the taking of wolf pelts, Anthony sarcastically alluded to Wilson’s connections to the bank, after which Wilson killed Anthony with a bowie knife on the House floor. Wilson’s friends secured a change of venue for his trial so that his acquittal was assured.

After that, Anthony H. Davies became bank president and authorized T. T. Williamson and Sevier to float bank bonds in New York City, New York, to raise specie and paper issued by stable banks in other states. But most of the bonds were sold to the North American Banking and Trust Company and the U.S. Treasury. Sevier and his relatives continued to exercise great influence over the bank and benefit from its operation through the early 1850s.

With subscriptions, specie, and acceptable bank notes now available, the Real Estate Bank opened for business December 10, 1838, in Little Rock, and the other branches opened the next spring. By November 1839, all branches had suspended specie payments so that bank officials could issue far more credit than was held in reserve. Within a year, the bank’s circulation increased from $153,910 to $759,000. Bank officials followed a fractional reserve policy whereby bank notes exceeded the amount of specie on deposit. When coupled with mismanagement, the bank’s lending policy flooded the market with bank notes, whose value depreciated. By the end of the first year of operation, interest payments came due on the bank’s bonds. To alleviate the crisis, bank officials skirted legality and took out a $121,000 loan from the North American Bank and Trust Company of New York.

Additional pressure on the bank came from small debtors, who believed bank officials discriminated against them in favor of large landowners and stockholders. One example, the Phillips County uprising of May 1841, closed the circuit court of Judge Isaac Baker, who planned to auction seized land of small debtors who had defaulted.

In April 1842, the central board of directors passed a deed of assignment allocating the bank’s assets to fifteen trustees, who replaced local branch boards and eliminated all state appointees. It was hoped the transfer would bring fiscal restraint to the bank, redeem depreciating paper, and pay interest for the state bonds used for capitalization. But the trustees, mostly Democrats, stifled outside surveillance of the bank’s activities. Whigs as much as Democrats feared a full investigation of the bank’s activities, but each side continued to blame the other for the bank’s mismanagement. Still, in January 1843, the General Assembly passed a liquidation act to legalize the assignment policy. The bank continued to function until April 1855, when the state assumed control of its assets and ordered a reckoning of its accounts.

By the late 1840s, the Arkansas General Assembly followed many other states in imposing stiff constitutional regulations on the relationship between government officials and banking.

For additional information:

Schweikart, Larry. “Banking in Antebellum Arkansas: New Evidence, New Interpretations.” Southern Studies 26 (1987): 188–201.

Worley, Ted. R. “The Arkansas State Bank: Ante-bellum Period.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 23 (Spring 1964): 65–74.

————. “The Control of the Real Estate Bank of the State of Arkansas, 1836–1855.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 27 (December 1950): 403–426.

Worthen, W. B. Early Banking in Arkansas. Little Rock: Democrat Printing Co., 1906.

Carey M. Roberts

Arkansas Tech University

Business, Commerce, and Industry

Business, Commerce, and Industry Harris, Carey Allen

Harris, Carey Allen Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Politics and Government

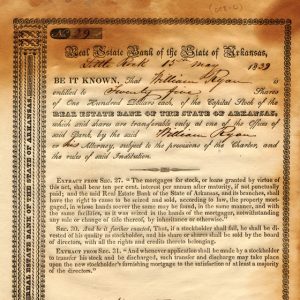

Politics and Government Arkansas Real Estate Bank Stock Certificate

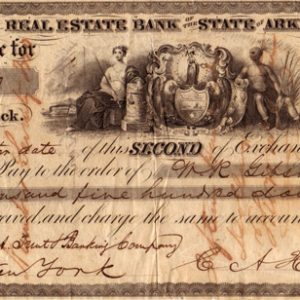

Arkansas Real Estate Bank Stock Certificate  Arkansas Real Estate Bank Draft

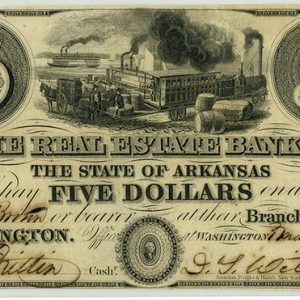

Arkansas Real Estate Bank Draft  Real Estate Bank Note, 1840

Real Estate Bank Note, 1840

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.