calsfoundation@cals.org

Carey Allen Harris (1806–1842)

Carey Allen Harris played vital, though scandal-plagued, roles in the history of early Arkansas banking and Indian Removal between 1837 and 1842.

Carey Allen Harris was born in Williamson County, Tennessee, on September 23, 1806. His parents were Edith Perrin Harris of Virginia and Andrew Harris of Rowan, North Carolina. Much like William Woodruff, founder and editor of the Arkansas Gazette, Harris began his professional life as a printer and newspaper owner in Tennessee, when Harris and Abram P. Maury founded the Nashville Republican in 1824. (Harris went on to marry Maury’s daughter, Martha, and they had four children.) In 1826, Harris and Maury sold the paper to state printers Allan A. Hall and John Fitzgerald.

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which called for “an exchange of lands with the Indians and their removal to lands west of the Mississippi River.” Removal began in 1831 with the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, which called for the removal and subsistence of the Choctaw living in the southeastern states. Just a few years later, Harris began working in the War Department as a clerk under Lewis Cass. When Cass was away, Harris also acted as commissioner of Indian Affairs and as secretary of war until Cass returned to his post. Like Secretary Cass, Harris was a part of President Andrew Jackson’s inner circle. Because of Harris’s connections and open access to Jackson, he was made commissioner of Indian Affairs on July 4, 1836. The next president, Martin Van Buren, retained Harris as commissioner.

An incriminating letter involving Harris and the immediate purchase of $200,000 of Indian rations sent to Arkansas depots surfaced in April 1837. Harris had ordered Lieutenant J. B. Grayson to make the purchase and sell the rations on open market in New Orleans, Louisiana, which violated official policy because rations were supposed to be bought only under orders from the Secretary of War, not from an open market. In Little Rock (Pulaski County), Chief Disbursement Agent Richard D’Cantillon Collins defended Harris in a letter dated April 26, 1837. Collins stated that Harris’s immediate purchase of rations was to “guard against any failure of supplies by contractors or otherwise.” Despite this direct violation of subsistence policy, Harris remained commissioner of Indian Affairs until more accusations came a year later.

On October 19, 1838, Harris resigned his post at the Office of Indian Affairs after yet another incriminating letter surfaced describing his fiscal irresponsibility with federal funds. The letter, which had been accidently mailed by Harris’s wife, indicated that Harris and a friend of his, Thomas J. Porter of Mississippi, were trying to buy Chickasaw lands. Harris was using his position to engage in land speculation, and when President Van Buren asked Harris to explain himself, he resigned rather than face any punishment.

Harris’s resignation soured another deal. After leaving Arkansas, Harris’s associate Jacob Brown went to Washington DC to acquire $300,000 in Chickasaw orphan funds to be invested in Arkansas State Bank bonds. The bank made only about one-third of what was promised to it by Harris, and the profits went to establish branch banks in Fayetteville (Washington County) and Batesville (Independence County). Brown and Harris’s tampering with the Chickasaw Fund netted at least $115,000 of Chickasaw money that was ultimately used to kickstart the Real Estate Bank of Arkansas as well.

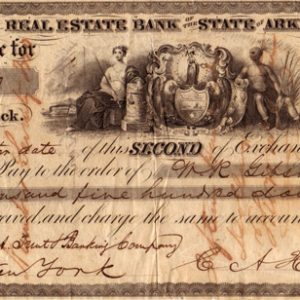

Harris was elected cashier of the Little Rock branch of the Real Estate Bank of Arkansas on November 30, 1838, according to the Daily National Intelligencer, though the Arkansas Gazette had reported Harris’s ascension to cashier of the Little Rock branch of the Real Estate Bank on November 7, 1838. The Enquirer of Richmond, Virginia, reported that his salary was the exact amount he had been making as commissioner of Indian Affairs and the highest of any other bank officer. Starting in 1838, Harris signed every check and stock certificate from the Little Rock branch.

Harris personally oversaw the transfer of Chickasaw money to the Arkansas State Bank in Little Rock. Harris’s approach to Indian affairs was vastly different from that of his predecessors at the Office of Indian Affairs in Washington DC, as he sought speedy and profitable removal of the Indians with little regard for their welfare. In fact, when the Seminole were on the move in 1836, Commissioner Harris helped white families take black slaves away from the Indians. He also worked directly with land speculators in the southeastern states to help them take land away from the Creek during their removal.

On November 2, 1839, the Real Estate Bank’s central office in Little Rock—quickly followed by its satellite branches in Fayetteville, Batesville, Helena (Phillips County), and Columbia (Chicot County)—suspended all payments of specie (money in the form of coins, not notes). On November 24, 1840, following the resignation of William Woodruff as Real Estate Bank president, Harris took his place. As president, Harris said that “as long as the bank paid specie, it was found impossible to keep out as much money as the public wants and the business of the country rendered proper.” This meant that all banks in Arkansas had stopped paying out in gold and silver until enough of it could be recovered to back its paper notes, as per federal law.

In July 1841, Richard D’Cantillon Collins died at his home in Little Rock, prompting an investigation of his accounts by the Committee on Public Expenditures and the Office of Indian Affairs, which sent fellow agent Ethan Allen Hitchcock out to investigate rumors of fraud and corruption related to Indian Removal through Arkansas and Indian Territory. Hitchcock arrived in Little Rock in March 1841, where he reported meeting Luther Chase, Collins’s former clerk at the Arkansas State Bank, on Simeon Buckner’s steamboat, the DeKalb. Harris avoided any more trouble in Arkansas by returning to his home in Franklin, Tennessee. Because of his close ties to President Andrew Jackson, Harris was never prosecuted for his actions. The War Department supposedly destroyed all records of his actions as commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington DC.

Harris died on June 16, 1842, at the age of thirty-six—two months after Hitchcock’s report was filed. The Arkansas Gazette did not report the death until July 6, 1842.

In 1855, Governor Elias Nelson Conway and the Arkansas General Assembly launched an investigation to “bring to light the true condition of the Real Estate Bank of Arkansas.” Conway appointed economist William Gouge and future Arkansas governor William Read Miller to audit the bank. Gouge and Miller’s report, which was finished in October 1856, said that Harris and other members of the bank’s board of directors had the bank suspend specie payments at a time when they possessed a surplus of gold, not a shortage, as Harris had reported in late 1839. Gouge and Miller alleged that the officers “were paid one dollar in specie for every two or three in Arkansas notes.” In the books of the Real Estate Bank and the Arkansas State Bank, those men labeled specie as “Good Money,” while Arkansas notes were referred to as “Bad Money,” because they knew its value was subject to change, whereas gold or silver kept its value much better than paper notes.

For additional information:

Clayton, W. W. History of Davidson County, Tennessee; with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Philadelphia, PA: J. W. Lewis & Company, 1880.

“Died.” Arkansas Gazette, July 6, 1842, p. 3.

Paige, Amanda, Fuller Bumpers, and Daniel F. Littlefield. Chickasaw Removal. Ada, OK: Chickasaw Press, 2010.

Worthen, W. B. Early Banking in Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas Bankers’ Association, 1906.

Cody Lynn Berry

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Business, Commerce, and Industry

Business, Commerce, and Industry Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Politics and Government

Politics and Government Arkansas Real Estate Bank Draft

Arkansas Real Estate Bank Draft

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.