calsfoundation@cals.org

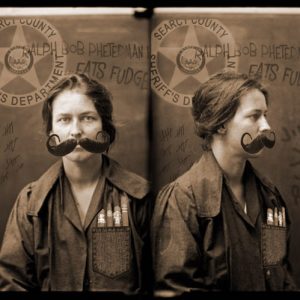

Breeches Panic (1910s)

2020 April Fools' Day Entry

What is now called the “breeches panic” of the 1910s centered upon the fear amongst some men in the state that women, prior to the implementation of female suffrage for Arkansas party primaries in 1918 and nationally in 1920, were accessing the ballot by dressing in men’s clothes. The panic resulted in a number of state and local ordinances intended to ensure the “purity” of the ballot, including medical examinations at all polling places; this also indirectly ensured the (albeit temporary) success of Prohibition.

The exact origin of the breeches panic is vague, and the whole thing may have been based upon an incident that never actually occurred. The Arkansas Gazette, on September 19, 1910, reported on its back pages the following: “A passing traveler tells us that the community of Warren in Bradley County was the scene of an attempted revolution earlier this month when a member of the fairer sex entered a polling site clad in her husband’s breeches and work shirt and possessed of his poll tax receipt. The ruse, however, was quickly discovered, and the Gazette will pass along more information as we hear it.” Historians have sifted through local newspapers from the time period to find more information on the event in question, to no effect.

However, this rumor quickly gained political traction. The suffrage movement had been growing in Arkansas—in fact, the following year, the Political Equality League would be founded, joining such organizations as the Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association. These groups pursued their goals through political advocacy, letter writing, and public rallies, while generally avoiding acts of civil disobedience. Nevertheless, a conservative backlash to women’s suffrage was growing in Arkansas, and this rumored attempt at ballot access by deceptive means provided a handy target for suffrage’s opponents.

In 1911, state representative M. O. Penix of Boone County was the first to seize upon the rumor for political purposes. Penix had long been a proponent of prohibition, and he latched on to this particular rumor in order to advance his ideology. In one speech before the Arkansas General Assembly, he railed, “So long as intoxicating beverages are readily available to the consumer, the chance exists that some mischievous matron might liquor up her husband and assume his place in line on voting day. I tell you, women accoutered with liquor constitute a greater threat to the sanctity of our self-government than does the socialist!”

However, although there was significant sympathy for Prohibition at this time, his proposals failed to pass. In fact, Penix’s rhetoric was put to use against him in 1912, and he lost his bid for reelection. Anti-liquor forces lamented his defeat and took out an advertisement in the Arkansas Democrat praising him for his stance against female suffrage, adding, “We need M. O. Penix in politics!”

Despite the electoral decline of Penix, the year 1912 witnessed conservative politicians generating greater paranoia about the possibility of cross-dressing for political purposes, especially as the election came nearer. In this environment, the figure of the “Warren Woman” became a regular punching bag. “The Warren Woman wants more than she is entitled to by virtue of her sex,” ran one editorial in the Mansfield American, adding, “Give her the opportunity to serve as a voter, and she will next wish to rule as a president!” Various local officials, likewise, began to lambast the idea of women having a political role in Arkansas. “The most intelligent woman is no equal even to a doddering old man whose mental acuity has long since abandoned him,” insisted the mayor of St. Joe (Searcy County).

In fact, worries about women illicitly gaining the vote began to broaden into a general fear of women penetrating men’s spaces in disguise. During the 1913 General Assembly, state senator Madison K. Moran of Lonoke County wrote a so-called “outhouse bill” that would make it a felony for any woman to enter, “for purposes of relieving herself, those toilet facilities specifically designated for use by the male sex.” However, the bill was defeated, largely due to the votes of legislators from poorer and more rural districts. Senator C. T. Cockburn of Montgomery County, for example, remarked on the floor of the Senate, “Must every single-room school of two dozen students build a second outhouse solely to still the fevered imaginings of this Moran?”

During the General Assembly of 1915, the breeches panic reached its zenith in Arkansas with two pieces of legislation, one of which was to have a longstanding effect upon the state. First, the legislature passed the Newberry Act, essentially banning the manufacture and sale of alcohol in the state. This was the goal Senator Penix had attempted to achieve back in 1911, and the debate upon the issue was heavily influenced by a manufactured fear of women using alcohol to appropriate their husbands’ political powers.

The second piece of legislation was much more controversial and, in the end, quite short-lived. State representative Albert B. Bishop of Little River County put forward legislation that would require a simple physical examination to determine “that each elector seeking access to the ballot was appropriately equipped with the physiology necessary to cast such a ballot.” The bill contained few specifics about how this was to be accomplished, and Bishop stated to the press that he did not wish to impose mandates upon county governments but stated that the easiest way “might be to have a room dedicated to the procedure at each polling place in order to limit the necessary embarrassment.”

Despite the fact that many representatives and senators balked at this idea, and many newspapers opined against it, the sheer weight of the current panic made the bill dangerous to vote against, at least for any politician who valued his political survival. The bill passed overwhelmingly in both houses of the Arkansas General Assembly and was signed, albeit reluctantly, by Governor George Washington Hays on April 1, 1915.

Almost immediately, Arkansas became a target for national ridicule. An editorial in the Philadelphia Inquirer observed: “Not every man in Arkansas might have an Abraham Lincoln to support come election time, but he must be proven to possess an Andrew Johnson before he can even cast his ballot!” Some of the more satirical magazines of the day imagined that Arkansas’s vote authentication measures would mirror the “Trials by Congress” of pre-Revolutionary France, wherein men who were accused of impotence by their wives would be forced to prove their virility before assembled experts. One published editorial cartoon features a woman sticking her head out the window of a structure labeled “House of Ill Repute,” shouting to a group of men labeled “County Officials”: “This group checks out! Send in the next round of voters!”

When Rep. Bishop was confronted with what many voters regarded as the “indignity” of the new procedure, he often made things worse for himself. “If men fear that too much time will be consumed by the new process,” he said to the Arkansas Gazette, “they should perhaps consider wearing a garment such as a kilt when they present themselves at the polling place.” The following day, he added to his suggestion thusly: “Of course, any such kilt-like garment should be of decent length so as to protect the modesty of manhood and the sanctity of our electoral process. Any such garment should cover the ankles, most certainly.”

This suggestion spelled the end of the new law. “In order to prevent the intrusion into the voting booth of women dressed as men,” opined the Batesville Daily Guard, “we now require that men dress like women? Is this the majesty of the law about which we have heard so much?” Protests erupted, and most legislators who had supported the bill in question now publicly proclaimed their willingness to reverse course if but the governor would request a special session. Governor Hays did so, and on July 19, 1915, the Arkansas General Assembly held its shortest ever special session in order to remove the new voting requirements. As historian Michael Dougan has written, “The average Arkansas man, realizing that his political masculinity would now be tied to a sartorial femininity, quickly embraced the progressive vision of female political equality, if grudgingly. The question of ‘Who wears the pants around here?’ has never been answered in a less metaphorical manner.”

The national embarrassment over the breeches panic, however, may have facilitated the speed with which women’s suffrage was attained in Arkansas. Charles Hillman Brough, elected governor in 1916, sought to raise the state’s reputation through a variety of means, including promoting suffrage for women. In 1917, he signed into law a bill granting women the right to vote in party primary elections, and Arkansas women cast their first votes the following year. In 1919, he not only endorsed national suffrage for women but called a special session to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment once it passed, making Arkansas the twelfth state in the nation to do so.

For additional information:

Dougan, Michael. “Such a Drag: The Breeches Panic and Anti-Feminism in Arkansas in the Early Twentieth Century.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Spring 2020): 1–27.

Manne, Sheila. And No One Overreacted Ever Again: Moral Panics in the New South, 1900–1929. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Penix, M. O. A Stand-Up Guy (or The Hard Truth): The Autobiography of M. O. Penix. Little Rock: Democrat Printing and Lithography Company, 1922.

“The Political Cockburn.” Program for the retirement celebration of C. T. Cockburn. On file at Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Wade, Hilda. Suff-RAGE! Women Fighting Reactionary Politics. New York: Feminist Press, 1983.

Dr. Euphrenia Sibyl Simons-Cross

Arkansas Women’s Suffrage Centennial Committee

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.