calsfoundation@cals.org

Thomas D. W. Yonley (1827–1888)

Thomas D. W. Yonley was born in what was then Virginia (later to become West Virginia), became a lawyer, migrated to Arkansas as the South began to secede from the Union, left the state to become a Federal soldier, and then returned to Little Rock (Pulaski County) for a ten-year political career that took him to high offices and a critical role in the turbulent era of Reconstruction. He was elected to the convention that wrote the Reconstruction constitution of 1864, and then was elected chancery judge in Little Rock, attorney general of Arkansas, and chief justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court. As chief justice, he was the author of one of the pivotal decisions in Arkansas history. In the case of Rison et al. v. Farr, Justice Yonley’s elegant opinion overturned a statute enacted by his Republican allies in the Arkansas General Assembly that denied most Confederate soldiers the right to vote. But that bit of charity to the men who had fought against the country contributed to a harsh retribution from the federal government, which imposed martial law on Arkansas and other Southern states for several years.

Thomas Daniel Webster Yonley was born in 1827 in Hampshire County, Virginia, to Thomas D. W. Yonley Sr. and Rebecca Lupton Yonley. The region was part of Virginia, but when the Civil War broke out, people in the western, mountainous region of the state opposed secession, and in 1863 Congress and President Abraham Lincoln granted statehood to West Virginia. Little is known about Yonley’s early life or legal training, but he apparently spent some time in Kentucky. In September 1857, at Omaha, Nebraska, he married a woman from Kentucky, and two years later they moved to Little Rock. Margaret Ann LeSuer, or “Maggie” Yonley as she became known in Little Rock, was described by an Arkansas biographer as “a fine elocutionist,” a student of Shakespeare, and highly admired in Little Rock’s social circles in the nearly two decades the couple lived in Arkansas. They had two sons.

Yonley established a law practice, and when the great conflagration over slavery and secession approached, he seems to have been deeply divided, his heart on one side and his soul on the other. Briefly, starting in 1864, he published a newspaper called The Unconditional Union, which was later picked up by another unionist, Lieutenant Governor Calvin C. Bliss, and printed again for a time until 1866, when his plant was torched while he was in Washington DC on state business. (The Arkansas Constitution of 1864 created the office of lieutenant governor, which lasted for ten years until it was eliminated in the Constitution of 1874.)

After the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln, Yonley, like his native West Virginians, soon opposed secession by his new state and traveled to Missouri, where he supposedly joined the Federal army, although little is known about his actual service on either side. He is not listed in Civil War databases for the Union or Confederacy, although in the summer of 1862 one “T. D. W. Yonley” was listed as a private in a Confederate company at Little Rock called the Little Rock Provost Guard, which was made up of people up to forty-five years old who were not subject to conscription but who were to serve as a “special police” force for the capital city. After Federal troops took control of Little Rock on September 10, 1863, Yonley resumed his legal practice at Little Rock.

Areas of Arkansas under Federal control chose delegates to a convention to write a new constitution in 1864, and Yonley was one of the prevalent voices in composing the new charter, which formally emancipated slaves but without specifying their rights. It also paved the way for former Confederates to regain citizenship and full voting rights quickly. The charter was ratified in early 1864, but, nevertheless, the new Republican legislature passed a law on May 31 that curtailed voting rights for anyone who had not formally renounced the Confederacy by April 18, six weeks earlier. More than a year later, in 1865, after the act’s amnesty cutoff date, a Confederate prisoner of war had taken the oath to the Union and had been pardoned by President Andrew Johnson but was denied the vote, along with many other ex-Confederates, in a Congressional election happening that fall; this changed the election outcome.

The election decision was appealed to the Supreme Court and heard by Chief Justice Yonley and C. A. Harper, both of whom had been elected in 1864 by the votes of Unionists. Yonley’s eloquent opinion declared the obvious, that the legislature could not pass a law that clearly violated the constitution. Like the original constitution of 1836, the 1864 charter, which he had helped write, gave white men the right to vote, and the legislature could impose no restrictions.

“The constitution,” he wrote, “is the fortification within which the people have entrenched themselves for the preservation of their rights and privileges, and every act of the legislature, or other department of government, which infringes upon any right declared in the constitution, whether it be inherent in the people or created by that instrument, is absolutely void.” Yonley’s opinion waxed at length upon the inviolate nature of a constitution in America, as well as upon the certain power of judicial review.

While he was a Unionist and a Republican, Yonley believed that individual rights were superior to politics and had to be applied even to those who had betrayed the country by fighting for the Confederacy. He had previously defended David O. Dodd, who was hanged for spying for the Confederacy.

The ruling in Rison v. Farr prepared the way for Democrats and ex-Confederates to return to power. Historian Michael Dougan observed that, had the Unionists remained in power and ratified the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, as Tennessee had, Arkansas might have escaped the Radical Reconstruction that followed. Following Yonley’s decision and the restoration of ex-Confederate voting, Congress impeached President Andrew Johnson and ended Confederate voting until the ratification of the Arkansas Constitution of 1874.

Yonley’s opinion in Rison v. Farr was cited by the Arkansas Supreme Court in 2014 (Martin v. Kohls), when it struck down an act by the legislature barring people from voting if they did not have an official photo identification to prove they were who they said they were. The rationale was the same as Yonley’s—that legislators could not impair the right to vote guaranteed by the Arkansas Constitution.

Yonley and Harper rendered only five decisions. Both stepped down in 1866 and returned to private law practices. Yonley became chancery judge for Pulaski County but resigned in 1872 to run for attorney general successfully on the Republican ticket with Elisha Baxter, the new governor. He was attorney general for only two years, then stepped down and again practiced law.

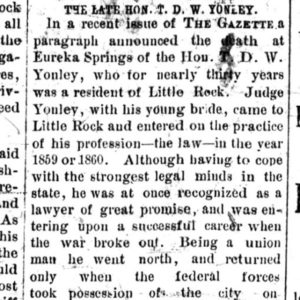

When the disputed presidential election of 1876 brought an end to Reconstruction and the gradual restoration of white control of government and society, the Yonleys and their sons moved to Denver, Colorado, where Yonley became part of the city’s leading law firm. Maggie Yonley revisited Arkansas in 1887 and died immediately upon returning to Denver. In poor health himself, Yonley traveled to Eureka Springs (Carroll County) the next year to test the healing power of the hot mineral springs that had become an attraction. He died there on June 1, 1888. He is buried alongside his wife in Denver.

For additional information:

Hempstead, Fay. A Pictorial History of Arkansas: From Earliest Times to the Year 1890. St. Louis: N. D. Thompson Publishing Company, 1890.

“The Late Hon. T. D. W. Yonley.” Arkansas Gazette, June 12, 1888, p. 4.

Rison et al. v. Farr, 24 Ark. 161, 1865.

Staples, Thomas S. Reconstruction in Arkansas, 1862–1874. New York: Columbia University Press, 1923.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Law

Law Thomas D. W. Yonley Death Announcement

Thomas D. W. Yonley Death Announcement

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.