calsfoundation@cals.org

El Dorado (Union County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 33°12’41″N 092°39’39″W |

| Elevation: | 272 feet |

| Area: | 16.20 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 17,756 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | May 5, 1870 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

443 |

455 |

1,069 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

4,202 |

3,887 |

16,421 |

15,858 |

23,076 |

25,292 |

25,283 |

25,270 |

23,146 |

21,530 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18,884 |

17,756 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

El Dorado is the county seat of Union County in south central Arkansas and a center for oil production and refining. Called once by boosters the “Queen City of South Arkansas” and, more recently, “Arkansas’s Original Boomtown,” the city was the heart of the 1920s oil boom in South Arkansas.

Early Statehood through the Gilded Age

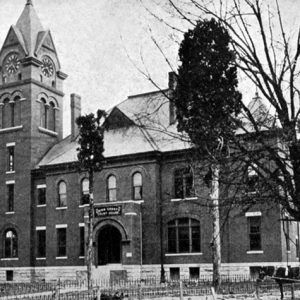

The city was founded in 1843 when Matthew Rainey set up a retail store in the area. Some reports state that Rainey had become stranded and sold his belongings to tide him over. So impressed with the sales to local settlers, he decided to stay permanently and named the site El Dorado, most often translated as “the Gilded Road” in Spanish. In 1843, El Dorado became the county seat for Union County. First Presbyterian Church, the oldest Presbyterian church in the region, was organized in El Dorado in 1846, with the First Baptist Church organized in 1845. El Dorado Female Institute, which was associated with the Presbyterian church, began operations that same decade.

By the 1850s, the area had become home to a number of cotton farms and plantations manned by numerous slaves. During the Civil War, Confederate units organized and trained in Union County. In 1864, Confederate units moved through the El Dorado area in order to engage advancing Union troops in the Camden (Ouachita County) area, but El Dorado itself saw no major military action during the conflict.

The community remained an isolated farming community from its founding until the late nineteenth century. The arrival of railroads by the late 1800s allowed business interests to exploit the native resources and build a thriving lumber industry. In 1883, a young man named Albert Williams was lynched in El Dorado.

Early Twentieth Century through Modern Era

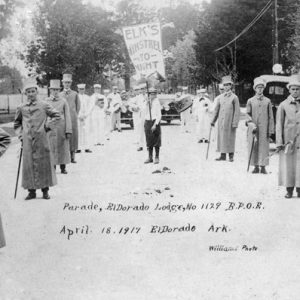

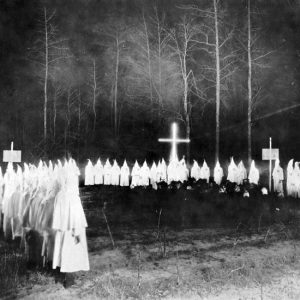

In 1902, the Tucker-Parnell Feud erupted over a series of disputes between the city’s marshal, Guy Tucker, and local businessman Tom Parnell. A gunfight in the city’s streets left two men dead and Tucker and others injured. Numerous other incidents would erupt over the following years in the area, leaving members of the Tucker and Parnell families and their allies dead. The year 1910 saw violence again during a race riot that reportedly entailed damaging businesses run by African Americans.

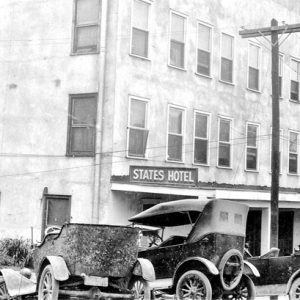

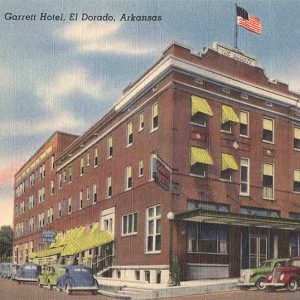

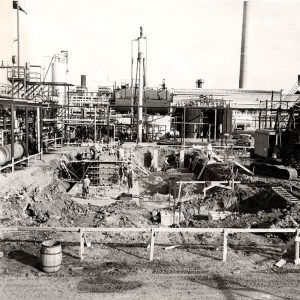

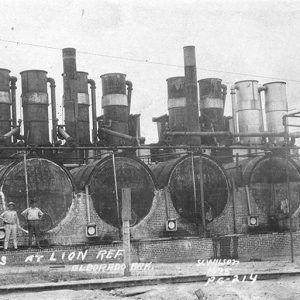

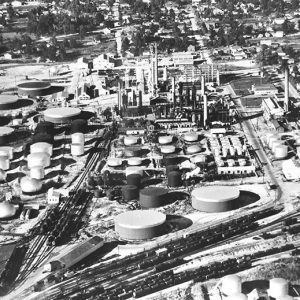

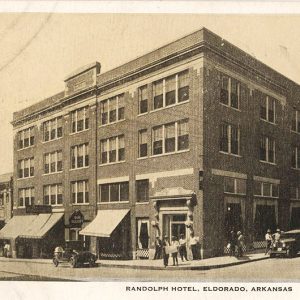

Economically, the community remained dependent on agriculture and lumber into the 1920s, limiting its growth. January 10, 1921, changed El Dorado forever with the completion of the Busey No. 1 well. Dr. Samuel T. Busey, a physician and oil speculator, completed the drilling of a well one mile southwest of El Dorado. The “discovery well” touched off a wave of speculators into the area, seeking fame and fortune from oil. The Busey No. 1 well would produce oil for only forty-five days, but El Dorado changed from an isolated agricultural city of approximately 4,000 residents to the oil capital of Arkansas. By 1923, El Dorado boasted fifty-nine oil contracting companies, thirteen oil distributors and refiners, and twenty-two oil production companies. The city was flooded with so many people that no bed space was available for them, leading to whole neighborhoods of tents and hastily constructed shacks to be erected throughout the city. The city’s population reached a high of nearly 30,000 in 1925 during the boom before dropping to 16,241 by 1930 and rising to 25,000 by 1960. Oil production, after plummeting by the early 1930s, recovered later in the decade.

During World War II, the city was the site of several chemical and munitions plants, most of which closed shortly after the war. The oil industry began to decline again by the late 1960s, causing a devastating impact on the economy of El Dorado.

In the early 1990s, a company called Information Galore based out of El Dorado brought public internet access to Arkansas for the first time.

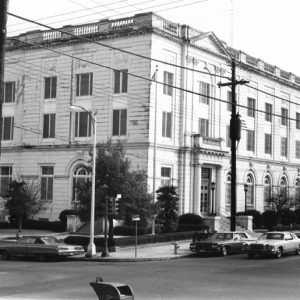

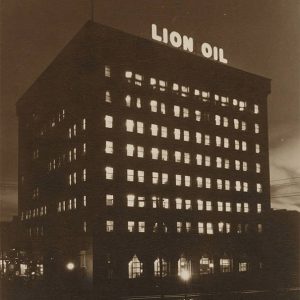

In 2004, the downtown area was declared a national historic district. Oil, chemical, and timber interests continue to play a powerful role in the local economy. El Dorado Chemical, Lion Oil, and Murphy Oil are among the corporations based in the city.

In the 2000 U.S. Census, the city had a population of 21,530. However, by 2010, the population had dropped to under 19,000, a number which included 9,417 black residents and 8,522 white residents. Worried about the population loss, local business and civic leaders began considering a variety of ways to revitalize the town.

In 2017, the Murphy Arts District (MAD) hosted the grand opening of the first phase of its $100 million renovation project. MAD comprises six venues spread over three city blocks. Phase one of the project included an 8,000-capacity outdoor amphitheater, a two-acre playscape, the farm-to-table Griffin Restaurant, and a 2,000-seat music hall with a four-story stage house. The restaurant and music hall are both housed in the historic Griffin Auto Company Building. Phase two involves the revival of the 1920s-era Rialto Theater for plays and music events, the opening of an art gallery, the repaving of downtown areas, and more for the purpose of making El Dorado a regional destination for the arts.

Education

From 1928 to 1942, El Dorado had a junior college in operation. Education facilities now include two private, sectarian primary schools (grades K–12) and the public El Dorado School District. El Dorado public schools have 4,500 students enrolled in its ten campuses and employs more than 360 teachers and administrators. Six elementary schools (five of which are divided into specialty campuses concentrating on special skills in addition to the standard curriculum), two intermediate schools, one alternative high school, and El Dorado High School comprise the district’s campuses. The city also has one community college, South Arkansas Community College. The college offers programs in the liberal arts, business, allied health fields, and skilled trades; it has an enrollment of over 1,350 students.

El Dorado education made national news in 2007 when Murphy Oil announced that it was donating $50 million in scholarships for the “El Dorado Promise,” a program guaranteeing to pay for college tuition for all El Dorado High School graduates who have been in El Dorado schools continuously since the ninth grade, up to 100% of tuition expenses for students attending El Dorado schools since kindergarten. In the first year of the El Dorado Promise, the rate of local high school graduates attending college jumped from sixty percent to eighty percent.

Attractions

Festivals and activities include the “Showdown at Sunset.” This event, held every Saturday evening during the summer since the 1980s, re-enacts the notorious 1902 shootout in the downtown area that led to a bitter feud between the Tucker and Parnell families. The Mayhaw Festival, held in early May, includes competitions in making jellies from the native mayhaw berry. MusicFest, held the first weekend in October since 1987, provides live music acts from country and rock artists. The SouthArk Outdoor Expo is held in early September on the campus of South Arkansas Community College and features demonstrations, workshops, and seminars on hunting, camping, and the outdoors as well as exhibits of outdoor products.

The South Arkansas Arts Center is host to numerous plays, public festivities, and art exhibitions. The historic John Newton House, built in 1849, and the South Arkansas Museum of African-American History are two popular historic attractions. Barton Library, a public library, boasts 69,000 items in its holdings. The South Arkansas Arboretum, a state park established in 1965, provides thirteen acres of natural fauna and walking trails within the city limits. In addition, the Arkansas Oil and Gas Commission currently has an office located in the city. The Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources is located in nearby Smackover (Union County).

Approximately ninety-five churches are organized within the city. Most churches in El Dorado are Baptist, but many other denominations are represented, including Methodist, Episcopal, Presbyterian, African Methodist Episcopal, Church of Christ, Pentecostal, Christian (Disciples of Christ), Roman Catholic, Church of God, Church of God in Christ, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Mennonite, and the Salvation Army.

Notable Figures

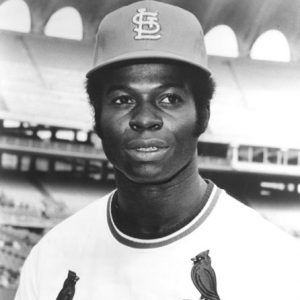

El Dorado has connections to a wide variety of prominent people, including: oil industry businessmen O. C. Bailey, Thomas Barton, and Charles H. Murphy Jr.; politicians Bruce Bennett and Gressie Carnes; athletes Lou Brock, Schoolboy Rowe, and Goose Tatum; Miss America Donna Whitworth; photographer Thase Daniel; public health and medical education pioneer Morgan Smith; writers Anna Nash Yarbrough and Charles Portis; musician Fern Jones; philanthropist and environmentalist Thomas Chipman McRae IV; journalist Ernie Dumas; businessman and sports promoter Lamar Hunt; and photographer and musician Richard Leo Johnson. Medal of Honor recipient John L. Canley spent most of his childhood in El Dorado.

For additional information:

Arnold, George. Gunfight on the Courthouse Square: The True Story of the Tucker-Parnell Feud in Union County, Arkansas, 1902–1905. El Dorado, AR: News-Times Publishing Co., 1995.

Benson, Joanna. “The Artistic Rebirth of Hell Dorado.” The Bitter Southerner, February 18, 2020. https://bittersoutherner.com/the-artistic-rebirth-of-hell-dorado-el-dorado-arkansas (accessed December 9, 2024).

Buckalew A. R., and R. B. Buckalew. “The Discovery of Oil in South Arkansas, 1920-1924.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 33 (Autumn 1974): 195–234.

Cordell, Ann Harmon. “El Dorado: ‘Place of Riches.’” Arkansas State Magazine, Spring 1967, pp. 32–37.

Crawford, M. Angela. “Portrait of a Pioneer Family: The Lacys of Union County.” South Arkansas Historical Journal 4 (Fall 2004): 21–27.

El Dorado, Arkansas. http://goeldorado.com/ (accessed May 28, 2022).

Gray, LaGuana. “‘Arkansas’s First Boomtown’: El Dorado and the Emergence of the Poultry Processing Industry.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Autumn 2013): 197–221.

———. We Just Keep Running the Line: Black Southern Women and the Poultry Processing Industry. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014.

Kent, Carolyn. “Uncle Sam Needs Your Resources: A History of the Ozark Ordnance Works.” South Arkansas Historical Journal 5 (Fall 2005): 4–20.

Ragsdale, John G. “Oil Development in South Arkansas.” South Arkansas Historical Journal 3 (Fall 2003): 18–24.

Roberts, Jeannie. “Arts-District Debut This Week.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 24, 2017, pp. 1A, 12A.

Kenneth Bridges

South Arkansas Community College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.