calsfoundation@cals.org

Richard Leon Mays (1943–)

Richard Leon Mays was an early civil rights attorney during the struggles to integrate public facilities and end bias in Arkansas courts and law enforcement. He was in the first group of African Americans to be elected to the Arkansas General Assembly in the twentieth century and became the second African American to be a justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court. Governor Bill Clinton appointed him to the court in 1979. He was inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame in 2016.

Richard L. Mays was born on August 5, 1943, in Little Rock (Pulaski County), the younger of two sons of Barnett G. Mays and Dorothy Mae Greenlee Mays. Although the family lived in an integrated neighborhood on the southeastern edge of Little Rock, his father operated a restaurant and a liquor store in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) and developed and managed real estate there. Mays occasionally worked in his father’s café while he was in high school and summers while he was a student at Howard University in Washington DC.

He attended Little Rock’s still-segregated schools, though he spent the third grade in integrated classes at Tucson, Arizona, where his mother was being treated for tuberculosis. He graduated from Horace Mann High School in 1961 with Mahlon Martin—who would become the first black city manager of Little Rock, director of the state Department of Finance and Administration, and head of the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation—and Henry Jones, who would become U.S. magistrate for the Eastern District of Arkansas.

Mays received a bachelor’s degree at Howard University in 1965. He was the only African American in his law school class at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) that fall, and in 1968 became the first black law graduate in over ten years. Mays would say many years later that he faced little discrimination in the law school, although a landlord who contracted with the university to provide housing tried to deny him an apartment after learning that he was black, saying he did not want his building bombed. After his first year of law school, he married Jennifer Winstead, who had been his high school girlfriend.

The U.S. Justice Department hired Mays as a trial attorney in the organized-crime section after law school in 1968. A year later, he returned to Little Rock as a deputy prosecutor under Prosecuting Attorney Richard B. Adkisson, who later was elected chief justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court. Mays was the Sixth Judicial District’s first full-time black prosecutor—and perhaps the first in the state.

Mays would recall his first of many early experiences in a racially discriminatory judicial system. He was prosecuting a black man who was accused of a felony in the court of Circuit Judge William J. Kirby and who was represented by a white lawyer. The defense lawyer, standing beside his client, told Kirby, “Judge, this is a good nigger,” and held up two fingers behind the man’s head, suggesting that this was how many years in prison he expected his client to get. “Judge, I object,” Mays said. “He’s using a disparaging term in reference to his client.” Kirby asked what the lawyer had said. “Judge, he said ‘nigger.’” The judge then said to the white lawyer: “Don’t you know how to say ‘nigra’?” The lawyer said he did. “Well, I guess that’s better than ‘nigger,’ Judge,” Mays said.

Mays was an intern for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. One of his first cases was a federal suit against the Arlington Hotel in Hot Springs (Garland County) for discriminating against black employees under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Black employees were always porters, but white employees were always bellhops, who received higher pay. Judge Oren Harris ruled against Mays, but the Eighth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the order and ruled for the black workers.

In 1971, Mays joined the state’s first racially integrated law firm, which was headed by John W. Walker, a stalwart civil rights lawyer who filed scores of civil rights suits in the second part of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first.

Another class-action lawsuit (Phillips, et al. v. Weeks, et al.), filed in 1972, alleged that Little Rock police engaged in a systematic pattern of brutality against blacks, who often were arrested, held for days on “suspicion” without charges being filed against them, and subjected to physical abuse. The trial lasted more than a month, but Judge G. Thomas Eisele did not rule for twelve years, by which time most of the practices had ended under a new police chief. Still, the judge granted some relief from the remaining practices.

When Mays went to Arkadelphia (Clark County) in 1972 to represent African-American high school students who were arrested following a major disturbance at Arkadelphia High School, the judge fined him for contempt of court for continuing to ask witnesses the race of people they were talking about. When another lawyer from the firm arrived to help Mays, the judge barred all members of the Walker law firm from ever practicing in Clark County. Oscar Fendler, a Blytheville (Mississippi County) lawyer, represented Mays and the other lawyers in an appeal to the state Supreme Court, which said the judge acted unconstitutionally and set aside his order.

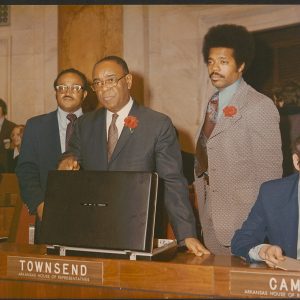

After the state reapportioned seats in the legislature in 1972 to equalize representation and give a voice to African Americans, Mays and three other African Americans were elected to the Senate or House of Representatives, the first black lawmakers since 1893. His first bill, which required common carriers to have uninsured motorist coverage, was blocked by House members when, by agreement with the speaker of the House, he brought it up during the morning hour, which was reserved for noncontroversial bills that required no debate. “Mays can’t have a noncontroversial bill,” Representative Paul Van Dalsem of Perryville (Perry County) protested to the House. It was explained to Mays that he could get bills passed if everyone was assured they had nothing to do with race. The legislature passed his common-carrier bill, but his bill creating a state civil rights commission never passed the House.

Seeing no real political future, he quit after three terms to devote himself to his law practice and businesses, including a chain of fast-food restaurants. In December 1979, Governor Bill Clinton appointed Mays to succeed the retiring Justice Conley Byrd on the Arkansas Supreme Court. He served on the court for a year. Mays was the second black justice after George Howard Jr., who was appointed to finish a term in 1977.

The biggest case the court addressed that year was a challenge to a business installment debt, which ended with the Supreme Court declaring that service charges that businesses typically included in installment loans should be counted as interest. It meant that all such loans were usurious if the interest and service charges exceeded the state constitution’s ten-percent limit on interest on any debt. The suit (Superior Improvement Co. v. Mastic Corporation) was decided four to three. Mays joined the dissenters. The decision panicked merchants and lending institutions, and the legislature referred to the voters in 1982 a constitutional amendment lifting the ten-percent ceiling. Voters ratified the amendment.

After his term on the court ended in January 1981, Mays returned to his private law practice and business interests. His political activities did not wane. He supported three successive governors, Clinton, Jim Guy Tucker, and Mike Huckabee, the latter a Republican. He served on a number of major state commissions: the Arkansas Ethics Commission (created by an initiated act in 1988), the Arkansas Economic Development Commission, the Arkansas Governor’s Mansion Commission, the state Bank Board, and the Claims Commission.

Mays worked full time for Bill Clinton in his 1992 campaign for president, raising more than a million dollars. He joined a lobbying and business-development firm in Washington DC for the eight years of the Clinton administration. He also did extensive business development in Africa.

His first wife died of cancer in 2000. In 2012, he married Supha Xayprasith, who was born in Thailand. His son and daughter became partners in his law firm.

For additional information:

“Interview with Justice Richard L. Mays.” Arkansas Supreme Court Project. Arkansas Supreme Court Historical Society. https://www.arcourts.gov/sites/default/files/oralhistories/Richard%20Mays%20Interview.pdf (accessed September 3, 2020).

Williams, Helaine R. “Richard Leon Mays Sr.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 3, 2018, pp. 1D, 5D.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.