calsfoundation@cals.org

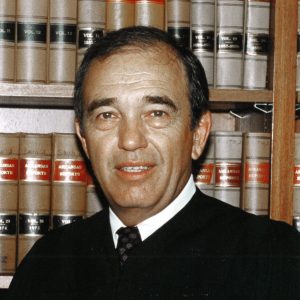

Donald Louis Corbin (1938–2016)

Donald Louis Corbin had a career as a state legislator and appellate judge spanning forty-four years. As a state representative, Corbin developed a reputation as a plainspoken maverick, and, as a judge, a reputation for pushing his colleagues to take unpopular stands, particularly on social issues. As his twenty-four-year career as a justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court was coming to an end in 2014, he had a bitter disagreement with other justices whom he thought had connived to avoid rendering a decision in the controversy over legalizing marriages of same-sex couples.

Donald L. Corbin was born on March 29, 1938, in Hot Springs (Garland County), where his father, Louis Emerson Corbin, was a meat-market manager for a Kroger grocery store; his mother, Mary Louise Sheffield Corbin, also did grocery work. He had one younger brother.

Corbin’s father joined the U.S. Navy in World War II and was sent to San Diego, California, where he was a butcher. His mother took her husband’s place at the Kroger meat market and then later followed her husband, with Donald, to San Diego, where she worked in grocery stores as a butcher for more than a year. After the war, the family returned to Arkansas, moving to Lewisville (Lafayette County) and then to nearby Texarkana (Miller County), where both parents worked for Kroger and Safeway stores. In Lewisville, his mother bought a café on the town square across the street from a café owned by his aunt.

In high school, Corbin became a member of the Future Farmers of America and was on a poultry-judging team that won district, state, and national championships; he won the gold medal for his judging in the national championship. He attended the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) but left to join the U.S. Marine Corps in 1959.

After leaving the marines, Corbin returned to Texarkana and began working for his mother at a collection agency. He met and married Loretta Icenhower, a Texarkana schoolteacher, and she encouraged him to return to the university. He graduated from UA in 1963 with a degree in history and sociology. He had decided he wanted to be a trial lawyer, so he went to law school there and received a law degree in 1966. He worked briefly as a lawyer at De Queen (Sevier County) before returning to Lewisville, where he had a practice in civil and criminal law. As his practice had far-ranging interests, he sued railroads for clients who were injured and defended railroads in other cases. His first political race was for city attorney of Lewisville, which he won. He would win every subsequent political race, six for municipal or legislative offices and five for appellate judgeships.

In 1970, friends persuaded him to run for a seat in the Arkansas House of Representatives. When Corbin, a Democrat, returned from filing at Little Rock (Pulaski County), he was dismayed to learn that he was running against a popular and indefatigable representative, also a Democrat, Gladys Martin Oglesby of nearby Stamps (Lafayette County). To his surprise, he won.

In the House of Representatives, he was a voice for the so-called country boys, lawmakers who represented rural areas and believed they were being shortchanged in the distribution of public services. He blocked an appropriation to convert programming on the Arkansas Educational Television Network from black and white to color, protesting that people in central Arkansas were getting color programming while outlying regions received no public television at all. The sponsor of the bill, Senator Guy H. “Mutt” Jones of Conway, pledged to deliver a statewide network at the next session if Corbin let his bill pass, and he did. Corbin also was a sponsor of an act for Governor Dale Bumpers that forgave student loans for new physicians who practiced in rural communities.

After ten years, Corbin did not seek reelection but instead ran for the seat from southwestern Arkansas on the new Arkansas Court of Appeals, which had been created two years earlier. He won easily. A month after joining the Court of Appeals, Corbin suffered a heart attack, and over the next twenty-four years, he underwent many surgeries and treatments for two types of cancer as well as heart, arterial, and gastric ailments; he rarely, however, missed a week of opinion writing. His first marriage ended in divorce as he left the legislature, and he married Dorcy Kyle of Hot Springs and Little Rock. They had five children.

Corbin served ten years on the court, the last four as chief judge, and was elected justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1990 to replace Justice John I. Purtle, who retired. Corbin served at total of three eight-year terms. During those twenty-four years, the court handed down an unusual number of groundbreaking and often unpopular decisions holding government actions (or inaction) to be in violation of the state constitution, with Corbin always in the majority and often the author of the opinions.

After voters ratified a constitutional amendment limiting the terms of legislators, constitutional officers, and members of Congress, the Supreme Court struck down sections of the amendment that limited the terms of members of Congress. Corbin, writing for the court’s majority, said it imposed a qualification for members of Congress beyond those established by the U.S. Constitution. The case later went to the U.S. Supreme Court as U.S. Term Limits v. Thornton.

In 1996, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld the convictions of three West Memphis (Crittenden County) teenagers for the murder of three boys whose bodies were found in a drainage ditch in 1993. One of the three was sentenced to death and the other two to life in prison. The case of the “West Memphis Three” became one of the biggest Arkansas criminal cases of the century and gained international notoriety. But in 2010, after police, prosecutorial, and jury misconduct surfaced, a key witness against the teens recanted her testimony, and the evidence became tainted, the Supreme Court unanimously ordered the trial court to conduct a new evidentiary hearing. Rather than face the prospect of a new trial, the state worked out an agreement with attorneys for the three men to plead guilty while claiming innocence and to be set free. In an oral history given in 2015 shortly after his retirement, Corbin grieved that he had played a role in affirming the convictions that caused the three men to spend so much of their lives in prison.

When Lake View School District No. 25 v. Huckabee, which challenged the constitutionality of the state’s operation and funding of the public schools, reached the Supreme Court for the fourth time in January 2004, Corbin rebuked legislators during the court’s oral arguments for failing to take steps to guarantee that all the state’s schools were providing a suitable and efficient education. “I don’t want to let anybody off the hook,” he told the government’s lawyers. “I want to stick the hook in real deep, so they’ll know at least one judge won’t put up with this again.” Legislators grumbled about the remark, and the speaker of the House of Representatives said the threat was out of line. But the legislature subsequently raised taxes, consolidated smaller schools, and passed a law requiring the funding of public education at an “adequate” level every year before the state distributed tax funds to the rest of the government.

The Supreme Court in 2014 unanimously struck down an act passed by the Republican-led legislature requiring voters to show a government-issued photo identification before voting. Majority-Republican legislatures were passing such laws in a number of states, and they were widely viewed as an effort to discourage voting by minorities. Corbin, who wrote the opinion, said the law added additional qualifications for voting and that the state constitution prohibited the legislature from doing that.

But the most contentious and controversial decisions of the era were four cases contesting state laws aimed at homosexuals. In all four, Corbin insisted that the equal-protection, due-process, and privacy provisions of the federal and state constitutions barred the state from discriminating against homosexual men and women. In 2002, the Supreme Court unanimously struck down the state’s sodomy law, which made homosexual activity a crime. As a legislator in 1977, Corbin had voted for the law, which required a $1,000 fine and up to a year in prison for committing a homosexual act. However, Corbin joined the unanimous decision (Jegley v. Picado, 2002) invalidating the law as a violation of privacy rights guaranteed by the state constitution. A year later, in Lawrence v. Texas, the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated such laws nationwide.

In 2006, Corbin wrote the Supreme Court’s ruling (Howard v. State) holding that the state’s Child Welfare Agency Review Board could not prevent same-sex couples from serving as foster parents. Two years later, an initiated act adopted by the state’s voters barred homosexual couples from serving as foster parents or from adopting children. The Arkansas Supreme Court, in Department of Human Services v. Cole (2011), also struck that law down, unanimously, on the same grounds, saying that such regulation did not reflect a correlation between the sexual orientation of parents and the safety of children.

The Pulaski County Circuit Court struck down a constitutional amendment outlawing same-sex unions, a case that reached the state Supreme Court in 2014. The court expedited hearing the case and decided, six to one, to affirm the lower court, but the court never handed down an opinion. Corbin sought to have the ruling released before leaving the bench (he was retiring at the end of the year) and offered his own opinion addressing the federal and state constitutional issues. Corbin retired effective December 31, 2014, and the decision was not handed down. With two new justices, the court delayed rendering a decision for another six months, until the U.S. Supreme Court struck down all such state laws in Obergefell v. Hodges, delivered on June 26, 2015. The Arkansas court then dismissed the Arkansas appeal as moot.

Corbin died on December 12, 2016, after a period of illness.

For additional information:

Blomely, Seth. “Lawmakers Say 2 Justices Crossed Line.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 4, 2004, p. 10A.

Bowden, Bill. “Long a State Justice, Corbin Dies at 78.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 14, 2016, pp. 1A, 7A.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Law

Law Politics and Government

Politics and Government Wright v. Arkansas

Wright v. Arkansas Donald L. Corbin

Donald L. Corbin

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.