calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas Traveler

A tune, a dialogue, and a painting from the mid-nineteenth century, the Arkansas Traveler became a catch-all phrase for almost anything or anyone from Arkansas: it has been the name of a kind of canoe, various newspapers, a racehorse, a baseball team, and more. The term is familiar to the present-day general public, especially as the name of a baseball team and a certificate presented to distinguished visitors to the state.

Origins

The Arkansas-based version of the Traveler is said to have begun in 1840. Colonel Sandford Faulkner got lost in rural Arkansas and asked for directions at a humble log home. Faulkner, a natural performer, turned the experience into an entertaining presentation for friends and acquaintances in which the Traveler was greeted by the Squatter at the log cabin with humorously evasive responses to his questions. Finally, the Traveler offered to play the second half, or “turn,” of the tune the Squatter was playing on his fiddle. The tune was the “Arkansas Traveler.” In his happiness at hearing the turn of the tune, the Squatter mustered all of the hospitality of his household for the benefit of the Traveler. When the Traveler again asked directions, the Squatter offered them but suggested that the Traveler would be lucky to make it back to the cottage “whar you kin cum and play on thara’r tune as long as you please.”

At approximately the same time Faulkner began performing the “Traveler,” a similar performance of the “Arkansas Traveler” tune and a related dialogue emerged outside the state. One cannot tell with certainty which version came first. According to Thomas Wilson, writing in Ohio History in 1900, customers were attracted to the Golden Fleece Tavern in Salem, Ohio, by performances of the “Traveller” before 1852. While the Arkansas-based version of the dialogue portrayed tensions based upon differences among people from Arkansas—such as urban versus rural or wealthy versus poor—most versions told the story from the Traveler-as-outsider perspective, taking an uncomplimentary view of the state. Mose Case, an albino African-American entertainer from Buffalo, New York, performed the Traveler and his version ended by declaring that the Traveler “has never had the courage to visit Arkansas since!” The Case version was published in 1863 and distributed widely.

The Tune

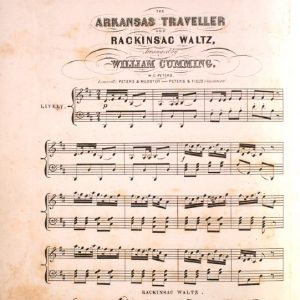

The sheet music to the tune was first published in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1847 as “The Arkansas Traveller and Rackinsac Waltz,” arranged by William Cumming. No one was credited with the composition. If not from the folk tradition, the tune was most likely written by Jose Tosso, a classical violinist and composer who lived in Cincinnati and was locally famous for his version of the “Arkansaw Traveler.” Several others, including Faulkner and Case, have also been credited with its composition. Over the years, the “Arkansas Traveler” has become one of the most recorded tunes in American history. The 1922 version by native-Arkansan “Eck” Robertson was among the first fifty recordings named to the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress, and the tune has appeared in jazz and symphonic arrangement, including a recording by the Boston Pops Orchestra.

The Painting

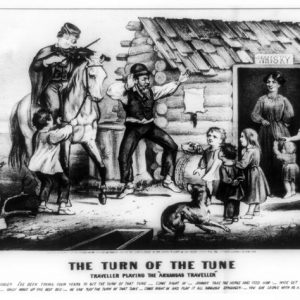

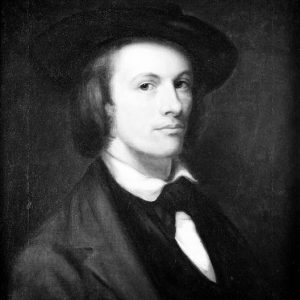

By 1856, Arkansas artist Edward Payson Washbourne had painted a picture illustrating the meeting between the Traveler and the Squatter, and in 1859, J. H. Bufford of Boston, Massachusetts, published the image for Washbourne as rendered by lithographer Leopold Grozelier. On the print, the “Arkansas Traveler” melody line appeared below “Designed by one of the natives and Dedicated to Col. S. C. Faulkner.” The text made it clear that Washbourne the artist, Faulkner the Traveler, and the Squatter were all from Arkansas. On Washbourne’s easel at the time of his death was a complementary picture, “The Turn of the Tune.”

In 1870, New York printmakers Currier & Ives brought out popular prints of the “Arkansas Traveller” and “The Turn of the Tune” with abbreviated dialogue, crediting neither Faulkner nor Washbourne. Thus, the prints supported the “outsider” version of the Traveler dialogue, leaving the Squatter and his household as the only sure representatives of Arkansas.

Traveler Stereotypes

In humorous performance and in popular print, the Traveler came to perpetuate a negative rural or “hillbilly” reputation for Arkansas. In 1877, a commentator in the Arkansas Gazette claimed that the Traveler evoked an image of “shiftlessness, indolence and improvidence.” Stereotypical jokes about the state appeared in the Arkansaw Traveler, a nationally distributed humor journal founded by Opie Read and published from 1882 to 1916. Arkansas’s association with its frontier past continued in Kit, The Arkansas Traveller, one of the most performed plays in nineteenth-century America. Well-known Broadway veteran Frank Chanfrau began acting in the title role in 1869, and after his death in 1884, son Henry Chanfrau kept Kit in regular performance around the United States until 1899. In 1896, William H. Edmunds, in a pamphlet titled “The Truth about Arkansas,” calculated that the Traveler image had cost the state “millions of dollars.” This cost took into consideration the presumed economic progress that would have taken place in Arkansas without the burden of a negative reputation. First published in 1903, the bestselling joke book in American history exploited this hillbilly image by using the state’s name in the title—Thomas Jackson’s On a Slow Train Through Arkansaw.

The Traveler in the Twentieth Century

Meanwhile, the term found itself as simply a name on riverboat, racehorse, newspaper, and newspaper column, as well as a nickname for any number of people from Arkansas. In 1901, the Little Rock Travelers minor league baseball team was established. The team became the Arkansas Travelers in 1961, the first professional league sports team in the country named for an entire state. Hazel Walker had named her all-star women’s professional basketball team the Arkansas Travelers in 1949. In another sports connection, Dutch Harrison, one of the greats of professional golf, carried the nickname Arkansas Traveler. In 1903, the Arkansaw Travelers Association was founded for white men in Arkansas of any occupation involving traveling, especially sales. A social and business organization offering death benefits to members, the Travelers passed from the scene by 1920. At mid-century, Arkansas Traveler boats, made in Little Rock (Pulaski County), gained popularity nationwide. In 1992 and 1996, Arkansas-based campaigners for Bill Clinton carried the name Arkansas Travelers all over the country, contributing significantly to Clinton’s election and re-election as president of the United States.

With people becoming less concerned about its effect on the state’s reputation, the Traveler in some of its old trappings lingered in Arkansas throughout the twentieth century. For example, well-dressed visitors to Hot Springs (Garland County) were photographed for Happy Hollow postcards, in front of rustic “Arkansaw Traveler” backdrops. “Arkansas Traveler” Bob Burns and the team of Lum and Abner (Chet Lauck and Norris Goff) achieved great success as radio and movie entertainers, basing their humor on the backwoods image of Arkansas. (Burns even starred in a 1938 movie titled The Arkansas Traveler, though it was neither filmed nor set in the state.) Beginning in 1968, the Arkansaw Traveller Folk Theater in Hardy (Sharp County) revived the music, story, and image of the Traveler.

In 1941, the Arkansas General Assembly created the Arkansas Traveler Certificate to honor out-of-state visitors, the first presentation going to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. These certificates continued the Traveler-as-outsider theme, placing visitors in the role of the Traveler, but by this time, the image had lost its power as a regional stereotype, and the certificate has become a regular attraction at gatherings where visitors are honored.

For additional information:

Brown, Sarah. “The Arkansas Traveller: Southwest Humor on Canvas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Winter 1987): 348–375.

Hancox, Louise. “Picturing a Nation Divided: Art, American Identity, and the Crisis over Slavery.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2018. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2768/ (accessed March 26, 2024).

———. “The Redemption of the Arkansas Traveler.” Ozark Historical Review 38 (Spring 2009): 1–30. Online at https://history.uark.edu/_resources/pdf/ozark-historical-review/ohr-2009-1.pdf (accessed March 26, 2024).

Hudgins, Mary D. “Arkansas Traveler—A Multi-Parented Wayfarer.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Summer 1971): 145–160.

Lankford, George. “The Arkansas Traveller: The Making of an Icon.” Mid-America Folklore 10 (1982) 16–23.

Masterson, James R. Arkansas Folklore. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1974.

Mercer, H. C. “On the Track of the Arkansas Traveller.” Century Magazine 5 (March 1896): 707–712.

Smith, Ophia D. “Joseph Tosso, The Arkansaw Traveler.” Ohio History 56 (January 1947): 16–43.

Thomas Wilson. “The Arkansas Traveller.” Ohio History 8 (January 1900): 296–308.

William B. Worthen

Historic Arkansas Museum

Arkansas Traveler Print

Arkansas Traveler Print  Arkansas Traveler by Edward Washbourne

Arkansas Traveler by Edward Washbourne  "Arkansas Traveler" Music

"Arkansas Traveler" Music  "Arkansas Traveler"

"Arkansas Traveler"  "Arkansas Traveler"

"Arkansas Traveler"  Arkansas Traveler Award

Arkansas Traveler Award  Arkansas Traveler Music

Arkansas Traveler Music  "Arkansaw Traveler"

"Arkansaw Traveler"  Edward Payson Washbourne

Edward Payson Washbourne

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.