calsfoundation@cals.org

Communist Party

The Arkansas Communist Party reached the peak of its influence between 1932 and 1940. Loosely affiliated at that time with the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA), the Arkansas branch became incrementally involved in programs of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU) and Commonwealth College, two organizations striving for improved working and living conditions among the state’s tenant farmers and sharecroppers. During its most active years, the party also sponsored candidates for local, state, and national offices.

The party formed between 1930 and 1932 from a remnant of members of Newllano Cooperative Colony who settled near Mena (Polk County). Arley Woodrow of Ink (Polk County) played a significant role in establishing the group. The party obtained and distributed communist literature, and it was publishing its own newsletter by 1939. In 1940, it produced a platform for the general election. This publishing work was ancillary to efforts to organize agricultural workers. In the 1930s, in Arkansas as elsewhere, Communist Party members were required to join unions and other organizations and then work from within to direct matters along communist lines. Consequently the party’s history in this decade is largely a record of key individuals working within progressive organizations to foster social change.

The STFU was formed in 1934 by sharecroppers and tenant farmers in eastern Arkansas. The Depression and New Deal crop reduction programs led to massive evictions from the land. White and black sharecroppers united to try to salvage their lives out of the economic chaos that surrounded them. By 1936, the STFU lobbied Washington DC to elevate awareness of the farmers’ plight, fought off planter repression, and organized a cotton choppers’ strike to raise wages for day laborers. The organization grew rapidly, but there was still a financial need to situate the group within a larger labor union network. Consequently, the STFU opted to align with the communist-led Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1937 and was interested in joining the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), a unit newly formed within the CIO. Though hopes were high that this move would benefit both the STFU and the UCAPAWA, the latter’s communist leader, Donald Henderson, held primary loyalties to the Communist Party and to the CIO. The alliance dissolved in 1939.

Commonwealth College near Mena gained a reputation as a training ground for future labor union leaders that included a strong indoctrination in socialist ideology. From 1935 to 1939, the school was associated with the STFU, which sent young farmers to Commonwealth on scholarships. Students and faculty at the college earned a national reputation for hands-on involvement with the Southern sharecroppers’ movement. Because of this reputation and the progressive nature of the work being carried out there, communists were also drawn to the college. By 1938, it was alleged that twenty of the twenty-five faculty members, as well as maintenance and administration workers, were members of the CPUSA or the Arkansas branch, along with students Bob Reed, Horace Bryan, and Ralph Field. Ideological differences emerged between the college and the STFU and between the current communist and former socialist administrations of the school. The effort to turn the college in a communist direction failed when the school closed in 1940.

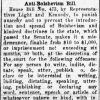

Despite these difficulties, the Arkansas Communist Party’s reputation grew to the point that it could begin sponsoring candidates for public office. Arley Woodrow was one of the most active office seekers in party history. He was state chairman of the party in 1940 and a candidate for presidential elector the same year. Prior to that, he ran for governor in 1932, for lieutenant governor in 1936, and for mayor of Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1939. Joining Woodrow in his run for office in 1940 was former Commonwealth College student Ralph Field, who ran for governor. Secretary of State C. G. Hall declined to put either man on the ballot, citing Act 33 of 1935, which prohibited groups seeking the overthrow of the U.S. government from appearing on Arkansas’s general election ballot.

Tired of fighting socialists seeking similar communitarian goals, the Arkansas Communist Party declined after 1940. Some communist leaders left Arkansas at that time to work on other communist projects, while others remained in the state but chose to retire from politics to follow other pursuits. The party never returned to its prior prominence. Following in step with similar movements across the nation, in 1951, the Arkansas General Assembly passed a restrictive measure known as Act 401. The act required members of organizations allegedly advocating the overthrow of the federal or state government to register with the Arkansas State Police. The registration was specially targeted at members of the Communist Party and its affiliates. Such persons were required to register within ninety days of passage of the law. Failure to do so could, upon conviction, result in a fine of $50,000 to $100,000 or a prison sentence of six months to two years. The 1975 free speech case of Cooper v. Henslee resulted in the overturning of an older state law outlawing the employment of communists by any state agency or institution.

For additional information:

Arley Ray Woodrow Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Cobb, William H., and Donald Grubbs. “Arkansas’ Commonwealth College and the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 25 (Winter 1966): 293–311.

“Hall Seeking Ruling on Communists.” Northwest Arkansas Times, September 10, 1940, p. 1.

Newkirk, Anthony B. “‘A Delicate Matter’: The 1958 Special Education Committee Hearing.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 78 (Autumn 2019): 274–295.

Stan C. Weeber

McNeese State University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.