calsfoundation@cals.org

Virginia Gardner (1904–1992)

Virginia Gardner was a journalist and left-wing activist. At one time a member of the Communist Party, she was also the author of a well-received biography of Louise Bryant, the wife of Russian Revolution chronicler John Reed. Although born in Oklahoma, Gardner spent most of her youth in Arkansas.

Virginia Gardner was born on June 27, 1904, in Sallisaw, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). She was the youngest of three daughters born to Gertrude Boltswood Gardner and John Gardner, who was a banker. The family moved to Fort Smith (Sebastian County) when she was two. That same year, her father contracted tuberculosis. He was taken to Colorado for treatment, and he sometimes returned there in the summers. Gardner’s mother died when Gardner was ten. Her father married Caroline Klingensmith three and a half years later.

After getting her early education in Fort Smith, Gardner earned a BA in journalism from the University of Missouri in Columbia, graduating in 1924. Her first job was with the Pawhuska, Oklahoma, Daily Journal. She also did some freelance writing before moving on to the Kansas City Journal Post. Shortly afterward, Gardner returned to Fort Smith, taking a job with the Southwest Record. She moved to the St. Louis Times in 1927. She joined the Chicago Tribune in 1930.

Gardner married Jerry Butler, a socialist and fellow journalist, on December 17, 1927. They divorced, and she married newspaperman and leftist Marion “Red” Marberry in 1937. That marriage also ended in divorce in 1942.

In 1938, Gardner joined the Newspaper Guild in Chicago, Illinois. She became an official member of the Communist Party in 1939, the same year she filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) concerning her treatment at Chicago Tribune; in March 1940, she was dismissed from the paper. The firing was contested, and the NLRB ordered her rehired. However, demoted and prohibited from getting any bylines, she left the paper in 1940.

She then moved to New York City, where she worked with the Women’s Division of the Democratic National Committee. In 1941, she was elected a lifetime member of the Newspaper Guild. That same year, she served as executive secretary of the Citizens Committee for Harry Bridges (president of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union ILWU) in New York City. The committee had been formed in an effort to prevent his deportation.

In 1942, as the United States entered World War II, Gardner moved to Washington DC to begin work at Federated Press, a labor news service. She resigned later that year to take a job as the Washington correspondent for New Masses, a magazine long associated with the Communist Party. In 1947, she left the magazine and moved to Los Angeles, California, where she began working for the People’s World, the Communist Party’s West Coast paper.

Gardner’s longtime association with the Communist Party made her a target amidst the growing Red Scare, and she was subpoenaed to appear before the Tenney Committee, the California legislature’s version of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1948. Gardner continued to write, contributing articles to the Communist magazine Masses & Mainstream, in addition to her ongoing work with the People’s World. However, in 1951, Gardner was dismissed from the People’s World, and unable to find another newspaper job, she supported herself working in a meat-packing plant.

Hoping to find greater opportunities in the east, she drove to New York. Unable to find a journalism post, she was again forced to support herself by working in a meat-packing plant. In 1955, she got a job with the Daily Worker, where she reported on the trial of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, who were accused of selling nuclear secrets to the Russians. Her work was published as a book, The Rosenberg Story, by Masses & Mainstream. Gardner continued to write for the Communist Party–sponsored Daily Worker until December 1959, when she resigned. After spending the first half of 1960 on the staff of Factor, a monthly magazine covering issues related to psychiatry, Gardner worked as a freelance medical writer until the end of 1962. That same year, she formally left the Communist Party. She then took a position as an editorial assistant to socialist philosopher and activist Corliss Lamont, a post she would hold from 1963 to 1971.

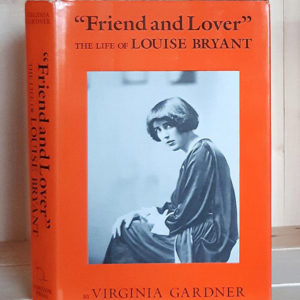

Gardner’s final professional effort was writing a biography of Louise Bryant, the wife of radical journalist John Reed. Gardner’s work, “Friend and Lover”: The Life of Louise Bryant, published in 1982, was well received, as reviewers applauded Gardner’s well-crafted and well-researched effort to move Bryant out from behind Reed’s shadow, establishing her as a historic figure in her own right. Following her book on Bryant, Gardner undertook the writing of a memoir of her long and eventful life. It was unfinished when she died in a San Diego, California, nursing home on January 5, 1992.

For additional information:

Gardner, Virginia. “Julius & Ethel: Researching the Rosenberg’s Story.” The National Committee to Reopen the Rosenberg Case. http://ncrrc.org/rosenbergs/julius-ethel/ (accessed November 17, 2020).

———. “Ruminations on a Long Life: An Autobiographical Transcript.” The Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. New York University, New York, New York. http://www.nyu.edu/library/bobst/research/tam/gardner_mss.html (accessed November 17, 2020).

Heise, Kenan. “Virginia Gardner, Former Tribune Reporter, Author.” Chicago Tribune, February 5, 1992. Online at http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1992-02-05/news/9201110375_1_miss-gardner-mother-cabrini-newspaper-guild (accessed November 17, 2020).

Virginia Gardner Papers. The Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. New York University, New York, New York. Guide online at http://dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/tamwag/tam_100/ (accessed November 17, 2020).

Richmond, Al. Review of Friend and Lover. Science & Society 47 (Fall 1983): 348–351.

William H. Pruden III

Ravenscroft School

Literature and Authors

Literature and Authors Mass Media

Mass Media Women

Women World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Friend and Lover

Friend and Lover

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.