calsfoundation@cals.org

Penal Systems

aka: Prisons

The penal system of Arkansas has been fraught with controversy through the years. It has been central to the careers of some of the state’s governors and has more than once drawn national and international attention for its faults and shortcomings.

Beginnings

Many of the Europeans who settled in the United States believed that the chief purpose of government was to punish sinners while leaving the righteous alone. As a result, many of the early actions of colonial and territorial Arkansas pertained to crime and punishment (as was the case across North America). Arkansas Post was a colonial settlement of the French and Spanish (mostly the French) during the seventeenth century; a prison was one of the first structures to be established at the post in 1731, when the French government began to treat it as a genuine military post. During the eighteenth century, however, the post commander was expected to provide local justice for smaller crimes and disputes, while dangerous criminals were to be removed south to New Orleans, Louisiana.

When Arkansas became part of the United States through the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, Arkansas Post continued for a time to be the center of government for the region, first as part of the Louisiana Territory, then as part of the Missouri Territory, and in 1819 as the capital of Arkansas Territory. The first jail built at the post under American jurisdiction was erected in 1813, and it was the only public building in the settlement for many years. After the center of territorial government moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Arkansas Post was demoted to the county seat of Arkansas County, a second jail was built in 1835 to serve as the county jail. Meanwhile, as other counties were created and as county seats were moved to new locations, courthouses and jails were among the first buildings to be erected in each county seat. Sometimes the two were incorporated into the same structure, as in Helena (Phillips County) in 1833. More often, the courthouse and jail were separate buildings built near each other, as was the case in Davidsonville (Randolph County) in 1816.

The punishment of criminals usually involved fines, whipping, branding, the stocks, or hanging, but a new approach to crime was being considered in cities such as Boston, Massachusetts; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and New York City, New York. This new approach advocated an attitude of rehabilitation rather than punishment of criminals. Those who favored this new approach defended it as more humane and more helpful to society as a whole. Opponents of this school of thought warned that the idea of punishment is easily defined and limited, while a promise of rehabilitation could justify harsher measures or longer sentences. This philosophic debate was not much discussed in Arkansas. James McVicar, third warden of the state prison in Arkansas, deliberately pursued the goal of rehabilitating criminals. Challenged by low budgets and by prisoner riots that badly damaged the facilities, McVicar eventually resigned his position and became involved in the California gold rush.

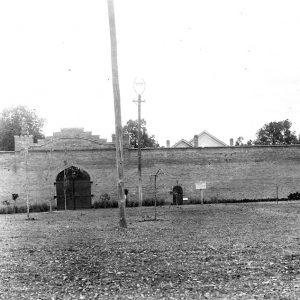

Even before Arkansas became a state, voices called for a central prison. Albert Pike wrote in the Arkansas Advocate of August 14, 1835, about the need for a prison for Arkansas. Creating such a structure was a priority to the early state government, which approved legislation creating a state prison in 1838. The next year, 92.41 forested acres were purchased roughly one mile west of Little Rock’s city limits, and construction began at the site. The first prisoner was not incarcerated there until 1842, and the prison was not complete until the following year. The prison was built to hold up to 300 inmates, and it included fortified guard towers at each of the four corners. While the state government had purchased the land and had paid for the construction of the prison, it did not intend to use state money to operate the prison. Instead, the prison was contracted to private parties who set the prisoners to work in construction and other forms of labor.

The Convict Lease System

This convict lease system was profitable to the state and to the investors who participated in the system, but it lent itself to abuse and neglect of the prisoners. In spite of the essential injustice of the system, it survived into the twentieth century as a basic feature of Arkansas’s penal system.

During these years, prisoner unrest frequently created problems for the administrators of the state’s prison. A fire in 1846, caused by a prisoner uprising, badly damaged the structure, but repairs were made by the prisoners over the following three years. In 1863, the prison was captured by Federal troops and remained a federal prison for the next four years. In 1873, the convict lease system that had existed unofficially was codified in state law. The lessees appointed by the state government were paid thirty-five cents a day for each prisoner to provide clothing and food for the inmates and were permitted to put prisoners to work; one of the jobs assigned to prisoners was erecting new buildings on the penitentiary grounds. Over the years, new laws refined the system from an administrative side, without making any kind of change in the lives of the prisoners. Attempts in the 1880s and 1890s to keep the state government in charge of state officials were undermined by the reality that convict leasing not only saved the state money but often provided additional income to Arkansas. Railroads, farms, mines, and other private enterprises all employed inmates of the state penitentiary. One of the most notorious cases of prisoner abuse occurred at Coal Hill (Johnson County), where prisoners were subject to beatings, long hours of work, and insufficient food and clothing. An investigative article in the Arkansas Gazette prompted public outcry, but the responses of state government tended to address particular abuses at Coal Hill rather than the problems embedded in the system.

Governors Jeff Davis and George Washington Donaghey both fought the convict lease system, but with different results. At the start of Davis’s first term as governor, the state penitentiary was torn down to make room for the new capitol building, which is still in use today. A new penitentiary was built five miles south of Little Rock. Many of the state’s prisoners were leased to the Arkansas Brick Manufacturing Company, while others were put to work on a prison farm at England (Lonoke County). Engaged in fierce debate with the state legislature over the politics and economics of the penal system in Arkansas, Davis chose to publicize the horrific conditions experienced by prisoners. In the end, he failed to bring about any changes in the system. A few years later, Governor Donaghey found himself battling the same conditions. At the end of his term, Donaghey pardoned 360 prisoners—between one third and one half of the prison population at the time—to call attention to the problems and to disrupt the system.

Meanwhile, Arkansas acquired more farmland for the prison system. The Cummins Plantation in Lincoln County had been purchased in 1902, and the Tucker Farm in Jefferson County was bought in 1916. Both facilities were principally cotton plantations. Black prisoners were sent to Cummins and white prisoners to Tucker. Since these farms were run by the state, they made it possible to eliminate the practice of leasing convicts to private farms and businesses.

Growth, Scandal, and Reform

While the state penitentiary in Little Rock was probably the most notorious penal system in Arkansas in the nineteenth century, it was not the only penal system in Arkansas. Fort Smith (Sebastian County) was home to the Federal Court of the Western District of Arkansas, which also handled cases from the Indian Territory to the west. Of the judges who served in Fort Smith, the most famous was Isaac Parker, the “Hanging Judge.” Parker’s efforts at reform are often overlooked because of the more sensational fact that he sentenced 160 condemned criminals to death during the twenty-one years he served as judge of the district. Also, counties continued to have their own jails, and some cities also built jails. Many of these were low-security facilities, such as the Johnson County Jail in Clarksville. Sidney Wallace escaped from that prison in 1873 by knocking out a window and jumping to the ground; later the same year, he was able to obtain a gun while in prison and shoot to death one of the witnesses who had testified against him; the witness was outside the jail in the town square at the time. As a result of events like these, condemned prisoners often were transferred from various county jails to the state penitentiary; those (like Wallace) condemned to death were then returned to the county jails a day or two before the scheduled execution.

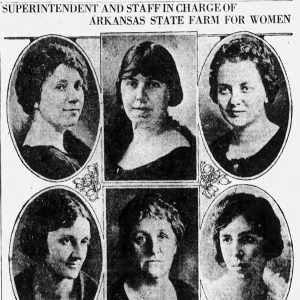

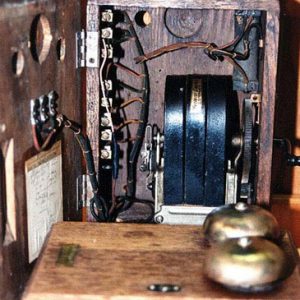

The end of the convict lease system in Arkansas did not guarantee an end to problems in the state prisons. More units were acquired during the early decades of the twentieth century, but the state government did not always supply these facilities with professional staff. Instead, the administrators of each facility often needed to appoint “trusties” selected from the group of prisoners to help run the prisons and even to maintain security. Ideally, this system might have led to more humane treatment of prisoners by their fellow prisoners, but the reality was the reverse. Prisoners were abused and tortured, often for petty misdemeanors. An investigation into the conditions at the Arkansas State Farm for Women, for example, found widespread sexual abuse of the prisoners by male guards and volunteers. Winthrop Rockefeller made prison reform part of his platform in his campaigns for governor in the 1960s. Evidence of mistreatment of prisoners, including the use of the infamous Tucker Telephone, opened the eyes of Arkansans to the need to fund prisons properly so that professional staff could be trained to maintain them. At times, the political process overwhelmed the reform-minded politicians, such as when Governor Rockefeller was forced to fire Superintendent Tom Murton, who had been hired to fix the problems in the Arkansas prison system. Murton’s zeal for reform had led him to exaggerate the problems in the system (which was not an easy accomplishment, given the severity of those problems) by claiming, for example, to have found graves of prisoners who had been beaten to death and secretly buried within the prison walls. Governor Rockefeller’s desire for reform was supported by the federal judiciary system when Judge J. Smith Henley declared the entire state prison system to be unconstitutional in 1969 in the Holt v. Sarver case. Corrections to the system required several years, but the system was ruled acceptable within the guidelines of the United States Constitution in 1982.

Among the changes to the prison system that occurred during and after those years were the construction of new prisons and expansion of older facilities, improved healthcare (including mental healthcare) for prisoners, educational facilities and work release programs, and additional opportunities for useful activities for prisoners. By 2009, seven Arkansas prisons were operating farms of various kinds, totaling more than 30,000 acres. Industrial programs for prisoners include making clothing, mattresses, and furniture; graphic arts; welding; vehicle refurbishing; silk screening; and engraving. In 1990, Arkansas opened its first “boot camp” for non-violent offenders, being a military-style prison intended to assist prisoners more directly to prepare to return to life after serving their sentence.

While some progress was being made in prison reform, the prison blood scandal at Cummins—in which corruption and poor supervision resulted in disease-tainted blood, often carrying hepatitis or HIV, knowingly being shipped to blood brokers, who in turn shipped it to Canada, Europe, and Asia—showed that reform had a long way to go.

Another public concern involving the Arkansas prison system is the privatization of prisons. Medical services were the first facet of prison life to be managed by privately owned providers. Beginning in 1998, the state system has included privately managed prisons in an attempt to control costs. Meanwhile, in a reversal of nineteenth-century trends, the Arkansas prison system has been forced to use various county jails as overflow housing for state prisoners. In 2024, the state bought an 815-acre property in Charleston (Franklin County) for the construction of a new 3,000-bed facility. Arkansas’s only federal prison opened in Forrest City (St. Francis County) in 1998 this prison contains two units: one low-security unit and one medium-security unit.

Death Penalty

From territorial times until the present, the government of Arkansas has reserved the death penalty as punishment for the most severe crimes, with the exception of about a decade in the 1960s and 1970s. Hanging was the usual form of execution in Arkansas until 1913, when the state legislature acted to replace hanging with electrocution and funded a room equipped for such executions at the state penitentiary in Little Rock. In 1964, the Arkansas Supreme Court declared the death penalty unconstitutional, but it reversed that decision in 1973. A complex pattern of appeals frequently delays executions for years after convictions, however, and the first execution in Arkansas following the 1973 decision did not take place until 1990. Lethal injection has replaced electrocution as a form of execution in Arkansas.

Conclusion

Early forms of the penal system in Arkansas were designed to rehabilitate criminals at a minimal cost to the state. These efforts to save money frequently resulted in brutal mistreatment of those imprisoned. Since the prison reform of the 1960s and 1970s, concern has continued to be expressed that state government is spending a great deal of money housing and caring for convicted criminals. As the prison population has grown, more prisons meeting acceptable standards have been required. Efforts to reduce the prison population have included reducing sentences and releasing prisoners early, usually rewarding those who have exhibited good behavior during their time in prison. A similar controversy has been generated by the pardoning of criminals by Arkansas governors, especially Governor Mike Huckabee. Questions were raised during his campaign for the Republican presidential nomination in 2008 about the pardons he had granted as governor.

For additional information:

Barnard, Lewis. “Old Arkansas State Penitentiary.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 13 (Autumn 1954): 321–323.

Bayliss, Garland E. “The Arkansas State Penitentiary Under Democratic Control, 1874–1896.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 34 (Autumn 1975): 195–213.

Crosley, Clyde. Unfolding Misconceptions: The Arkansas State Penitentiary, 1836–1986. Arlington, TX: Liberal Arts Press, 1986.

Ellis, Dale. “State Ranked No. 3 for Incarceration Rate.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 30, 2024, pp. 1A, 2A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/dec/29/advocacy-group-says-protect-arkansas-law/ (accessed December 30, 2024).

Ferkenhoff, Eric. “Starved to Death in an American Jail, the Man Who Couldn’t Pay $100 Bail.” Newsweek, January 13, 2023. https://www.newsweek.com/2023/01/20/starved-death-american-jail-man-who-couldnt-pay-100-bail-1773459.html (accessed January 17, 2023).

Flock, Elizabeth. “What’s the Matter with Arkansas? Prison and Jail Lawsuits Signal Trouble.” Al Jazeera America, October 14, 2015. http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2015/10/14/whats-the-matter-with-arkansas.html (accessed March 29, 2022).

Gill, Lauren. “The Prison Next Door.” Bolts Magazine, September 11, 2025. https://boltsmag.org/arkansas-prison-franklin-county/ (accessed September 12, 2025).

Haman. John. “$27.25 a Day and All the Soybeans You Can Reap.” Arkansas Times, May 10, 1996, pp. 11–13.

Hawkins, Van, ed. Cries from the Walls: Hell in Arkansas Prisons. Jonesboro, AR: Writers Bloc, 2024.

Jackson, Bruce. Inside the Wire: Photographs from Texas and Arkansas Prisons. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013.

———. “Texas Death Row and the Cummins Prison Farm in Arkansas.” Southern Cultures 13 (Summer 2007): 112–129.

Laura Cornelius Conner Papers. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Ledbetter, Calvin R., Jr. “The Long Struggle to End Convict Leasing in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 52 (Spring 1993): 1–27.

Mast, Lindsay. “Barred from Every Angle: Ninety Days to Save Your Life from Arkansas Prisons.” Arkansas Law Review 77 (February 2025): 807–841. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/alr/vol77/iss4/6/ (accessed March 7, 2025).

Miller, Jennifer Marie. “Sentencing Disparities in Arkansas: A Multiple Year Study.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2015.

Resnick, Judith. Impermissible Punishments: How Prison Became a Problem for Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2025.

Smith, Ryan Anthony. “Gendered Confines: Women’s Prison Reform in 1920s and 1930s Arkansas.” MA thesis, Arkansas State University, 2017.

Thompson, Connor. “Out of the Shadows: The Case for Arkansas to Achieve Full Compliance with the Prison Rape Elimination Act.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review 43 (Spring 2021): 65–86.

Trimble, Mike. “Full House.” Arkansas Times, March 1989, pp. 54–58, 60–62, 64.

Zimmerman, Jane. “The Convict Lease System in Arkansas and the Fight for Abolition.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 8 (Autumn 1949): 171–189.

Steven Teske

CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.