calsfoundation@cals.org

Battle of Helena

| Location: | Phillips County |

| Campaign: | Grant’s Operations against Vicksburg |

| Date: | July 4, 1863 |

| Principal Commanders: | Major General Benjamin Prentiss (US); Lieutenant General Theophilus H. Holmes (CS) |

| Forces Engaged: | District of Eastern Arkansas (US); District of Arkansas (CS) |

| Estimated Casualties: | 239 (US); 1,614 (CS) |

| Result: | Union victory |

The Confederate attack on the Mississippi River town of Helena (Phillips County) was, for the size of the forces engaged (nearly 12,000), as desperate a fight as any in the Civil War, with repeated assaults on heavily fortified positions similar to the fighting that was to be seen in 1864 in General Ulysses Grant’s overland campaign in Virginia and General William T. Sherman’s Atlanta, Georgia, campaign. It was the Confederates’ last major offensive in Arkansas (besides cavalry raids and the repulse of the Camden Expedition) and the last Confederate attempt to seize a potential choke point on the Mississippi. But the Battle of Helena has been little noted and not long remembered because it was fought the day the Confederate garrison at Vicksburg, Mississippi, surrendered to Grant and the day after the Battle of Gettysburg.

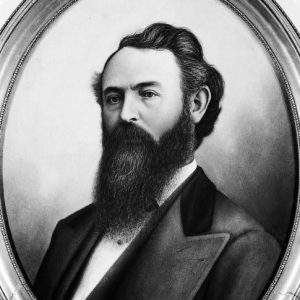

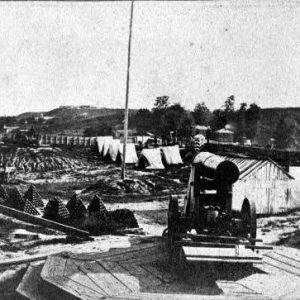

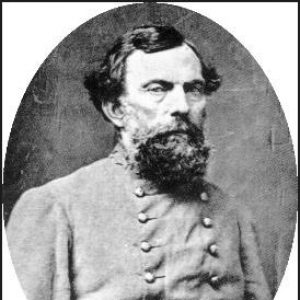

Federal forces under Major General Samuel Ryan Curtis occupied Helena in July 1862. Dubbed “hell in Arkansas” by a wag in the garrison, Helena became a major Union logistical base on the Mississippi River, strategically located not far above Vicksburg. Helena is on the high ground of Crowley’s Ridge, which creates an excellent defensive position, though it could be a death trap if the enemy took the high ground on the bluffs beyond the town. Helena’s strategic importance increased when Grant laid siege to Vicksburg. In mid-June 1863, Lieutenant General Theophilus Holmes, commander of the Confederate District of Arkansas, decided to attack Helena after prodding from Secretary of War James Seddon and Lieutenant General Kirby Smith. Holmes had been hesitant until Helena’s garrison was depleted for the siege of Vicksburg.

On June 18, Holmes met with Major General Sterling Price and Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke in Jacksonport (Jackson County) to plan the attack. Holmes issued an order: “The invaders have been driven from every point in Arkansas save one—Helena. We go to retake it.” Although tagged as vacillating and dilatory, once committed, Holmes swiftly set the campaign in motion and attacked Helena. Setting off from Jacksonport on June 22, Price’s infantry and Marmaduke’s cavalry made a ten-day march covering sixty-nine miles to Moro (Lee County) on rain-soaked roads. They crossed Grand Prairie, then improvised a ferry over Bayou De View after a bridge constructed by Price’s engineer, Lieutenant John Mhoon, was washed away. While Price and Marmaduke’s troops converged on Helena, a second column of infantry commanded by Brigadier General James Fagan advanced from Little Rock (Pulaski County). Fagan’s men had an easier march, being able to travel by rail and steamboat as far as Clarendon (Monroe County).

A Confederate council of war took place July 3 at the Allen Polk house five miles west of Helena. Helena’s fortifications were stronger than expected, but those present approved Holmes’s plan for a converging attack with his 7,646 troops effective to commence at “daylight” the next day, with Fagan attacking from the southwest, Price from the west, and Marmaduke from the north. Holmes’s plan of attack was made without adequate reconnaissance and a lack of intelligence as to the strongly fortified Union defensive positions.

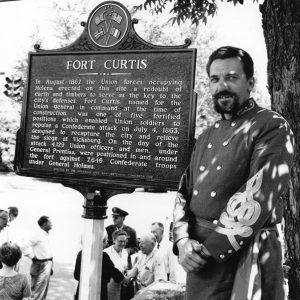

Union Major General Benjamin M. Prentiss had learned at Shiloh in Tennessee about the need for prepared positions. He established four fortified positions on the bluffs north and west of town, Batteries A and B to the north taking advantage of Rightor Hill, Battery C west of the city on Graveyard Hill, and Battery D near the home of General Thomas Hindman on Hindman Hill southwest of town commanding the Upper Little Rock Road. Also, a heavily fortified redoubt called Fort Curtis was built at the city’s western edge.

The attack was no surprise, because word of the Confederate advance had already reached Prentiss. The Union army, 4,129 strong, was under arms at 2:30 a.m. Prentiss had trees cut to block the approach roads, and, although Holmes’s infantry crawled through this obstacle, most Confederate artillery could not advance.

Firing broke out along the picket line at 3:00 a.m. Holmes’s order to attack at daylight proved imprecise. Price apparently left the council of war thinking that “daylight” meant “dawn,” while Fagan understood it as “first light.” Launching the attack on Hindman Hill (Battery D) at first light, a full hour before Price, Fagan’s men suffered heavily under enfilading fire from Graveyard Hill (Battery C) to Fagan’s left. Fagan’s men carried lines of rifle pits but could not reduce Battery D.

Price’s men wandered through broken country before attacking at dawn. Storming up Graveyard Hill, Price’s infantry took Battery C. The troops tried to turn the guns on the enemy but found them disabled. A charge on Fort Curtis resulted in heavy Confederate casualties and accomplished nothing. Attempts to help Fagan’s troops take Hindman Hill also failed.

To the north, Marmaduke’s cavalry failed to take Rightor Hill, stymied by troops under Colonel Powell Clayton in a flanking position on the Union right behind the levee. Colonel Joseph Shelby’s attack was repulsed. (Marmaduke’s anger about Brigadier General Marsh Walker’s failure to advance on the right resulted in a Little Rock duel on September 6, 1863, in which Marmaduke killed Walker.)

The defenders along the line were materially aided by supporting fire from the timber-clad USS Tyler. Acting Ensign George L. Smith reported firing 413 rounds, mostly eight-inch ten- and fifteen-second shells. At 10:30 a.m., Holmes ordered his army to withdraw. Large groups of Confederates trapped in ravines surrendered, including Colonel Samuel Bell, Lieutenant Colonel Jeptha C. Johnson, and more than 100 men of the Thirty-Seventh Arkansas, after trying to take Hindman Hill from the south. The Confederates retreated unmolested by Prentiss, who feared a renewal of their attack.

The Second Arkansas Infantry (African Descent) held the extreme left of the Union line. Although these troops were not directly attacked and suffered only five wounded, the role they played in the battle received wide notice in the Northern abolitionist press.

From the Confederate point of view, the Battle of Helena was a tragic waste. The bloody attack turned out to be a cruel and pointless irony, coming as it did on the day Vicksburg fell. Holmes’s army clearly brought with it to Helena a fighting spirit, but morale suffered badly after such a repulse. The fierce riverside battle was the unsuccessful culmination of the last major Confederate offensive in Arkansas. Soon after, only cavalry raids and guerrilla activity would trouble Union forces north of the Arkansas River, and the state capital, ten weeks later, slipped from Confederate control. For the Union, Helena represented the long-awaited crack in the Arkansas Confederates’ façade.

For additional information:

Bears, Edwin C. “The Battle of Helena, July 4, 1863.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20 (Autumn 1961): 256–297.

Christ, Mark K. Civil War Arkansas, 1863: The Battle for a State. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010.

Christ, Mark K., ed. Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

———. “‘We Were Badly Whipped’: A Confederate Account of the Battle of Helena, July 4, 1863.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 69 (Spring 2010): 44–53.

Hanna, Harvey. “The Battle of Helena.” Arkansas Times, June 1991, pp. 52–57.

Schieffler, George David. “Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2017. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2426/ (accessed October 8, 2024).

———. “Too Little, Too Late to Save Vicksburg: The Battle of Helena, Arkansas, July 4, 1863.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2005.

Sperry, A. F. History of the 33rd Iowa Infantry Volunteer Regiment, 1863–6. Edited by Gregory J. W. Urwin and Cathy Kunzinger Urwin. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Michael W. Taylor

Albemarle, North Carolina

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.