calsfoundation@cals.org

Bald Knob (White County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35º18’35″N 091º34’04″W |

| Elevation: | 231 feet |

| Area: | 4.95 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 2,522 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | September 16, 1881 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

707 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

617 |

958 |

1,273 |

1,445 |

2,022 |

1,705 |

2,094 |

2,756 |

2,653 |

3,210 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2,897 |

2,522 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Located on the southern edge of the Ozarks, White County’s Bald Knob was named for a large outcropping of layered stone that was a natural landmark, especially if approached from the White River and Little Red River floodplains east and south of town. The completion of the St. Louis, Iron Mountain, and Southern Railroad in 1872 triggered economic development in the region.

Liberty Valley, south of Bald Knob, is the site of prehistoric salt extraction. Some scholars hypothesize that this is the site of Palisima, a Native American village mentioned in documents from the Hernando de Soto expedition.

During the Civil War, workers extracted about two bushels of salt a day by boiling the water in large kettles. In the area’s only notable Civil War incident, Union troops broke most of the kettles on August 10, 1864. Some kettles still remain in private possession in the vicinity.

The area, sparsely settled before the war, was initially named Shady Grove after a church and schoolhouse in what is now the northwest part of town. With the railroad’s arrival in 1872, officials became interested in quarrying the bald knob for railroad bed ballast. Work in the quarry began in 1877, and, by 1880, fifty-six of the town’s 221 people worked there. More than half of the quarry workers were foreign born, most from Ireland. The importance of rock quarrying continued as the knob furnished ballast for Jay Gould’s Bald Knob Memphis Railroad, built in 1886–1888 to make an east-west connection for the St. Louis, Iron Mountain, and Southern. By 1900, the quarry had wound down, but it was reopened briefly in the 1920s to furnish rock for buildings at Southwestern College (now Rhodes College) in Memphis, Tennessee.

Benjamin Franklin Brown, one of Bald Knob’s founding fathers, posted a sign beside the railroad tracks about 1873 labeling the area Bald Knob. In February 1878, Lunsford Worthington applied for a post office, and 150 families soon received mail at the new station. In 1881, Merrival F. Dumas was elected the first mayor.

Harvesting of the vast hardwood forest of the White River and Little Red River bottoms began in the late 1870s with small sawmills. The number and size of the mills reached a high in the 1930s when the Fisher Body Company of Memphis required eighty railcars of hardwood logs daily, to be used in the body supports of General Motors automobiles.

The strawberry triggered another economic surge for Bald Knob. The sandy, upland soil was ideal for the fruit, which was introduced in neighboring Judsonia (White County) in the 1870s. The first strawberry association in Bald Knob was organized in 1910. In 1921, Brown, June “Jim” Collison, and Ernest R. Wynn organized The Strawberry Company. They built the longest strawberry shed in the world, a three-quarter-mile structure parallel to the tracks of the Missouri Pacific Railroad (now Union Pacific). In the peak year of 1951, Bald Knob growers sold $3.5 million worth of strawberries. Bald Knob became the “Strawberry Capital of the World,” which described the city until the 1960s, when berries ceased to be a major crop because of changing market and labor conditions.

The Great Depression brought public works programs to Bald Knob. The National Youth Administration built a gymnasium for the high school. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) improved rural roads. The WPA also built a new schoolhouse for School District No. 45 northwest of town. The No. 45 Schoolhouse is on the National Register of Historic Places because of its representation of Prairie-style architecture. Today, the Hopewell Community Church occupies it.

Bald Knob’s citizens pitched in to aid the World War II effort by buying war bonds, rounding up scrap metal, and rationing sugar, butter, gasoline, and tires. At least seventy-six community members entered military service. This included the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAC); Ruth Blanton served in Allied headquarters under General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s command at the end of hostilities in Europe.

Bald Knob’s agriculture changed again in 1953, when rice and soybeans became prominent. Bottomlands that once had been covered with hardwood were cleared and planted in these crops. A severe drought in 1980 and worldwide economic conditions led to a period of economic distress for farmers of Bald Knob and all Arkansas. Rice remains an important crop.

The Bald Knob School District, at first a two-teacher school, was formed in 1897 from the old Shady Grove District. Numbers of students and faculty increased over the years until all twelve grades were taught in 1927. Much of the physical plant was destroyed in a March 1952 tornado. Four years later, Bald Knob schools gained accreditation from the North Central Association. The campus also hosts a branch of Arkansas State University–Searcy Career Center.

Hunting and fishing opportunities bring people to the Henry Gray/Hurricane Lake Wildlife Management Area, which contains 17,000 acres supervised by the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission. The area was formerly owned by the Fisher Body Company. It became state property in 1941 and has been enlarged over the years. In 1993, the Bald Knob National Wildlife Refuge was established on 14,800 acres south of town.

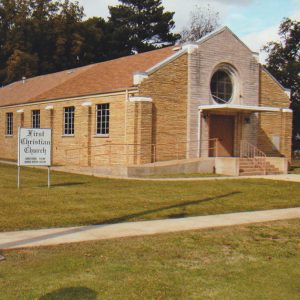

The 1915 train depot, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, was restored in 2004 to become the home of a model train shop. Other National Register properties include St. Richard’s Catholic Church, a classic example of the Park or Rustic style, and the First United Methodist Church, recognized as one of the finest examples of Tudor architecture in Arkansas.

For additional information:

Johnson, Lincoln, and Elizabeth Short. In and Around the Big Rock: A History of Bald Knob, Arkansas. Columbus, GA: Quill Publications, 1988.

White County Arkansas. https://www.whitecountyar.org/ (accessed April 13, 2022).

William E. Leach

White County Historical Society

Bald Knob Church

Bald Knob Church  Bald Knob Depot

Bald Knob Depot  Bald Knob Flood

Bald Knob Flood  Bald Knob State Bank

Bald Knob State Bank  Bald Knob Street Scene

Bald Knob Street Scene  Bald Knob Street Scene

Bald Knob Street Scene  Bald Knob Street Scene

Bald Knob Street Scene  Bald Knob Train Depot

Bald Knob Train Depot  Kelley’s Grill

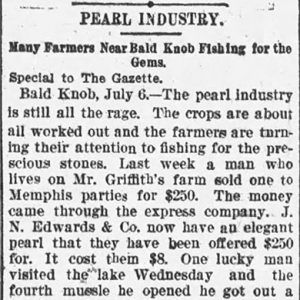

Kelley’s Grill  Pearling Article

Pearling Article  White County Map

White County Map

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.