calsfoundation@cals.org

1861 - 1874

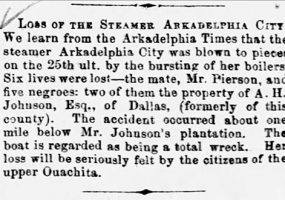

Civil War through Reconstruction

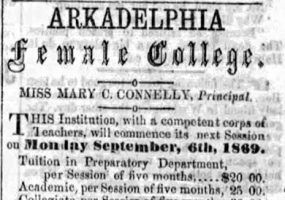

aka: Arkadelphia Female Seminary

aka: Arkadelphia Female College

aka: Arkadelphia Female Academy

aka: Battle of Post of Arkansas

aka: Action at DeValls Bluff