calsfoundation@cals.org

The Foundation of Knowledge

Probably in late elementary school or early junior high, I began reading a lot of classic science fiction, especially the novels of Isaac Asimov. I was particularly entranced with his Foundation series, which begins in the waning days of the Galactic Empire. The mathematician Hari Seldon develops a discipline called psychohistory, which can within a margin of error predict the future of large populations. Using his techniques, he foresees the inevitable collapse of the empire and a dark age spanning dozens of millennia. To temper the resulting age of chaos, Seldon assembles a group of people on the planet Terminus, at the edge of the galaxy, to assemble the Encyclopedia Galactica, thus preserving all of human knowledge for the time when a second empire might arise.

I was a bookish lad from the get-go, and as soon as I started the Foundation series, my daydream was to be one of those encyclopedists living on some distant planet on the rim of the Milky Way, with all of human knowledge at my fingertips and the stern commandment to save it for when it might be used again. And, funny enough, here I am, an encyclopedia editor for the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas (EOA). Arkansas may not be on the edge of the galaxy, but it’s certainly on the edge of the national consciousness. As to whether or not we are currently entering a dark age, I leave that to you.

Back then, I imagined knowledge as largely cumulative. Knowledge was the record of those dates and places people say so often make up the sum total of history as a discipline. Knowledge was the record of techniques needed to carry out important tasks, be it making a nuclear bomb or baking a loaf of sourdough. Knowledge was the discretely labeled places on the maps in the glove compartment.

At the same time, I was starting to learn that knowledge is not just cumulative but also interpretative. Like points on a graph, when we have two facts, we can draw a line, and when we have more, we can produce more interesting shapes. What shape should be produced is a matter of debate, of course—some shapes will be more natural manifestations of the points in question, but maybe other shapes might show us something surprising about how these points relate to each other.

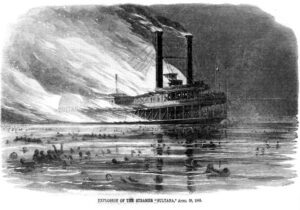

Let’s take the EOA’s entry on steamboat disasters, as an example. There is a nice chart at the end listing a whole host of fatal steamboat disasters that happened on Arkansas waters, giving the name of the steamboat, the date of the event, the type of disaster it was, and the river on which it happened. And we have links to all those separate steamboat disaster entries. Those are nice, discrete facts that you can plot as you will. But with those points on your graph, you can start to draw some interpretations from the data. A certain number of snags on a particular river might well give evidence to that being a particularly dangerous waterway. Likewise, the prevalence of boiler explosions on certain well-worn trade routes might suggest steamboat captains pushing the limits of their machines or not investing in repairs in order to keep costs low as they rush to get goods to market. The first might hint at something about local environmental history, while the latter tells us something about bare-knuckle capitalist ventures in the Lower Mississippi River Valley.

The facts are important, but they need to be interpreted to tell us anything meaningful. And I’ll go even further than that and say this:

Interpretation lies at the heart of creation.

That is, interpretation is the essence of the creative enterprise. Psychologists have developed, as a measure of individual creativity, the Remote Associates Test, on the basis that creativity depends upon one’s ability to make associations between varied ideas or concepts. The test asks the user to type in a word relating to three others presented. So, on the easy scale, something like cottage, Swiss, cake very obviously yields cheese. On the harder end are sets like fence, card, master, which should yield post.

Creativity depends upon interpreting things in context of each other. Or as Kirby Ferguson titled his web series on the subject, “Everything Is a Remix.” The work we find most exciting takes disparate genres and characters and blends them together in unique ways. Creative projects feel fresh when they take from a broad array of influences. It’s why the original Star Wars series remains so watchable, because it stole from westerns, Japanese samurai movies, and old Buck Rogers serials, and it’s why the newer ones have often fallen flat, for they steal primarily from older Star Wars movies.

That holds for scholarship, too. The potential interpretations of steamboat disasters I mentioned earlier comes to me courtesy of Walter Johnson’s 2013 book River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom. In addition to examining steamboat captains as frontier capitalists running their boats and crew ragged in order to turn a larger profit, Johnson also explored two significant implications of southern cotton monoculture: 1) cotton is not food, and so folks trying to escape slavery cannot easily steal from the fields to feed themselves while on the run, and 2) the lower height of the cotton plant makes hiding in a field more difficult for an adult, further challenging one’s ability to escape.

When someone insists upon including these points, these lines, in the broader picture, it can change how we perceive the whole. Suddenly, it wasn’t just a matter of master versus slave, but the very earth itself was cultivated and distorted in a way to make it yet one more enemy of the bondsman. That’s a different picture than we had before. That makes slavery so much more pervasive a system.

I rather still like that idea of the Foundation, existing like a monastery on the edge of the cosmos, waiting for when mankind is meek enough to be civilized again with the knowledge it holds. But knowledge held in isolation is not knowledge, as Virginia Woolf herself discovered when, as she notes in A Room of One’s Own, she attempted to glean from older books some hint of the creative lives of women in generations gone past: “Whatever the reason, all these books, I thought, surveying the pile on the desk, are worthless for my purposes.”

Knowledge is never an is. Knowledge is always a becoming. And knowledge must circulate and be seen by different eyes and be connected to an array of other concepts, some of them so remote so as to be absurd, in order to become what it can be. It cannot abide in isolation at galaxy’s edge, waiting for the perfect moment. That moment is now.

By Guy Lancaster, editor of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas