calsfoundation@cals.org

Get to Work!: Slouching toward the Absolute

“I might eventually write something, but right now I’m just enjoying the research too much.”

I hear these words often, and they set me on edge each time. Usually, someone has just told me about some research they have undertaken, something that sounds really promising, something that could easily be an article or even a book. Not only do I like to encourage people’s personal and professional development, but I also know that Arkansas history as a field needs such contributions. And I’m also acquainted with more than a few editors in need of new submissions in order to keep afloat the journals they publish. Thus do I say, “You should write this up and submit it somewhere.”

Then I hear those words I’ve posted above. Sometimes, I also hear, “I just like digging in the archives more than I like writing anything.” Or: “I want to get everything down perfectly before I send anything off. I would hate to miss something.”

I’m forty-seven years old. I’ve been working at my current job for nearly eighteen years. And I’ve had the same conversation with some of the same people about the same research projects over a course of many years.

If you are one of those people, you need to understand this very simple truth:

Knowledge does not exist until it is shared with others.

Also:

Whatever you publish will be incomplete no matter how much time and energy you spend on the research.

Let’s tackle the first assertion. You can know some fundamental truth about the universe, but until you write it down, until you share that truth with someone else, it may as well not exist. You can figure out in your own head the nature of dark matter and the mysteries of the Big Bang, but if you get hit by a bus the next moment, that fundamental insight into creation vanishes with you.

Our modern usage, especially in various popular science books, treats cognition very much as an individualistic act. Cognition is the act of a brain in isolation. Except, in human culture, brains are never in isolation, and the word cognition itself is derived from the Latin com (“together” or “with”) and gnoscere (“to know”). When we think, we use words that we have inherited from the people around us, as well as concepts in common circulation.

Knowledge exists when it is shared. And for the field of history, that form of sharing is predominantly written, in order that sources might be double-checked by those who come after. We owe it to others to share what we uncover. A contribution is the tribute that is owed to the wider community of scholars, the tribute we owe each other, together.

Now the second point. Anything you might publish will be incomplete because this is the nature of things. For starters, you simply have no idea what theoretical approaches might be developed in the future. More than that, however, even if you scour every available source and resource (and this is unlikely), sometimes you simply won’t be able to complete the story unless you publish your incomplete history. The historian Aaron Lecklider recently wrote a piece for Slate on his attempt to track down a queer man, known only by his initials, who had written a heart-felt letter published in the January 1929 issue of New Masses, a popular leftist magazine, about his same-sex attractions and the loneliness he felt. Lecklider had no luck finding information about this man and went ahead with the publication of his 2021 book, Love’s Next Meeting: The Forgotten History of Homosexuality and the Left in American Culture, but two years after that, precisely because he had published this book, a historian working in the archives in Belfast contacted him with a fortuitous discovery of letters that seemed to be by the same person. The story is now more complete precisely because Lecklider dared to publish an incomplete story.

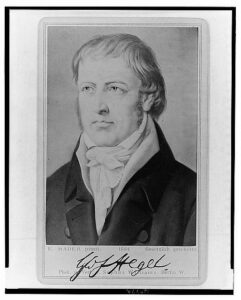

So I’m currently reading G. W. F. Hegel’s 1807 book, The Phenomenology of Spirit. The reasons for this are rather convoluted, and my attempt to engage with this book has necessitated the purchase of multiple other books. Sometimes, a clear idea seems to shine forth, and at other times I find myself at sea in a mélange of obscurantist phraseology that, I am told, wasn’t really any clearer in the original German. But as I understand it, according to Hegel, we are both, as individuals and as societies (and even humanity as a whole), slowly struggling toward Absolute Spirit, but we can only arrive at that point where we experience Truth and Wholeness by engaging with parts.

So I’m currently reading G. W. F. Hegel’s 1807 book, The Phenomenology of Spirit. The reasons for this are rather convoluted, and my attempt to engage with this book has necessitated the purchase of multiple other books. Sometimes, a clear idea seems to shine forth, and at other times I find myself at sea in a mélange of obscurantist phraseology that, I am told, wasn’t really any clearer in the original German. But as I understand it, according to Hegel, we are both, as individuals and as societies (and even humanity as a whole), slowly struggling toward Absolute Spirit, but we can only arrive at that point where we experience Truth and Wholeness by engaging with parts.

Bertrand Russell summarized the Hegelian view thusly in The Problems of Philosophy: “Every apparently separate piece of reality has, as it were, hooks which grapple it to the next piece; the next piece, in turn, has fresh hooks, and so on, until the whole universe is reconstructed.” Kenneth R. Westphal, in his contribution to The Bloomsbury Companion to Hegel, described Hegel’s system as one in which “wholes and parts are mutually interdependent for their existence and characteristics.”

The point here is this: It is necessary for us to engage with fragments if we want any hope of building a path toward the whole. Anything we publish will be a fragment no matter how determined we are otherwise, but fragments are the worthiest tribute we can provide to the larger body of scholars, for our pieces may well fit the puzzles with which they have been struggling, and what they produce may answer some of our lingering questions. Or as Westphal writes in his 2003 book, Hegel’s Epistemology:

Hegel and his pragmatist successors are fallibilists; they recognize that human knowledge is corrigible, though they recognize that this is not a curse but instead a blessing. It is a blessing because whatever we may take as first premises, either in empirical knowledge or in guiding action, is justified only to the extent that those premises or principles are demonstrably superior to their alternatives, whether historical or contemporary, that they are adequate to their intended domains, and that they continue to perform their roles adequately in the face of renewed occasions of their use, often in changed circumstances.

In my own work, I have to recognize that, even if we manage to obtain entries on every conceivable Arkansas-related subject, the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas will never be complete. But its existence as a historical resource upon which future work can be built is demonstrably superior to its non-existence, even where it may later be demonstrated that we have this date or name incorrect. But by offering what remains incomplete, we provide guideposts to future historians to map out new lines of inquiry. We slouch ever diligently toward the Absolute. (And, since it is an online resource, we can continuously add and correct items as new information comes along.)

With that in mind, let me say this in closing: Turn in your damn entries already, and turn that idea you’ve been mulling forever into the article or book it deserves to be. The Absolute awaits. Get to work.

By Guy Lancaster, editor of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas