calsfoundation@cals.org

Whitewater Scandal

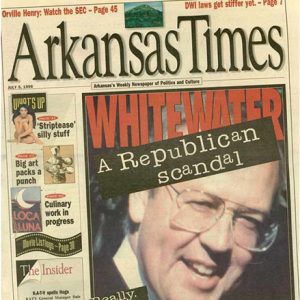

“Whitewater” was the popular nickname for a series of investigations of President William Jefferson Clinton that lasted nearly seven years and concluded with his impeachment by the U.S. House of Representatives and acquittal by the Senate, making him the second U.S. president to be impeached. The investigations began in 1994 as an inquiry by an independent U.S. counsel into the propriety of real-estate transactions involving Clinton and his wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, in 1978, when he was attorney general of Arkansas and shortly before he became governor. It morphed through many phases until the independent counsel looked into allegations of illicit sexual encounters when Clinton was governor and president.

The term “Whitewater” originated from the Whitewater Development Corporation, a company formed in 1978 by the Clintons and James B. and Susan McDougal to develop a 230-acre tract of remote mountain land at the confluence of the White River and Crooked Creek in Marion County. The two couples borrowed $203,000 from a bank to buy the land and make improvements. They hoped to sell lots for vacation homes and make a profit, but interest rates skyrocketed, the real-estate market plunged, and the couples lost most of their investment. McDougal, a political operative and friend of Clinton, acquired a bank in the tiny town of Kingston (Madison County) in 1980 and then, in 1982, a small savings and loan company in Woodruff County, which he renamed Madison Guaranty Savings and Loan Corporation and moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County). That enterprise also collapsed in the sweeping national savings and loan debacle of the 1980s. McDougal was tried and acquitted in federal District Court in 1990 on charges of bank fraud in connection with the savings and loan.

Whitewater resurfaced in 1992 when Clinton ran for president. The New York Times on March 8 published a lengthy account of the Whitewater investment as told by an embittered McDougal, who complained that he had borne an unfair share of the investment and the loss. Critics soon raised questions about Hillary Clinton’s representation of McDougal’s savings and loan company while she was an attorney at the Rose Law Firm in Little Rock, whether state regulators under Bill Clinton extended favors to the savings and loan in exchange for campaign funds, whether the Clintons properly paid taxes on the Whitewater business, and whether McDougal might have illegally channeled money from the savings and loan to the Whitewater project.

The Whitewater controversy quickened on July 20, 1993, six months into Clinton’s presidency, when Vincent W. Foster Jr., a close friend of the Clintons from Little Rock and a deputy White House counsel, was found dead of a gunshot wound to the head in Fort Marcy Park, a Civil War park maintained by the National Park Service just outside the District of Columbia. His death was ruled a suicide. Foster had handled Whitewater issues for the Clintons since the campaign and had become the focus of criticism in the media, mainly the Wall Street Journal. In his White House office, he left a bitter note about not having been meant for the spotlight in Washington DC, where “ruining people is considered sport.” Conservative groups promoted dark theories about how the Clintons had had Foster murdered because he might have to reveal Whitewater secrets.

On the same day that Foster killed himself, Paula Casey, the new U.S. attorney at Little Rock appointed by Clinton, obtained a federal search warrant for the Little Rock offices of David Hale, a municipal judge who ran a small-business lending company called Capital Management Services, which was subsidized by the federal Small Business Administration. The next day, FBI agents raided the offices, and on September 23, a federal grand jury indicted Hale. He had advanced $2.04 million to thirteen dummy corporations that he controlled. Hale’s business also had extensive transactions in the 1980s with the McDougals, Jim Guy Tucker (who by 1993 was governor of Arkansas), and several prominent Republican officials. Those transactions later formed the basis of criminal charges against James and Susan McDougal and Governor Tucker. After his indictment, Hale alleged that Clinton had a secret interest in one of his illegal loans and had pressured him to make it, although no records ever showed that Clinton had any transaction with Hale.

In January 1994, Clinton capitulated to the Republican clamor over Whitewater and told Attorney General Janet Reno to appoint a special counsel to investigate. Reno appointed Robert B. Fiske Jr., a Republican and a former U.S. attorney in New York. He was given broad authority to investigate Whitewater and any related activity. When David Hale complained that the U.S. attorney in Arkansas would not plea bargain with him in exchange for information about high officials, including Clinton, his case was transferred from the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Arkansas to the independent counsel. Over the next four years, Attorney General Reno or the supervising panel from the District of Columbia Court of Appeals referred other disputes to the Whitewater prosecutor, most significantly Clinton’s firing of seven members of the White House travel office; the collection of confidential FBI files on a number of Republicans by a minor White House operative in 1993 and 1994; the embezzlement of large sums of money from the Rose Law Firm by Webster Hubbell, a partner in the firm who became a deputy attorney general under Clinton; and, finally, allegations about cash gifts given to Hubbell when he came under scrutiny by Whitewater investigators.

In the summer of 1994, after Fiske concluded that Foster had committed suicide, conservative groups and Republican senators complained that his investigation was not diligent enough. A three-judge U.S. Court of Appeals panel replaced Fiske with Kenneth W. Starr, a former federal appeals court judge and already a harsh critic of Clinton. The switch raised ethical questions because the chairman of the panel, Judge David B. Sentelle, was a protégé of Republican senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina, and three weeks before dismissing Fiske, he had had lunch with Helms and Senator Lauch Faircloth, also of North Carolina, who had accused Fiske of not being tough enough on Clinton, specifically in his conclusion that Foster had committed suicide. Starr reopened the investigation of Foster’s death and issued new subpoenas for documents, including Hillary Clinton’s billing records when she was with the Rose Law Firm.

In the meantime, the Republican-controlled Senate appointed the Special Whitewater Committee to look into all the Whitewater-related matters, and the Banking committees of both the Senate and the House of Representatives undertook extensive hearings on Whitewater and Madison Guaranty Savings and Loan Corp. Numerous officials of the Clinton administration and associates of the Clintons from Arkansas were subpoenaed to testify. The Senate Whitewater hearings and the House Banking Committee hearings on Whitewater lasted more than a year but found no illegalities. Starr, the Whitewater special prosecutor, eventually concluded that Foster had committed suicide and that no laws were broken in the travel office firings or the FBI files case.

But Starr extended the investigation far and wide in Arkansas, delving into the business practices at the Madison Guaranty thrift, Hale’s small-business lending operations, Jim Guy Tucker’s cable television business in the 1980s, and Clinton’s campaigns for governor. Starr and Fiske obtained indictments against seventeen persons in Arkansas, fifteen of whom either pleaded guilty to offenses or were convicted. Most did not go to trial. Only one of the convictions was related by evidence to either of the Clintons: the president of a small bank at Perryville (Perry County) that had loaned money to Clinton’s campaign for governor in 1990 pleaded guilty to misdemeanors for failing to report two campaign bank loans to the U.S. Comptroller of the Currency, as a federal narcotics law required.

Aside from those who were indicted, many other Arkansans were swept up in the investigation—family members (including children) of those who were accused, people who had worked in Clinton’s state capitol office or his 1990 campaign for governor, employees of McDougal’s businesses, and associates in Washington after Clinton became president. Many hired lawyers to advise and represent them in the grand jury proceedings in Little Rock and Washington.

Although none of the investigations ever concluded that the Clintons did anything wrong in these matters, the original issue stayed alive until the independent counsel closed shop in 2001, mainly owing to David Hale’s contention that Clinton—while he was governor in the mid-1980s—had asked him to approve a $300,000 loan to Susan McDougal that proved to be fraudulent because its proceeds were misused by her husband. Clinton testified that he never heard about the loan. While she stubbornly refused to testify before the grand jury and went to prison for it, Susan McDougal publicly maintained that she never apprised Clinton of the loan because it had nothing to do with him.

James McDougal was convicted on eighteen counts of fraud and conspiracy in his dealings with Hale’s company in May 1996 and was sentenced to five years in prison, with two of them suspended. He had insisted upon his innocence, but after his conviction and facing a possible eighty-four-year prison sentence, he agreed to cooperate with Starr in exchange for a shortened sentence, claiming that he had been present when Clinton had brought up the loan in a conversation with Hale, although his and Hale’s accounts differed. He died in a federal prison in Fort Worth, Texas, on March 8, 1998.

Gov. Tucker was convicted of mail fraud and conspiracy in his dealings with Madison Guaranty and Hale, and he also pleaded guilty to filing a sham bankruptcy for a cable television company he owned in Texas. He served no time for either and tried unsuccessfully for years to reverse both convictions, losing finally with the U.S. Supreme Court. His conviction on the bankruptcy charge proved especially perverse for Tucker because the Justice Department and the Internal Revenue Service eventually conceded that the tax law that he was accused of violating had been repealed before the transaction and that rather than owing the government $3.5 million in taxes, his liability was no more than $125,000 and perhaps nothing. Tucker argued before appellate courts that his plea and his conviction should be voided because the prosecutor had pursued him under a non-existent law. The Eighth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals said in 2005 that he had to abide by his guilty plea, and the U.S. Supreme Court refused to take up his appeal.

At the same trial with her husband and Gov. Tucker, Susan McDougal was convicted of fraud in connection with the loan from Hale and was sentenced to two years in prison. She became a celebrity and, to many, a heroine for her refusal to testify before the Whitewater grand jury at Little Rock because she said Starr wanted her to make up stories about the Clintons. She served eighteen months in prison for civil contempt for her refusal. After finishing that sentence in 1998, she served two months of her two-year fraud sentence before U.S. District Judge George E. Howard ordered her released for health reasons. Starr then prosecuted her for criminal contempt and obstruction of justice for her refusing to answer questions before the grand jury. In April 1999, a federal jury acquitted her.

Although the Clintons survived all the original Whitewater investigations and the endless maneuverings in and out of courts from Little Rock to the U.S. Supreme Court with their integrity and popularity intact, the ceaseless controversy and distraction severely weakened Clinton’s presidency. Back in Arkansas, it profoundly changed the course of history. Although he was a political foe of Clinton, Tucker was caught up in the investigation for his private business conducted a decade earlier and was forced to resign as governor in 1996 after his conviction, allowing Lieutenant Governor Mike Huckabee, a Republican, to take over.

While none of the investigations of Whitewater and the business, political, and governmental practices of the Clintons and their aides uncovered proof of any wrongdoing by the president or his wife, Starr kept up the pursuit. Paula Corbin Jones, a former employee of the Arkansas Industrial Development Commission (now the Arkansas Economic Development Commission), filed a lawsuit in 1994 contending that Clinton had made sexual advances toward her in a Little Rock hotel room in 1991. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that trying the lawsuit would not distract Clinton from his duties as president. While that case was unfolding, Starr sent FBI agents searching for evidence of other infidelities by Clinton.

In October 1997, Linda Tripp, who had been taping conversations with her friend—White House intern Monica Lewinsky—about Lewinsky’s romantic liaisons with the president, tipped off the Rutherford Institute, a conservative group, about the affair, and the information was passed along to Paula Jones’s attorneys. Tripp had worked in the White House under President George H. W. Bush and briefly under Clinton but by then was an employee at the Defense Department public affairs office. Lewinsky was subpoenaed to testify in the Jones trial about her relationship with the president. On January 12, 1998, Tripp brought her tapes of Lewinsky’s conversations to Starr. He arranged for FBI agents to secretly record a conversation between Tripp and Lewinsky the next day, and on January 15, he requested and received permission from the Department of Justice and the judicial panel to expand the Whitewater investigation to the Lewinsky affair. In a deposition given under oath in the Paula Jones case, Clinton, alluding to a narrow definition of “sexual relations” that was prescribed by Jones’s lawyers, testified that he had not had sexual relations with Lewinsky. Summoned to Starr’s grand jury in Washington, Clinton acknowledged having intimate relations with Lewinsky but would not describe them and insisted that his testimony in the Jones deposition was technically accurate.

Starr delivered a report to Congress on September 9, 1998, citing eleven possible impeachable offenses arising from efforts by Clinton personally or through his associates to cover up his indiscretions with Lewinsky or sidetrack the investigation. They involved perjury, obstruction of justice, and abuse of power. On December 19, the House of Representatives, voting largely along party lines, impeached Clinton on two articles—perjury before the grand jury and obstruction of justice—by votes of 228 to 206 and 221 to 212. Republican House members, including Representative Asa Hutchinson of Arkansas, prosecuted the impeachment articles before the Senate early in 1999. On February 12, after hearing a dramatic closing argument for Clinton by former Arkansas senator Dale Bumpers, the Senate rejected the perjury article 45–55 and the obstruction of justice article 50–50; both needed a two-thirds majority, or sixty-seven votes. Clinton subsequently admitted giving false testimony in the proceedings and surrendered his license to practice law in Arkansas.

The active investigation ended in 2001, but the independent counsel office did not close until May 2004. The Whitewater investigation cost more than $70 million.

Whitewater widened the partisan divide and hardened American political discourse. In Arkansas, it destroyed the career of a promising young politician, Jim Guy Tucker; catapulted a young Republican, Mike Huckabee, into national prominence; and dramatically altered the lives of scores of men and women who were friends and associates of the Clintons, mere acquaintances of the couple, and a few strangers who were swept up in the investigations.

For additional information:

Clinton, Bill. My Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

Conason, Joe, and Gene Lyons. The Hunting of the President: The Ten-Year Campaign to Destroy Bill and Hillary Clinton. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

Dumas, Ernest. “Family Skeletons.” Arkansas Times, July 5, 1996, pp. 9–13.

———. “Now It Can Be Told.” Arkansas Times, December 8, 2000, pp. 10–11, 13–14, 16–17.

———. “The Politics of Whitewater.” Miami Herald, June 23, 1996, p. 29. Online at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CREC-1996-07-29/html/CREC-1996-07-29-pt1-PgS9082-2.htm (accessed July 12, 2024).

Haddigan, Michael. “On the Trail of Trapper Dozhier.” Arkansas Times, May 22, 1998, pp. 14–17.

Kalb, Marvin. One Scandalous Story: Clinton, Lewinsky & 13 Days that Tarnished American Journalism. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001.

Mabury, David. “In Search of Whitewater.” Arkansas Times, May 26, 1994, pp. 16–18.

McDougal, Jim. Arkansas Mischief: The Birth of a National Scandal. New York: Henry Holt & Co., Inc., 1998.

McDougal, Susan. The Woman Who Wouldn’t Talk. New York: Carroll & Graff, Publishers, 2002.

Stewart, James B. Blood Sport: The President and His Adversaries. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.