calsfoundation@cals.org

West Memphis Three

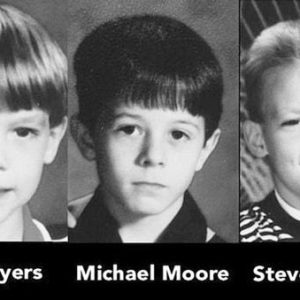

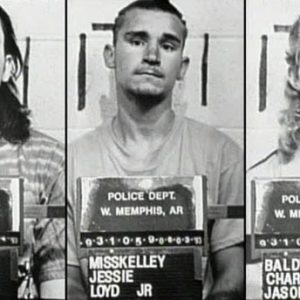

The West Memphis Three are Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley Jr., who—as teenagers—were convicted in 1994 of triple murder in West Memphis (Crittenden County). Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley were accused of killing three eight-year-old boys: Chris Byers, Stevie Branch, and Michael Moore. Their trial, which included assertions that the killings were part of a cultic ritual, and subsequent conviction set off a firestorm around the nation and world, inspired books and movies, and led to a movement to re-try or free the three men, believed by many to have been wrongly convicted.

On May 6, 1993, Byers, Branch, and Moore were found in a water-filled ditch in the woods of the Robin Hood Hills subdivision less than twenty-four hours after their parents had reported them missing. The boys were naked, beaten, and hog-tied. Byers had been castrated. Despite the violence of the crime, there was little evidence at the scene of the crime. Police wondered at the peculiar lack of blood or fibers, and also noted that the area looked as though it had been swept clean. The police were faced with a case that immediately gained national attention but that yielded little information with which to find the person or people responsible.

The state of the boys’ bodies quickly inspired rumors that a satanic cult was responsible. The crime scene’s location in the woods, the nudity, the positioning of the boys’ bodies, and especially the castration caused concern about Satanism amongst the locals, and amongst the police as well. Within days of the murders, Gary Gitchell, the chief inspector, informed the public that the police were considering a number of possible explanations for the murders, one of which was cult activity. Throughout the investigation, the cult theory overshadowed more traditional theories, such as the speculation that the murders were committed by someone who knew the boys.

Jerry Driver was a juvenile probation officer for Crittenden County who believed that there was a satanic cult in the area. Much of that belief was a result of his dealings with Damien Echols, a teenager placed under his supervision until age eighteen after having been arrested for burglary and sexual misconduct. The more that Driver interacted with Echols, the more convinced he became that Echols was involved in a satanic cult. Echols denied any connection with Satanism but did admit to believing in and practicing magic. Driver shared his suspicions with the West Memphis police.

Jason Baldwin was friends with Echols, both of them being social outcasts. Baldwin did well in school and did not join in Echols’s experimentation with magic. Despite their many differences, they spent a great deal of time together. The third and final suspect, Jessie Misskelley Jr., had little connection to either Echols or Baldwin. However, he babysat for Vicki Hutcheson, a woman who volunteered to help the police investigate. Hutcheson began to ask Misskelley questions about the case, and he agreed to introduce her to Echols, well-known as a suspect by that point.

Hutcheson told police that she persuaded Echols to take her with him to a witches’ gathering and that Misskelley went with them. As a result, Misskelley was taken to the police station for several hours of questioning, of which just over thirty minutes were recorded. At the end of the questioning, Misskelley confessed, implicating himself, Echols, and Baldwin. Misskelley’s confession, however, was inconsistent with details of the crime of which the police were already aware. While confessing, Misskelley at times contradicted his own story as well. In spite of the potential problems with Misskelley’s confession, the police arrested him, Echols, and Baldwin on June 3, 1993.

Almost immediately after confessing, Misskelley recanted. He stated that he had been confused by the behavior of the police and had attempted to cooperate without realizing the implications of his statements. However, the three boys remained in custody, and both the prosecutor and the defense teams began preparing for trial. During the process of gathering evidence, blood was found on a knife previously owned by John Mark Byers, Chris Byers’s stepfather. Byers had given the knife away shortly after the murders. The blood was determined to be consistent with Chris Byers’s blood as well as with Mark Byers’s blood. However, the police did not pursue this potential lead. The police also failed to pursue a potential lead called in by a local Bojangles restaurant. One of the employees witnessed a disoriented man covered in mud and blood enter the restaurant the night the boys went missing. The man used the restroom, leaving smears of the blood he was covered in on the walls. Though the police took samples of the blood, they never pursued this lead and later lost the evidence.

Because Misskelley had confessed to the police, his trial was severed from Baldwin and Echols’s trial. Prosecutor John Fogleman wanted Misskelley to be able to testify against Baldwin and Echols, but Misskelley refused to repeat the statements that he had previously given and recanted. Misskelley’s trial began on January 26, 1994. Baldwin and Echols were tried a month later, beginning on February 28. Both trials drew much media attention, and there were significant legal complications as Judge David Burnett, Prosecutor Fogleman, and each defendant’s defense team determined what evidence could be submitted before the jury. Evidence the jury was allowed to hear included testimony from a cult expert who indicated that the defendants’ music collections and clothing were key indicators of satanic cult activity. The other evidence presented to the juries was similarly circumstantial. Defense attorneys failed to present more substantial evidence regarding the nature of the police investigation or the retraction of key testimony due to both their trial strategies and the judge’s refusal to allow the evidence to be heard. At both trials, the juries determined that the defendants were guilty of the crimes they were accused of. Misskelley and Baldwin were both sentenced to life in prison, with an additional forty years tacked on for Misskelley. Echols was sentenced to death.

After the initial trials, the West Memphis Three’s defense teams attempted numerous appeals claiming trial misconduct, presented new evidence, and challenged rulings against the inclusion of evidence that defense lawyers felt would be beneficial to their case. Outside of the courts, the case continued to fall apart. Vicki Hutcheson claimed that she had committed perjury when she testified against the three and stated that the police had told her what to say. The foreman of the jury was also accused of misconduct after it came to light that during the trial he had discussed the case at length with his own attorney. The accusation of juror misconduct—combined with new evidence showing that DNA found at the crime scene matched Terry Hobbs, Stevie Branch’s stepfather—was eventually used to secure a new hearing.

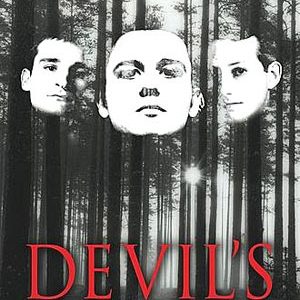

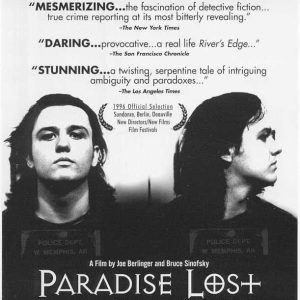

The West Memphis Three case has inspired numerous individuals to intervene on their behalf. Bruce Sinofsky and Joe Berlinger created a documentary about the West Memphis Three, Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills, and released it in 1996, hoping to encourage the public to remain interested in the fate of the three convicted men. (Sequels to the documentary were released in 2000 and 2012.) Burk Sauls, Kathy Bakken, and Grove Pashley, three friends from Los Angeles, California, traveled to Arkansas to visit Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley in October 1996. Upon deciding that they believed the West Memphis Three to be innocent, the three friends created a website, “Free the West Memphis Three,” to inform the public about the case as well as to ask for donations to help fund the defense team. Mara Leveritt, an Arkansas reporter, wrote a book titled, Devil’s Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three (2002) in response to a challenge made by state officials that a true, honest examination of the case would prove the guilt of the three defendants. After extensive research, Leveritt concluded that the entire situation was a tragedy and a gross miscarriage of justice. Numerous celebrities agreed with Leveritt. Eddie Vedder of the rock group Pearl Jam visited Echols on death row and used his music and fame to spread the message that Echols and the others were innocent. Actor Johnny Depp and singer Natalie Maines of the group the Dixie Chicks also leant their support.

On November 4, 2010, after numerous failed appeals, the Arkansas Supreme Court ordered that a hearing take place in order to analyze new evidence that had the potential to exonerate the West Memphis Three. Preparations began immediately. Echols hired a new defense team that included Stephen Braga and Patrick Benca. However, as the new lawyers worked to present their case at the hearing, they were dismayed to find that the new evidence did not conclusively point to a different perpetrator. As was typical for this case, the evidence was only circumstantial. Braga and Benca, convinced that the West Memphis Three were innocent and deserved their freedom, decided to take a different approach. Benca had a working relationship with Arkansas attorney general Dustin McDaniel. The two met to discuss the case. During that meeting, Benca asked McDaniel if his team would consider skipping the hearing in order to move straight to new trials. The judge, Benca argued, would certainly grant new trials after considering the jury misconduct discovered years before. McDaniel agreed to discuss the idea with his team.

As negotiations between the lawyers continued, Benca and Braga suggested that both sides agree to an Alford plea, with time served, in order to avoid the risk to both sides that a new trial would bring. An Alford plea required the three defendants to plead guilty to a series of lesser charges while at the same time stating for the record that they were innocent and only pleading guilty because it was in their best interest. Both legal teams agreed that the plea would be acceptable provided that all three defendants were willing to cooperate.

Despite this hopeful new development, Benca and Braga were still concerned. Jason Baldwin, by this time in his late thirties, had the most to lose by accepting this plea. Untainted by false confession as Misskelley was and without the threat of death row that Echols faced, Baldwin was unsure that pleading guilty was the answer. However, after considering that Echols’s execution date was quickly approaching, Baldwin agreed to the legal maneuver in order to preserve Echols’s life. On August 19, 2011, Judge Laser approved the Alford plea. Each of the defendants pleaded guilty while maintaining their innocence and were released on time served. After eighteen years, one of Arkansas’s most controversial murder cases came to a strange, semi-permanent close. Benca suggested that the defense team would continue pursuing the West Memphis Three case by petitioning Governor Mike Beebe for pardons. However, Beebe suggested that those petitions would be unsuccessful.

Despite the release of the West Memphis Three, the case remains unresolved, and the legal conduct of both the prosecution and the defense remain relatively unexamined. Prosecutors will not continue to investigate the murders of Stevie Branch, Chris Byers, and Michael Moore. Echols, Misskelley, and Baldwin will not receive compensation for time spent in prison, and they may never be cleared of the crimes to which they pleaded guilty. However, the case continues to inspire media attention. In 2012, the documentary West of Memphis, produced by Peter Jackson and Damien Echols and directed by Amy Berg, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival; a movie adaptation of Devil’s Knot began filming; and Echols published his memoir Life after Death.

In July 2021, it was reported, pursuant to a request by Echols’s attorneys for access to evidence from the crime scene for purposes of conducting new DNA testing, that the physical evidence relating to the three murder victims had been lost, misplaced, or destroyed by fire. However, later investigation found most of the evidence still intact. Echols filed suit for access to the remaining evidence for an enhanced DNA testing that was unavailable at the time the case was originally tried, but on June 23, 2022, Circuit Judge Tonya Alexander ruled against him. On January 9, 2023, attorneys for Echols asked the Arkansas Supreme Court to reverse Alexander’s ruling. Later that year, the Innocence Project, the Center on Wrongful Convictions, and a group of people who had been wrongfully convicted of crimes publicly urged the state Supreme Court to allow this new DNA testing. On April 18, 2024, the Arkansas Supreme Court ruled that a person entering an Alford plea did not lose the right to file a petition under Act 1780 of 2001, an act allowing someone “convicted of a crime” to seek to vacate the judgement provided that “scientific evidence, not available at the time of the trial, establishes the petitioner’s actual innocence,” and thus permitted Echols to carry out further testing on DNA evidence.

For additional information:

Dunning, Eric Moore. “From Courtroom to Chatroom: The Online Social Movement to Free the ‘West Memphis Three.’” PhD diss., University of Alabama, 2012. Online at https://ir.ua.edu/handle/123456789/1458 (accessed June 23, 2022).

Echols, Damien. Life after Death. New York: Blue Rider Press, 2012.

Echols, Damien, and Lorri Davis. Yours for Eternity: A Love Story on Death Row. New York: Blue Rider Press, 2014.

Exonerate the West Memphis Three Support Fund. http://www.wm3.org/ (accessed January 19, 2022).

Farrar, Lara. “Sources: Evidence in 3 Boys’ Case Gone.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, July 11, 2021, pp. 1B, 5B. https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/jul/11/sources-evidence-in-3-boys-case-gone/ (accessed January 19, 2022).

Koon, David. “Jason’s Choice: Friendship, Freedom, and a Principled Stand.” Arkansas Times, August 24, 2011. http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/jasons-choice/Content?oid=1888400 (accessed January 19, 2022).

Lancaster, Bob. “The Devil on Trial: Some Concluding Thoughts on the State’s Most Notorious Murder Case.” Arkansas Times, April 7, 1994. http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/the-devil-on-trial/Content?oid=1886123 (accessed January 19, 2022).

Leveritt, Mara. “Are ‘Voices for Justice’ Heard?: A Star-Studded Rally on Behalf of the West Memphis Three Prompts the Delicate Question.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review 33 (Winter 2011): 137–160.

———. Devil’s Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three. New York: Atria Books, 2002.

———. “Witch on Death Row.” Arkansas Times, June 23, 1994, pp. 9–12.

Leveritt, Mara, with Jason Baldwin. Dark Spell: Surviving the Sentence. Little Rock: Bird Call Press, 2014.

Morgan, James. “Murder Most Foul.” Arkansas Times, June 7, 1996, pp. 10–15.

Stidham, Dan, and Tom McCarthy. A Harvest of Innocence: The Untold Story of the West Memphis Three Murder Case. N.p.: 2023.

“Who Are the West Memphis Three?” Arkansas Times, August 19, 2011. http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/who-are-the-west-memphis-three/Content?oid=1886216 (accessed January 19, 2022).

Laura Choate

Conway, Arkansas

I’m wondering if anyone watching the video series Paradise Lost documentary caught Mike Myers stating that his wife was murdered in his discussion with the polygraph tester? It’s at 1:11:50. I had to watch it several times to make sure that it’s what I heard, but I thought it was important.

I have read books about this case for years, and still I believe this is a prime example of incompetence and laziness in police work, and that bothers me incredibly. The West Memphis Police Department has taken an oath to protect the citizens of their community, yet clearly they haven’t. Three boys have been murdered, three other men have had 18 years of their lives taken away for nothing, yet all the PD is concerned about is covering their own bases so they can never admit they made a mistake. It’s clearly disgusting, and everyone with an ounce of intelligence can see they have made a huge mistake, one they will never admit to. RIP Michael, Christopher, and Stevie. I was the same exact age as the boys in 1993 when they were murdered.

Sadly I feel it is very clear what is going on here and who committed this horrendous crime. But because so many mistakes were made by so many people at the beginning, they are now petrified of the consequences!

Circuit Judge Tonya Alexander needs to lose her job. These three poor children were tortured from a monster who is still walking free. How can a person not allow further testing for a case that will definitely help find the murderer? Bring justice for these boys.

Having just watched Devil’s Knot, my entire opinion of the West Memphis Three has changed. When I first heard about the murders I thought that these three teens had to be “sick” to murder three EIGHT-year-old boys for no reason! I only learned through reading this story that there were bite marks that did not match the defendants and that one of the poor kids was castrated! Also, that the blood on the stepfather’s knife matched one of the kids! I am by no means a judge or an attorney…but these men DESERVE to have their lives given back to them at least financially for what they were put through! I am also confused as to why the black man at Bojangles was never found. I mean West Memphis is not that big! Neither is Arkansas for that matter! Give these men the justice they deserve.

Why didn’t they check into the black man at the Bojangles restaurant who was covered in mud and blood to see if there was any connection between Mark Terry Hobbs and him? This is all so upsetting that this wasn’t followed up on, especially after the bite marks indicating that the three boys in prison didn’t match up. And the mysterious death of his wife.