calsfoundation@cals.org

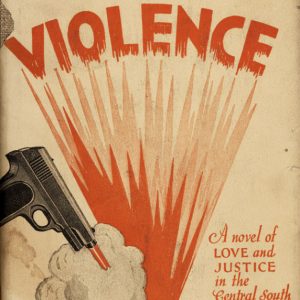

Violence: A Novel of Love and Justice in the Central South

In 1929, Simon and Schuster published Violence: A Novel of Love and Justice in the Central South by authors Marcet and Emanuel Haldeman-Julius. The novel’s plot is based on two real-life incidents. The first was the 1926 murder of a man in a church office by larger-than-life Baptist preacher J. Frank Norris of Fort Worth, Texas, and the second was the 1927 lynching of John Carter in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and the later execution of Lonnie Dixon.

Co-authors Marcet Haldeman and Emanuel Julius had married in 1916. They combined their surnames to demonstrate equality, at the suggestion of Marcet’s aunt, the famous Jane Addams. Like the eponymous publishing house they set up and ran in Girard, Kansas, they were politically and socially progressive. The Haldeman-Julius Company produced the Big and Little Blue Books series, as well as weekly and monthly magazines, for which Marcet wrote about both the J. Frank Norris trial and the John Carter lynching.

Norris was a notorious Southern Baptist preacher who was instrumental in founding what became Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth. When Norris preached against city officials proposing to tax a money-making business on church property, a friend of the officials showed up at the church office, and he and Norris argued. Later claiming self-defense, the preacher Norris shot and killed his visitor; he was later acquitted of the crime.

A few months later, Marcet traveled to Little Rock to report on events there. A white girl named Floella McDonald (described as anywhere between eleven and thirteen years old) had disappeared during the Flood of 1927. The discovery of her body in a church belfry by janitor Frank Dixon led to the arrest and indictment of his sixteen-year-old son Lonnie Dixon, who was Black, on charges of rape and murder. A few days later, on May 4, 1927, a Black man named John Carter was reported to have accosted a white woman and her teenage daughter on the outskirts of the city. A mob hanged him from a telephone pole, riddled his body with bullets, then dragged the corpse—in a winding procession of cars that stretched for twenty-six blocks—to Broadway and West Ninth Street, where they set fire to the body and rioted for hours before being stopped by the National Guard. Lonnie Dixon was later convicted of murdering Floella McDonald and died in the electric chair on June 24, 1927, his seventeenth birthday.

The fictionalized setting for Violence is “the beautiful State of Texlarkana” located between Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma. Even the fictional city—Rockworth—draws its name from the two locations that provided the basis for the plot. The J. Frank Norris character, Phil Jordan, is pastor of a church where a janitor finds the body of a fourteen-year-old white girl in the belfry and calls the police. After a prolonged and threatening interrogation, the janitor’s teenage son, Skip, confesses and is taken out of town, while mobs gather, unhampered by law enforcement. The city of Rockworth calms down for a day, but the next morning an all-day search ensues for a Black man, Mose, who allegedly accosted a white mother and daughter. The search ends with a lynching on a country road, a procession to the heart of the Black business district, and a riotous bonfire quelled when the governor calls the militia. Throughout the novel, the Northern-born wife of the preacher provides a running, moral commentary; she is horrified by the widespread assumption that the janitor’s son deserves to die and shocks her husband by comparing the young man’s actions to his own.

In a marked departure from Marcet’s reporting, the novel is rife with sexual affairs among the adults, both Black and white. The year before, Emanuel Haldeman-Julius had noted vigorous sales of Little Blue Books that addressed sexual behavior and health. The novel includes the sexual awakening of teen characters, who set up the church belfry as a retreat for their trysts, where the teenage girl had not been entirely averse to an encounter with the janitor’s handsome son. In the belfry, the fictional young man panics when the girl threatens to tell her father what they have just done. Without thinking, he hits her with a nearby brick, killing her, and starts trembling when he realizes that she is dead.

The book’s overarching message is the uneven justice system that acquits a prominent white man for reacting in haste to perceived danger but punishes a Black teen for the same act. After a bungled trial, a jury quickly convicts the novel’s teenager. Young Skip is attended at the execution by the preacher. As Skip dies, the preacher recognizes the inequity: “Sweepingly, convincingly, he was aware that Skip was no more deserving of what was about to happen than was he, Phil Jordan. But prejudice, the very sort of prejudice and passionate creed of violence that had saved him from punishment, was relentlessly putting this boy to death.”

Unfortunately for the co-authors—and for the five-year-old Simon and Schuster publisher—the book was a commercial flop. Reviews in both the New York Times and New York World point out the authors’ intent to indict the local culture. As the Times noted, “The Haldeman-Juliuses illustrate their case against the senseless violence of mob rule, against a section of the country which orders its affairs and administers its justice in a manner that the rest of the nation deems uncivilized.” The New York World stated, “The study of social psychology of the lynching is well done. But as a novel the book has many obvious defects. The greatest flaw is that the cards are too obviously stacked to work out an indictment of the society in which the events recounted happened.” Multiple reviewers assumed the Haldeman-Juliuses conveniently invented the complicated sequence of what happened in Little Rock, despite the fact that the Carter lynching had made national news only two years earlier. Even the 2019 article “Shame of the Southland: Violence and the Selling of the Visceral South,” published by the University of Mississippi’s Center for the Study of Southern Culture, called the lynching “the second of their invented stories,” a deus ex machina that was invented solely to drive home the point of Jim Crow injustice. However, one paper—the Chicago Defender—made the connection, no doubt because it had been barred from distributing in Little Rock for two weeks after the lynching, and reported that the associated editor of the Little Rock Survey had been forced to flee the state due to a death threat over his reporting about the lynching.

For additional information:

Gardner, Sarah E. “Shame of the Southland: Violence and the Selling of the Visceral South.” Study the South, January 29, 2019. https://southernstudies.olemiss.edu/study-the-south/violence/ (accessed July 3, 2024).

Haldeman-Julius, E. The First 100 Million. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1928.

Haldeman-Julius, Marcet. “The Story of a Lynching: An Exploration of Southern Psychology.” Haldeman-Julius Monthly 6 (August 1927): 3–32, 97–103.

———. The Story of a Lynching: An Exploration of Southern Psychology. Little Blue Book No. 1260. Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius. Girard, KS: Haldeman-Julius Publications, 1927.

Haldeman-Julius, Marcet, and Emanuel Haldeman-Julius. Violence: A Novel of Love and Justice in the Central South. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1929.

Harp, Stephanie. “Stories of a Lynching: Accounts of John Carter, 1927.” In Bullets and Fire: Lynching and Authority in Arkansas, 1840–1950, edited by Guy Lancaster. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018. Online at https://www.ncis.org/sites/default/files/TIS%20Vol.6%20Feb2020_EISENSTEIN2019_HARP_STORIES%20OF%20A%20LYNCHING_ACCOUNTS%20OF%20JOHN%20CARTER%201927.pdf (accessed July 3, 2024).

Hartley, C. “Violence.” New York World, November 17, 1929, p.11M.

Jones, Dewey R. “Dixie: There She Stands!” Chicago Defender (National Edition), November 2, 1929, p. 13.

“Mob Drives Editor out of Arkansas.” Chicago Defender, May 21, 1927, p. 1.

Mordell, Albert, compiler. The World of Haldeman-Julius. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1960.

“A Propagandist Novel.” New York Times Book Review, December 8, 1929, p. 9.

“Special Issue: The Haldeman-Julius Little Blue Books at 100.” Midwest Quarterly 61 (Fall 2019).

“‘University in Print’: Girard’s Little Blue Books.” Reflections 8 (Summer 2014): 6–9. Online at https://www.kshs.org/publicat/reflections/pdfs/2014summer.pdf (accessed July 3, 2024).

Stephanie Harp

Bangor, Maine

Fabulous description of the history that set the stage for the book Violence. Thank you!