calsfoundation@cals.org

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

aka: UALR

aka: UA Little Rock

University of Arkansas at Little Rock is a member of the University of Arkansas System, which includes four other major campuses and the Clinton School of Public Service. UALR began in 1927 as Little Rock Junior College (LRJC), housed in the Little Rock High School Building (later Central High School) under the administration of the Little Rock School Board. It became Little Rock University (LRU) in 1957 and moved to University Avenue. LRU became the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR) after it merged with the University of Arkansas system in 1969. In January 2017, the chancellor announced that the shortened form of the school’s name would be UA Little Rock rather than UALR.

The university is a metropolitan university that serves non-traditional students, many from families new to higher education. Starting with a group of about 100 students in 1927, the school had 13,119 full- and part-time students by September 2011. By 2023, however, enrollment was 7,147.

Particularly after 1969, the university has been uniquely committed to working with governmental, cultural, and business organizations in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and central Arkansas.

Founding and the Donaghey Foundation

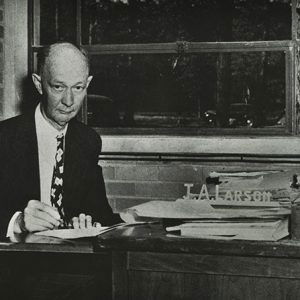

John A. Larson, then principal of Little Rock High School, founded LRJC after the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) stopped offering lower-division extension courses in Little Rock. The school district agreed to provide high school classrooms at no charge with the provision that tuition would pay for teacher salaries and classroom maintenance.

In 1929, former governor George W. Donaghey and his wife, Louvenia Wallace Donaghey, created an independent foundation whose sole purpose was to support LRJC. While Donaghey, who served as governor from 1909 to 1913, had little formal college training, he was a strong advocate for education. Income for the foundation first came from the Donaghey Building, which he had donated to the foundation. The Board of the Foundation is composed of Little Rock business leaders who manage the foundation’s assets. In the case of the Donaghey Foundation, the board determines the amount of money that it will give to the college based on income from its assets.

Later, Donaghey donated other Little Rock properties in 1937 for the foundation to manage. The 1929 bequest was the largest in Arkansas history up to that time. He later wrote, “I was convinced that no greater field for educational development exists anywhere than can be found right here in Little Rock.” On several occasions, Donaghey expressed the hope that LRJC would become a four-year school. For the next forty years, the foundation contributed to operational funding, but after the school joined the UA system in 1969, the foundation supported only special projects.

Growth and Change

In 1929, the school was fully accredited by the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, and enrollment reached 347 students. In 1931, LRJC moved to the former U. M. Rose Elementary School at 13th and State streets in Little Rock. The wave of World War II veterans, coming to LRJC under the GI Bill, forced the Little Rock School Board to seek a larger campus. By 1946, enrollment had reached 800 students, and it grew to 1,350 by 1951. In 1947, prominent Little Rock businessman Raymond Rebsamen donated eighty acres on the east side of Hayes Street, now University Avenue. Initially, temporary surplus buildings from World War II were used on the new campus, but in 1948, a “Permanent Home Campaign” began to solicit funds for new buildings.

After a successful community effort that brought corporations, alumni, and private citizens together, the board built four buildings designed by the Cromwell architectural firm. President John A. Larson, who had resigned his position as principal at Central High School to devote his full energies to LRJC, died in 1949, and the new library was named in his honor. Granville D. Davis, a member of the first LRJC graduating class, served as president from 1950 until 1954. In 1949, the football team, coached by Jimmy Karam, won the Junior Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California.

Early in the 1950s, interest in making LRJC a four-year institution grew. In 1954, the Little Rock School Board officially endorsed the concept, but the trustees of the Donaghey Foundation resisted any deviation from a junior college model and withheld funding. After a year of legal wrangling, the Arkansas Supreme Court ruled that the foundation could not arbitrarily withhold funds from the college. The two boards jointly appointed Little Rock business leader Gus Ottenheimer to chair a task force to study the potential for a four-year school, including affiliation with the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. In May 1956, the committee delivered its report recommending the creation of a four-year school regardless of UA support.

Under the leadership of the new president, Carey V. Stabler, LRJC became Little Rock University in the fall of 1957. Two years later, the Little Rock School Board withdrew administrative responsibility for the campus and transferred its role to a new nine-member panel, as the Ottenheimer Committee had recommended in its report. Course offerings grew from about eighty in 1956 to about 500 by 1967. As a private university, however, it was dependant on federal grants and private funding to keep tuition rates low, but at the same time, it was under pressure to expand the campus physical plant and to offer graduate programs. The North Central Association also urged the administration to enlarge the number of faculty members who held doctorate degrees and to increase the library’s holdings.

UALR and UA

During the mid-1960s, negotiations began anew to merge LRU with UA. Despite opposition from existing state-supported colleges that argued that educational programs would be duplicated, as well as skepticism from students who feared loss of the Little Rock identity, Governor Winthrop Rockefeller signed the bill merging LRU with the UA system in 1969. At the time, it offered twenty-eight undergraduate programs, listed about eighty faculty members, and had an enrollment of 3,500 students. Ten years later, the university offered seventy-three degree programs, including fourteen graduate programs, and enrolled 9,652 students.

Chancellor G. Robert Ross, who followed after Stabler’s 1972 resignation, was perhaps most responsible for leading this transition. Over time, UALR developed a law school, a graduate school that included accredited programs in social work and communicative disorders, and the Graduate Institute of Technology. In addition, other basic questions, which had not arisen during the LRJC and LRU years, were recognized, if not resolved, during the Ross years. These issues included faculty governance, academic freedom, and faculty research responsibilities.

All of these issues were part of the high-profile case involving Grant Cooper, who had been hired as an assistant professor of history in 1970 after earning a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania. Cooper’s father, a prominent physician and former chairman of the Little Rock School Board, had donated about $250,000 to LRU. Problems arose, however, during the summer of 1973 when Cooper announced that he was a communist. Although he had not formally joined the party, he told students that he interpreted history from the perspective of economic class, and he distributed literature from the Progressive Labor Party.

Cooper’s admission drew unfavorable attention to the university through articles in the Arkansas Gazette and, eventually, demands for his dismissal from members of the state legislature. Bedford K. Hadley, chairman of the Division of Social Sciences, issued a letter of non-reappointment to Cooper on the basis of poor classroom performance and lack of publications. In a responding lawsuit, Cooper’s attorneys argued that there were no systematic measures for review of faculty teaching and research. While Cooper left the UALR faculty, the lawsuit was not resolved until 1980. By that time, many departments on campus had developed written department by-laws and guidelines for faculty review, thus raising the level of faculty professionalism.

Ross also fought for UALR’s place in the UA system. Fayetteville Chancellor James E. Martin, who also served as president of the system at the time, objected to the way Ross lobbied in the legislature and went outside UA rules for procurement by making purchases without consultation. Eventually, Ross was fired by the University of Arkansas Trustees, even though Ross had strong support from the faculty, students, local leaders, and Donaghey Foundation members. Through the confrontation with Martin, Ross helped establish the clear autonomy of UALR.

In the Modern Age

Ross was succeeded by James H. Young, who served from 1982 until 1992. Unlike his predecessor, Young placed much stronger emphasis on the traditional liberal arts and established campus-wide learning goals as recommended by a blue-ribbon committee. Under his leadership, UALR built the school’s first residential dormitory. Charles Hathaway, who followed Young and served from 1993 to 2002, led the university back to an urban/metropolitan model based on sound financial planning. Hathaway also recognized the importance of technology by creating the new Cyber College in 1998 with funds from the legislature, foundations, and corporations such as Alltel and Acxiom. Joel E. Anderson followed Hathaway in 2003. Anderson focused on expansion of the campus itself, including the construction of the Stephens Events Center north of 28th Street and the purchase of the University Plaza, a shopping center that faces Asher Avenue. The plaza currently houses UALR’s National Public Radio (NPR) affiliate offices and the art department’s Applied Studio of Woodworking, and plans are in the works to move more offices to that location. Anderson retired in 2016, and Andrew Rogerson was announced as his replacement.

As a metropolitan university, the school has not developed traditions, in sports and mascots, in the way traditional residential schools have. Under Title IX rules, sports at UALR, except for men’s basketball and baseball, have changed over time. The UA Little Rock Hall of Fame was established in 1991 to honor not only players and coaches but also important supporters of university athletics.

UALR began the twenty-first century with 105 degree programs, including fifty bachelor’s, thirty-five master’s, and four doctoral. In 1975, the state legislature authorized a law school where students could earn a law degree and sit for the state bar exam, and thus was UALR’s Bowen School of Law established. The profile of the typical student has evolved as well—now more than sixty percent are female, and more than thirty percent are African American. The university plays a leading role in the Clinton School of Public Service on the Clinton Presidential Library campus in downtown Little Rock.

On May 2, 2012, UALR dedicated its new $15 million nanotechnology center, the UALR Center for Integrative Nanotechnology Sciences, to facilitate collaboration among researchers at UALR, the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS), and UA, and as well as with the Food and Drug Administration’s National Center for Toxicological Research in Jefferson (Jefferson County). The following year, UALR opened the George W. Donaghey Emerging Analytics Center, with the aim of providing visual data services for regional institutions.

In August 2019, Andrew Rogerson stepped down from the position of chancellor following a tenure that had seen enrollment decline, budgets cut, and increasing student dissatisfaction with the presence of an eStem charter school (and its high school students) on campus. He was replaced by Christina Drale.

In November 2023, UA Little Rock announced a new “$0 tuition” scholarship called the Trojan Guarantee for full-time first-year students who qualify for Pell grants and who receive the Arkansas Academic Challenge Scholarship. UA Little Rock’s fall 2023 enrollment was 7,147, and it has remained steady in subsequent years.

For additional information:

Ledbetter, Calvin R., Jr. Carpenter from Conway: George Washington Donaghey as Governor of Arkansas 1901–1913. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Lester, Jim. The People’s College: Little Rock Junior College and Little Rock University, 1927–1969. Little Rock: August House Publishing, 1987.

———. “The People’s University II.” Unpublished manuscript. Ottenheimer Library Archives and Special Collections. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Lewis, Johanna Miller, Stephen L. Recken, et al. “‘Giving All He Had to Education:’ A History of the George W. Donaghey Foundation, 1929–1999.” Unpublished manuscript. Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Martin, Richard. “Fast Times at Pine Tree High.” Arkansas Times, August 20, 1992, pp. 18–21.

Recken, Stephen L. “Evolving Identity: LRJC to UALR, 1927–1969.” Pulaski County Historical Review 55 (Spring 2007): 13–23.

University of Arkansas at Little Rock. http://www.ualr.edu (accessed September 12, 2024).

Stephen L. Recken

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.