calsfoundation@cals.org

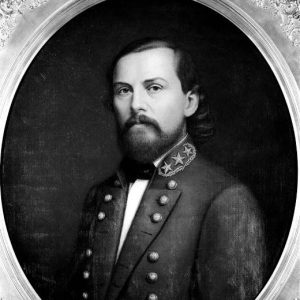

Thomas Carmichael Hindman (1828–1868)

Thomas Carmichael Hindman was a prominent attorney and Democratic politician prior to the Civil War. In the crisis prior to that war, he was a major player in bringing about the state’s secession. He subsequently served in the Confederate army as a brigadier general, playing a prominent role in the defense of Arkansas and later serving in the Army of Tennessee.

Thomas Hindman was born on January 28, 1828, at Knoxville, Tennessee, one of Thomas Hindman and Sallie Holt Hindman’s six children. His father was a planter and a federal agent for Indian affairs in Tennessee. In 1841, his father purchased a new plantation in Ripley, Mississippi, and the family moved there. Hindman went to local schools, and then, like the children of many prominent Southern planters, he went east to study at the Classical Institute in Lawrenceville, New Jersey.

Hindman demonstrated his aggressive and militant spirit early in life. In 1846, he joined the Second Mississippi Volunteer Infantry that had been organized to fight in the Mexican War. He found little opportunity to realize his military ambitions, however. His unit was assigned to garrison duty at Monterrey, and his writing skills led to his appointment as the regiment’s adjutant. By the war’s end, he had been promoted to the rank of lieutenant. After the war, he returned to Ripley, where he passed the bar exam and began a career as a lawyer. He also became involved in politics, linking himself with the Democratic Party, and was elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives in 1853. Contemporary politics often involved personal slurs, and in his early career, Hindman showed himself willing to defend his honor in fights or on the dueling field.

Seeking new opportunities, Hindman moved to Arkansas in 1854, settling in Helena (Phillips County), where he opened a law office; an advertisement for his practice appeared in the Southern Shield of September 30, 1854. His legal practice languished because he quickly became involved in local politics and devoted much of his time there. His marriage to Mary Watkins Biscoe, daughter of wealthy planter Henry L. Biscoe, in 1857 left him well off financially and furthered his political opportunities. The couple had five children. At Helena, Hindman established a close friendship with future Confederate general Patrick Cleburne. The two were law partners for a time and engaged in numerous business activities together.

In the 1856 general election, Hindman actively campaigned for Democratic candidates and became well known for his stump speeches. Despite being a relative newcomer on the political scene, he successfully ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1858. He was reelected in 1860. His 1860 platform had argued that the abolitionist North threatened the rights of the Southern states and that secession was the only way to protect Southern property.

As he secured political office, Hindman discovered that the dominant state Democratic faction known as “The Family” stood in the way of his ambitions. In 1858, he wanted the seat in the United States Senate held by William Sebastian when the incumbent came up for reelection. Democratic leaders endorsed Sebastian rather than Hindman, leading Hindman to establish his own newspaper at Little Rock (Pulaski County), the Old Line Democrat, in opposition to the Family’s True Democrat. Hindman’s alienation developed further when Governor Elias N. Conway, one of the Family’s leaders, sought to settle the state’s banking question by initiating a plan that would have seized the assets of those indebted to the bank, including Hindman’s father-in-law. By 1860, Hindman had established himself as an independent political force in the state and helped secure the election of Henry M. Rector over the Family candidate, Richard H. Johnson, brother of Senator Robert Ward Johnson and editor of the True Democrat, in the race for governor.

Following the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln to the presidency in 1860, Hindman made peace with the leader of the Family, Senator Robert Ward Johnson, and turned to what he considered the more immediate problem of the state’s place in a country dominated by a Republican president. Hindman did not believe Arkansas could remain safely in the Union and joined with Johnson in urging the governor and the legislature to call a state convention to secede. Arkansas responded slowly to the call for secession, however. Hindman campaigned to urge the state convention to act but could accomplish nothing until after the Battle of Fort Sumter. In the wake of his home state’s secession, Hindman resigned from the U.S. Congress. He hoped to be named to the Confederate Congress, but the state legislature failed to name him to that body. He then helped raise a regiment that became the Second Arkansas Infantry and secured appointment as its colonel.

By September 1861, he had received a promotion to the rank of brigadier general and assumed command of a brigade in the Army of Mississippi at Corinth. He served at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6–7, 1862. He escaped from the battle with minor wounds sustained when an artillery shell struck his horse. A week after that battle, the Confederate government promoted Hindman to the rank of major general. In May 1862, it sent him to Arkansas to command the Trans-Mississippi Department, a new military district that was threatened by a Union invasion force under General Samuel R. Curtis. Curtis’s army had moved from Missouri down the White River and, because few Confederate troops remained in the state, possessed a virtually clear road to capture Little Rock.

Hindman’s primary job was to stop Curtis, and he aggressively recruited men and equipment to halt the Union troops. As part of his efforts, he also declared martial law and ordered the army to burn all cotton that the enemy threatened to seize. Curtis failed to secure supplies due to low water on the White River and so abandoned his march on the capital city, moving instead to Helena on the Mississippi River. Hindman took credit for saving Arkansas, although Curtis’s retreat had little to do with Hindman’s efforts. Despite Hindman’s success, his efforts gave rise to serious opposition from civilians and two of his commanders, Generals Albert Pike and Douglas H. Cooper. All complained vigorously to Confederate authorities that Hindman had acted unconstitutionally in his actions. The Confederate government at Richmond, Virginia, succumbed to pressure and replaced him as commander of the Trans-Mississippi District with General Theophilus Holmes. Although now under Holmes’s command, Hindman remained in charge of the District of Arkansas and retained active command of the military force with the state.

In the autumn of 1862, Hindman led his force into northwestern Arkansas in an effort to drive out Union forces that had occupied the area. On December 7, 1862, he engaged Union forces under Generals James G. Blunt and Francis J. Herron at the Battle of Prairie Grove. The battle did not, however, produce a decisive victory for either side. Although a tactical draw, the battle turned into a strategic defeat when Hindman, unable to continue fighting because of his inability to re-supply his troops, had to withdraw to the Arkansas River. His poorly fed and supplied army broke up on its retreat, leaving the northwestern part of the state virtually undefended. Hindman returned to Little Rock, where he asked to be reassigned to another army. Richmond authorities complied, removing him from command in the District of Arkansas. He received a temporary assignment to a court of inquiry in Mississippi.

In July 1863, Hindman regained an active command when appointed to a division in the Army of Tennessee at Chattanooga. He entered an army with an officer corps seriously divided, and he did little for his career when he linked himself with the faction of General William J. Hardee against the commander of the army, General Braxton Bragg. Two disabling wounds also plagued him. The first came at the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863, although he returned to his division just in time for the Confederate loss in the Battle of Chattanooga on November 24–25, 1863. In the Atlanta campaign, he received a wound at Kennesaw Mountain, on June 27, 1864, that left him partially blinded. At this time, he left his command for a final time and joined his family in Texas, to where they had moved following the Union occupation of the eastern part of Arkansas.

In June 1866, unable to secure a pardon from President Andrew Johnson and indicted by a federal district court in Arkansas for his activities during the war, Hindman and his family moved to Mexico. He initially sought to practice law in Mexico City but then joined other Confederate refugees at the town of Carolota, where he again tried to practice law and also engaged in coffee planting. Conditions in Mexico were unfavorable to Hindman’s efforts, and in 1867, he returned to Helena. His combative spirit quickly embroiled him in Reconstruction politics. In the 1868 election, he urged conservatives to take the oath of allegiance so that they could vote against Republican candidates. He was unique among conservatives, however, in encouraging acceptance of African American suffrage and organization of black voters into support of the conservative cause.

On September 28, 1868, an assassin fatally shot him through a window at his home. Law officials never arrested anyone for the act. The motive of the killer was never determined, although political opponents, personal grudges, and even domestic problems were among the reasons considered. He is buried at Maple Hill Cemetery in Helena.

For additional information:

Nash, Charles E. Biographical Sketches of Gen. Pat Cleburne and T. C. Hindman. Little Rock: Tunnah & Pittard, 1893.

Neal, Diane, and Thomas W. Kremm. Lion of the South: General Thomas C. Hindman. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1993.

Roberts, Bobby L. “General T. C. Hindman and the Trans-Mississippi District.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Winter 1973): 297–311.

———. “Thomas C. Hindman, Jr.: Secessionist and Confederate General.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, 1972.

Carl H. Moneyhon

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.