calsfoundation@cals.org

Stone County Lynching of 1898

A possible lynching occurred in rural Stone County in March 1898. While state and national reports differ as to the likely fate of the victim, both confirm that the unnamed “negro boy” in question was repeatedly tortured by a mob.

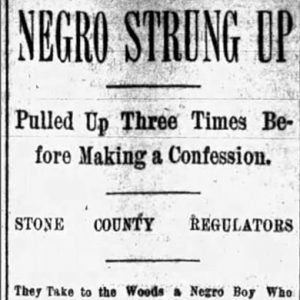

On March 18, 1898, the Kansas City Journal reported, under the headline “Arkansas Negro Boy Lynched,” the following: “A negro boy whose name cannot be learned was lynched at Marcella, in Stone County, Tuesday night March 15. He was accused of stealing $20 from the cash drawer of a store. The mob strung him up three times in an effort to make him confess and finally left him on the ground in a dying condition.” The Arkansas Gazette contains a much more detailed narrative that, on a few small points, contradicts the nationally circulating report, despite both being datelined “Batesville, March 17.” The Gazette, for one, has this action occurring on Saturday, March 12, rather than Tuesday, March 15. It does not specify the amount of money taken, only reporting: “Some days ago the cash drawer in the store of a merchant named Casey was robbed of a small amount of money.” The “negro boy” at the center of this drama remains unnamed, save that he was “employed by Mr. Hess.” This may have been either Thomas M. Hess, a grocer listed as sixty-five years old on the 1900 census, or his son Thomas E. Hess, a twenty-seven-year-old merchant; both lived in Wallace township where Marcella is located.

The Kansas City Journal describes the affair as a lynching, a word connoting (at this time) a definite lethality, even though its narrative does not have the unnamed boy dead at the end but only “in a dying condition.” However, the Gazette, while going into greater detail about the tortures inflicted upon this unnamed boy, would seem to deny it the title of lynching. According to the Gazette, on Saturday night, “a band of about twenty-five regulators took the boy into the woods and tried to force him to tell where the money was.” Upon his denial of the theft, “the mob put a halter around his neck and swung him up to a limb.” Before he was completely strangled, the mob let him down, but the boy “refused to acknowledge his guilt and the mob swung him up again.” After this second round, he still refused to confess, and so he was subjected to a third round of torture: “With the boy’s body dangling in the air, covered with blood which flowed in streams from wounds in his neck caused by the terrible jerking of the rope, the mob pointed their guns at the half dead negro and the leader shouted to him that he would be given just three seconds to confess and that if a sign were not forthcoming when he counted three every gun in the crowd would be discharged into his body.” After the count of two, the boy “made the sign indicating that he was ready to confess” and was thus let down, upon which he confessed “in an incoherent manner.” The report ends thusly: “The mob, satisfied of the negro’s guilt, decided that he had been punished enough, and dispersed leaving their victim to take care of himself. He will probably recover.”

There were no follow-up reports on the fate of this boy. Because the victim was never named, it remains impossible to check conventional records to learn how this attack might have affected the boy’s future. However, this event does appear on most tabulations on lynching in the United States, and the nature of the violence certainly places it at least on the same continuum as lynching.

For additional information:

“Arkansas Negro Boy Lynched.” Kansas City Journal, March 18, 1898, p. 6.

Lancaster, Guy. “Lynching and the Limits of History: An Essay on Epistemic Uncertainty.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 81 (Spring 2022): 1–18.

“Negro Strung Up.” Arkansas Gazette, March 18, 1898, p. 3.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Stone County Lynching Article

Stone County Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.