calsfoundation@cals.org

Poll Tax

A poll tax is a uniform per capita tax levied upon a specified class of people often made a requirement for the right to vote. In Arkansas, use of a poll tax was as old as the state itself. Arkansas’s first state constitution, adopted in 1836, authorized the imposition of poll taxes to be used for county purposes, and a subsequent state statute authorized county courts to collect a poll tax not to exceed one dollar per year from every free male inhabitant between the ages of twenty-one and sixty. Provisions similar to that in the 1836 constitution were included in the subsequent Confederate state constitution of 1861 and Unionist state constitution of 1864 (the Confederate constitution allowed the poll tax to be used for corporation as well as county purposes).

With the launching of congressional Reconstruction after the Civil War, yet another state constitution was written, that of 1868. Reflecting the more democratic spirit of the convention that authored it, and recognizing that a poll tax was an inherently regressive tax that fell most heavily upon the poor, the 1868 constitution declared, “The levying of taxes by the poll is grievous and oppressive; therefore the general assembly shall never levy a poll tax excepting for school purposes.” Another section of the document mandated the annual collection of a one-dollar head tax from every male inhabitant over the age of twenty-one but specified that the monies raised could only be used to support a new system of free public schools.

At the end of the Reconstruction era, a fifth constitution was adopted in 1874, the one under which Arkansas still operates. It retained the poll tax provisions of the 1868 organic law, also assessing a per capita tax of one dollar per year on every male inhabitant over the age of twenty-one, with the monies collected to be placed in the state’s public school fund. In part, this was done out of a professed recognition that since universal suffrage was now a reality for both black and white men, there was a need for public schools to help create an informed and educated electorate.

Collection of the poll tax had proven difficult, nevertheless, and payment had been at best sporadic, a state of affairs that sometimes produced disgruntlement among the wealthy; taxes on real and personal property, which the wealthy disproportionately owned, became the principal source of state revenues.

Eventually, the beginning of the agrarian revolt in Arkansas during the late nineteenth century would result in new efforts to collect the poll tax. Angry at the failure of the state’s dominant Democratic Party to provide any meaningful economic relief in the depressed post–Civil War years, thousands of yeoman farmers began to “kick over the traces” and join new third-party agrarian insurgencies, acting first in 1888 and 1890 through the Union Labor Party and later, beginning in 1892, through the Populist or People’s Party. When Arkansas Republicans, half of whom at the time were African American, endorsed the Union Labor nominees for state office in 1888 and 1890, the effect was to create something largely unprecedented in Arkansas—a biracial coalition of poor blacks and poor whites.

Democratic chieftains and conservative elites moved swiftly to deflect this threat. One method of doing so was to restrict third-party agrarians’ and Republicans’ access to the ballot box. In 1891, the Arkansas General Assembly adopted a new state election law that effectively gave state Democrats control over the appointment of voting officials in every county in Arkansas and excluded thousands of illiterates from participating in elections. The same legislature also proposed a new poll tax amendment to Arkansas’s constitution.

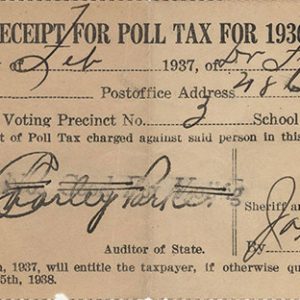

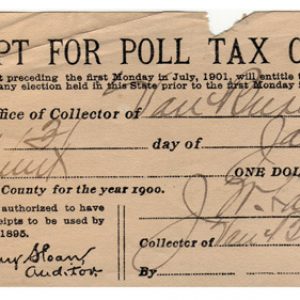

Under the proposed new amendment, before prospective voters could be given a ballot, they would be required to present an official receipt at the polling places attesting to the fact that they had paid their current annual poll tax. The poll taxes had to be paid and the receipts had to be obtained, not at the county clerk’s office or the county treasurer’s office, but rather at the county sheriff’s office; this, no doubt, was intimidating to many people. For those voters who did pay the poll tax, precinct officials on election day were instructed to stamp or initial their poll tax receipts before returning them to the voters. It was hoped that this procedure would stop unscrupulous “repeating” or multiple voting, a practice claimed by whites to be commonplace among African Americans, since black people all supposedly “looked alike.” Another feature of the amendment withheld the ballot from convicted felons.

After being proposed by the legislature, the poll tax amendment was submitted to the people for approval in the September 1892 state election. Occasionally, Democratic proponents openly invoked race and disfranchisement of African Americans as a reason for supporting the measure, though supporters more often stressed that the one-dollar fee would be affordable for anyone. (However, in an era in which a dollar a day was a commonplace wage for workers, the poll tax was, for many, a formidable barrier to inclusion in the democratic process.) Most frequently, though, advocates advanced the poll tax as a means of raising additional revenues for the public school system.

Despite the incessant Republican and third-party attacks against the measure, some election returns suggest that numbers of African Americans did vote for the poll tax. One explanation is the not-too-veiled threat from some whites to slash funding for black education if the tax were defeated. However, the election in which the poll tax amendment was voted upon was the first major election conducted under the new Election Law of 1891, which gave the Arkansas Democratic Party practical control over every voting precinct in Arkansas. Fraud and the deliberate miscounting of ballots are the most obvious explanations for seeming black support for the poll tax amendment.

Even with assistance of the new voting law, it was highly doubtful that the poll tax proposition had carried. It received a plurality but not an absolute majority of all the votes cast in the election; some 23,750 people chose not to cast votes on the amendment at all. Although the state constitution clearly mandated that a proposed constitutional amendment had to be approved by a majority of those voting in an election, the Democratic-controlled legislature nonetheless declared that the poll tax amendment had been approved, and it took effect after April 14, 1893.

Nevertheless, complaints about Amendment 2’s questionable ratification persisted for years. Finally, in a 1906 case contesting ratification of a different proposed constitutional amendment on similar grounds, the Arkansas Supreme Court in Rice v. Palmer ruled that ratification required the approval of a complete majority of all those taking part in the election in which the proposal had been voted upon. The Rice v. Palmer decision did not immediately overturn the original poll tax amendment, but it was clear that any lawsuit brought against it would be successful. Already, in fact, in the related 1905 case of Knight v. Shelton, Federal District judge Jacob Trieber had forbidden use of the poll tax as a voting requirement in Arkansas congressional elections, ruling that Amendment 2 had never been properly ratified.

Hoping to deflect further judicial assaults, the legislature submitted a second poll tax amendment, Amendment 9, to the voters in 1908. This second measure won approval by means as doubtful as the first. A voter had to possess a poll tax receipt before he could participate in the election and vote on the poll tax amendment. Under these circumstances, the new amendment received the necessary majority.

Together, the 1891 election law and the 1892 poll tax amendment had a revolutionary impact on Arkansas politics. There were 65,000 fewer voters in 1894 than in 1890, a drastic decline in turnout. The combined impact of both measures had by 1894 completely swept African Americans from the state legislature, as well as from most local and county offices (not until 1973 would African Americans again serve in the Arkansas General Assembly). The 1891 election law and the 1892 poll tax amendment also broke the back of the third-party agrarian insurgency and destroyed any hope that it might transform the lives of the state’s rural poor. Working in tandem, the measures established white supremacy and one-party rule as the central tenets of Arkansas society and politics for almost three-quarters of the next century.

Over time, legal requirements pertaining to the poll tax were elaborated upon and expanded. After the adoption of a women’s suffrage amendment to the state constitution in 1920, the Arkansas Supreme Court, in Taafe v. Sanderson (1927), invoked the privileges and immunities doctrine to hold that women over the age of twenty-one would also have to pay an annual poll tax in order to vote. In 1929, to encourage payment of the poll tax, the Arkansas General Assembly adopted a new law stating that no state employees or contractors could be recipients of public funds or recipients of state licenses or permits until they had paid their poll taxes.

Once in place, the poll tax and other disfranchisement measures, in addition to politically disempowering thousands of poor people, gradually began to have a broad social impact. Eliminating or drastically reducing black representation on local school boards caused funding for black schools to shrink precipitously. By 1930, the state was spending less than half as much per annum to educate a black schoolchild as a white schoolchild. Underfunded schools and unequal educational opportunities for blacks, in turn, lessened prospects for economic advancement and social mobility among African Americans.

The poll tax also fueled a pervasive climate of political corruption within Arkansas. Although prohibited by Act 123 of 1935, wholesale purchase of poll taxes by others not in the purchaser’s immediate family was widespread, and illegally obtained poll tax receipts were widely distributed by candidates to their supporters. No personal identification was required for applications for absentee ballots, and signatures on such applications were often forged; even many dead people lying in cemeteries evidently cast ballots. Legal requirements that poll tax receipts be stamped or initialed by election officials at the polls were routinely ignored, allowing some dishonest voters to “vote early and often” at different precincts on election day. Convinced that elections were often “rigged” in advance, even many of those Arkansans who could afford to pay poll taxes increasingly did not bother to vote, with election turn-outs steadily declining.

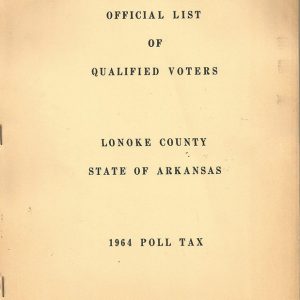

Disquiet and growing public alienation eventually gave rise to efforts to abolish the poll tax as a requirement for voting. Although a proposed state constitutional amendment to this effect was defeated in 1938, Governor Sid McMath attempted in vain to obtain its repeal following World War II. Success had to await the advent of the civil rights era of the 1960s. Only in November 1964 did Arkansas voters approve a new state constitutional amendment that replaced the poll tax with a modern voter registration system. Led by a Voter Registration Committee chaired by a white physician and civic leader from Arkadelphia (Clark County), Dr. H. D. (Dave) Luck, supporters of the new amendment included not only civil rights activists but such good-government advocates as the Arkansas units of the League of Women Voters, the American Association of University Women, the Business and Professional Women’s Association, and the Arkansas Education Association. They, in turn, were backed by the state’s two most important newspapers, the Arkansas Gazette and the Arkansas Democrat. Future Arkansas governor Winthrop Rockefeller, along with organized labor, provided important financial support for the repeal effort.

During the same year in which Arkansas repealed its poll tax, the Twenty-fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, prohibiting the use of the poll tax in congressional and presidential elections. Passage of the new Federal Voting Rights Act by Congress the following year and a 1966 decision of the U.S. Supreme Court, Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, extended this prohibition to all state and local elections throughout the nation.

For additional information:

Bayliss, Garland Erastus. “Public Affairs in Arkansas, 1874–1896.” PhD diss., University of Texas, 1972.

Branam, Chris M. “Another Look at Disfranchisement in Arkansas, 1888–1894.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 69 (Autumn 2010): 245–262.

Crawford, Sidney Robert. “The Poll Tax.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1944.

Fain, James Harris. “Political Disfranchisement of the Negro in Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1961.

Gordon, Fon Louise. Caste and Class: The Black Experience in Arkansas, 1880–1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995.

Glaze, Tom, with Ernie Dumas. Waiting for the Cemetery Vote: The Fight to Stop Election Fraud in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2011.

Graves, John William. “The Arkansas Negro and Segregation.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1967.

———. “Jim Crow in Arkansas: A Reconsideration of Urban Race Relations in the Post-Reconstruction South.” Journal of Southern History 55 (August 1989): 421–448.

———. “Negro Disfranchisement in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 36 (Autumn 1967): 199–225.

———. Town and Country: Race Relations in an Urban-Rural Context, Arkansas, 1865–1905. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Hawkins, Marlin, and C. Fred Williams. How I Stole Elections: The Autobiography of Sheriff Marlin Hawkins. Morrilton, AR: 1991.

Kousser, J. Morgan. The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, 1880–1910. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974.

Ledbetter, Calvin R., Jr. “Arkansas Amendment for Voter Registration without Poll Tax Payment.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 54 (Summer 1995): 134–162.

Moneyhon, Carl H. Arkansas and the New South, 1874–1929. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997

Ogden, Frederic. The Poll Tax in the South. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1958.

Perman, Michael. Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888–1908. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Segraves, Joe Tolbert. “Arkansas Politics, 1874–1918.” PhD diss., University of Kentucky, 1973.

Stockley, Grif. Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

John William Graves

Henderson State University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.