calsfoundation@cals.org

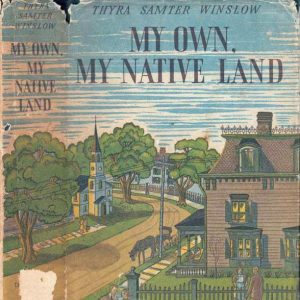

My Own, My Native Land

My Own, My Native Land, published in 1935, is an anthology of short stories by Thyra Samter Winslow, a native of Fort Smith (Sebastian County). In writing these stories, Winslow contributed significantly to the new wave of popular American magazines in the early twentieth century. These stories and sketches depict the mores of a small Southwestern town, likely modeled on Fort Smith, showing people preoccupied with social status and family pride.

The anthology contains forty pieces. Some appeared in The New Yorker under a heading that became the title of the collection. Others were first published in other magazines, especially Smart Set, a widely read publication subtitled, “A Magazine of Cleverness,” edited by H. L. Mencken and George-Jean Nathan. Winslow was a particular favorite of Mencken’s, as she shared his low opinion of America west of the Hudson River.

The stories in My Own, My Native Land are representative of Winslow’s work, depicting small towns and the women who belong to (or aspire to belong to) the upper social classes. These women want to marry well and to appear prosperous, socially prominent, and, especially, respectable. They consider the right clothes, a good address, and membership in the best company essential to attracting and keeping a husband. “The Girl Who Stayed at Home” and “Visiting Girl” present two approaches to this task.

The people in Winslow’s stories go to great lengths to preserve their status as “the best families.” In “Salt-Rising Bread,” the African American cook bakes bread and sells it door to door, providing the only income for two elderly impoverished sisters. In “Social Leaders,” the Platts, although as rich as the Donaldsons, must outdo them in lavish entertaining to preserve their status, because Mrs. Platt, before her marriage, had worked as a schoolteacher. Some stories recount the efforts of a “best family” to conceal or ignore a disabled or unsuccessful member, as in “Face at the Window.”

“The Best Man in Town” bitterly describes the rise and fall of Hugo Dahlmer. Notably, his story resembles that of Winslow’s father, Louis Samter, a German Jewish merchant in Fort Smith. Hugo Dahlmer rises to prominence in a small Southern town via hard work and excellent business sense. The Dahlmers are tolerated in society chiefly at fundraising entertainments. He generously mentors younger men starting businesses that actually compete with his own. When Mr. Dahlmer loses his money, his business, and his home, these men do nothing to help him. When he dies, people say, “Hugo Dahlmer, he was the best man in town.” And someone else adds, “And a lot of good it ever did him.”

Winslow’s authorial style in this collection reflects her early journalistic training. Like Ernest Hemingway, who also began a career as a newspaper writer, she reports an incident without authorial comment. Whereas Hemingway dramatizes a story with characterization and dialogue, Winslow gives an impersonal narrative account. The indifference and monotony of the narration underscore the limitations and superficiality of the society she depicts.

For additional information:

Simpson, Ethel C. “Thyra Samter Winslow’s Magazine Fiction.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Summer 2020): 116–132.

Winegard, Richard C. “Thyra Samter Winslow: A Critical Assessment.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 1971.

Winslow, Thyra Samter. My Own, My Native Land. New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1935.

Ethel C. Simpson

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Literature and Authors

Literature and Authors My Own, My Native Land

My Own, My Native Land

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.