calsfoundation@cals.org

Louis Thomas "Moondog" Hardin Jr. (1916–1999)

aka: Louis T. Hardin

Louis Thomas “Moondog” Hardin Jr. grew up and learned to play the piano in Independence County. He later became a musician and composer admired in jazz, classical, and rock circles. He was also known for living on Manhattan streets dressed as a Viking and banging a drum.

Louis Hardin was born on May 26, 1916, in Marysville, Kansas, the son of an Episcopal minister, Louis Thomas Hardin Sr., and Norma Alves, a homemaker and teacher. He had one sister and one brother. The family moved around the Midwest when he was young. Playing tom-tom at a Wyoming Arapaho dance at a young age fostered a life-long affection for Native American rhythms. As an adult, Hardin performed with the Blackfoot tribe.

While in Hurley, Missouri, in his early teens, he lost his sight while playing with a dynamite cap that exploded. Hardin went on to play drums in the Hurley school band, and he finished high school at the Iowa School for the Blind. In the early 1930s, the Hardins lived in St. Louis, Missouri, and Hardin attended the state blind school. In May 1936, Hardin’s father became rector of St. Paul’s in Batesville (Independence County). The family lived just east of Batesville in Moorefield (Independence County).

Hardin, who became known for wearing capes and having long hair, took piano lessons from area teacher Bess Maxfield. He attended Arkansas College (now Lyon College) for a year in 1936 and was in the college literary society. Hardin’s mother left soon after the move to Arkansas, and the Hardins divorced. Louis Hardin Sr. remarried, and because of this, had to leave the church. The family remained in the state for some years after.

In 1942, Hardin obtained a scholarship to study music in Memphis, Tennessee, with the head of the Memphis Conservatory of Music. The next year, he moved to New York City and managed to meet Arturo Toscanini and Leonard Bernstein, all while busking and selling broadsides and sheet music of his songs in the street. In 1947, following the dissolution of his marriage to Virginia Sledge, Hardin adopted the stage name Moondog after a moon-fixated canine he remembered from Missouri. His marriage to Mary Whiteing Hardin produced a daughter, June; Hardin later fathered another daughter, Lisa Colins, out of wedlock.

When pioneering 1950s Cleveland, Ohio, rock and roll disc jockey Alan Freed called his radio program The Moondog Rock and Roll Party, using Hardin’s song “Moondog Symphony” as background music, Hardin successfully sued Freed, with composer Igor Stravinsky testifying for Hardin.

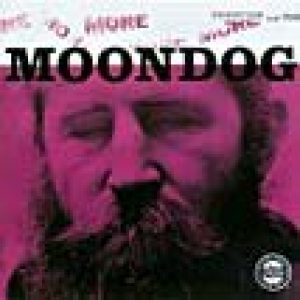

Hardin had released a few 78 rpm singles, and in 1953, his debut album, Moondog and Friends, was issued; six more albums were released through the late 1950s. Hardin’s music, which often consisted of poems spoken over jazzy rhythms and street noise, connected with Beat poets and others but not the mainstream. Hardin did not record again for a dozen years and then cut two albums for Columbia, shifting emphasis to his orchestral compositions and classical canons and rounds. He also did the arrangements for a Julie Andrews album of nursery rhymes.

Meanwhile, Hardin had become a decades-long fixture in Manhattan streets, appearing in a modification of the dress he debuted in north-central Arkansas—homemade Viking chic. He used an army blanket as a tunic and had a horned helmet, staff, and long beard. Hardin lived on the street to finance his composing but also had a primitive cabin upstate. Few passersby knew he was a composer.

In 1974, Hardin moved to West Germany and eventually settled in Oer Erkenschwick. Many New Yorkers thought the street musician known as “the Viking of Sixth Avenue” had died. Instead, he became better known and was able to record more in Europe.

Hardin wrote the liner notes to Big Band, his first release on his own Trimba label in 1995. For the song “You Have to Have Hope,” he wrote: “Bill Clinton lived in Hope, I lived in Batesville, Arkansas. We never met. I heard he played the sax, for which I wrote the piece he hasn’t heard, as yet. ‘Back in Arkansas’ are words that fit a falling bit of melody. I’m harking back sixty years to Batesville Bess and all she did for me,” referring to his early Arkansas piano teacher, Bess Maxfield.

Jazz, classical, and rock musicians alike played Hardin’s compositions. In the late 1960s, Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janis Joplin recorded Hardin’s “All Is Loneliness,” and Insect Trust, with Little Rock (Pulaski County) native Robert Palmer, covered Hardin’s “Be a Hobo” in 1970. A Moondog song was in the 1972 film Drive, He Said with Jack Nicholson, and Hardin was interviewed on TV’s Today and The Tonight Show.

In the 1980s and 1990s, musicians such as John Fahey, Kronos Quartet, and NRBQ recorded Hardin’s songs. By then, with his lengthy beard turned white, his reputation amongst musical tastemakers was indelible: he had invented several esoteric musical instruments (the oo, trimba, and ooo-ya-tsu), played with everyone from Charles Mingus to Philip Glass, and influenced the likes of Tom Waits. In 1997, Atlantic issued Sax Pax for a Sax, his first major U.S. release in more than twenty-five years—and his last.

Hardin died on September 8, 1999, in Munster, Germany. Hardin’s death was noted internationally, although his Arkansas roots were seldom mentioned. A few years later, a sampled version of his song “Bird’s Lament” was used in auto commercials. In September 2023, the album Songs and Symphoniques: The Music of Moondog was released, featuring various artists performing Moondog’s work.

For additional information:

Farber, Jim. “‘His Work Seems Endless’: Music Stars Pay Tribute to the Incredible Life of Moondog.” The Guardian, September 26, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2023/sep/26/moondog-eccentric-musician-songs-and-symphoniques (accessed September 26, 2023).

Hyde, Gene. “Iconoclastic New York Musician Had Arkansas Roots.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, March 17, 2000, p. 1E.

Koch, Stephen. “‘Moondog’ Hardin.” Arkansas Times, July 15, 2004, p. 20.

“Louis (Moondog) Hardin, 83, Musician, Dies.” New York Times, September 15, 1999. Online at http://www.nytimes.com/1999/09/12/nyregion/louis-moondog-hardin-83-musician-dies.html (accessed August 19, 2023).

Obituary of Louis (Moondog) Hardin. London Times, September 15, 1999.

Scotto, Robert. Moondog: The Viking of 6th Avenue. Los Angeles: PROCESS, 2007.

Stephen Koch

“Arkansongs”

Moondog Albums

Moondog Albums  "Moondog Monologue," Performed by Moondog

"Moondog Monologue," Performed by Moondog

From September 1969 through August 1970, I lived at 601 W. 113th Street in New York City. Moondog lived across the street. I’d leave my building early in the morning to catch the subway to W. 83rd Street, where I taught school. Moondog also took the subway downtown. I never knew where he was going. Nor did we ever speak. I only knew he was a city “character,” which was apparent since he’d have on a Viking helmet and carried a staff. I knew he stood on a corner somewhere and preached. Only now do I learn who this rare human being was and what his accomplishments were.