calsfoundation@cals.org

May Hearn (Lynching of)

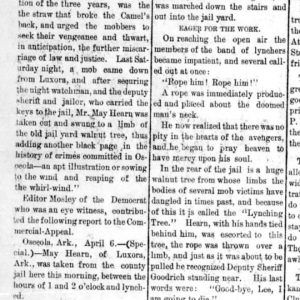

May Hearn, a young white man in his twenties and the son of a farmer in Luxora (Mississippi County), was lynched in Osceola (Mississippi County) on April 6, 1901, for shooting and killing Clyde King “at a place of bad repute” on the night of March 31, 1901.

The Arkansas Democrat noted that Hearn was the son of J. R. Hearn, “one of the most respected farmers living in the neighborhood of Luxora” and a longtime magistrate of the town. May Hearn, however, played the role of the wayward son; as the Osceola Times wrote: “When sober, May Hearn is said to be quiet and peaceable, but when under the influence of Luxora whiskey, all the treachery and blood-thirstiness of a cannibal seems to be aroused in him.” Indeed, even before the murder of King, Hearn had reportedly “shot at no less than seven individuals, and each time with no cause or provocation.” At the time he was lynched, he was out on bond pending appeal after having been sentenced to three years in the penitentiary for assaulting, with intent to kill, the town marshal at Luxora. He had been convicted in a previous assault but was ultimately pardoned by Governor Daniel Webster Jones. After being released from the penitentiary for his appeal, according to the Times, he “shot a negro, who was hurried away on the first passing steamer by his friends, and died.” Indeed, the Arkansas Democrat observed that one of Hearn’s “favorite pastimes was to shoot at negroes to see them run.”

On Sunday, March 31, Hearn allegedly murdered Clyde King, a white man. King was the brother of William and Robert King, who operated “an extensive mill and lumber plant near Luxora.” Reportedly, the murder occurred “in one of the colored dives in Luxora.” There with his brother Jim, Hearn sat down at the piano and began “pecking on the keys with the muzzle” of his gun. He refused to stop when an African-American woman asked him to, leading King to upbraid him for his behavior. At this, Hearn “turned on his seat and shot King, the ball striking the breast centrally, ranging through the left shoulder,” killing him almost instantly. Hearn was later arrested at the home of his brother.

According to the Times, the lynch mob was motivated not just by a desire for vengeance as related to the murder of King, but also by a determination to “thwart, in anticipation, the further miscarriage of law and justice.” The lynching was described as “a very quiet affair” and the mob “thoroughly organized” and consisting of about fifteen people, all likely Luxora residents, “as the members entered Osceola on horseback and not over half a dozen citizens of the place were aware that a lynching had taken place until morning.” The mob posted sentries and disarmed a deputy sheriff and night policeman, taking from the former the keys to the jail where Hearn was being kept. Hearn, confronted by members of the mob, “sank to his knees and began to pray” and insisted that the shooting had been accidental. The mob hanged him, between 1:00 and 2:00 a.m., from a nearby tree that had reportedly been used for previous lynchings (perhaps the murders of Henry Phillips and Willis Sees), and there the body was left until about 9:00 a.m., when it was cut down and returned to the family.

The Democrat’s coverage of the affair resulted in a letter from one H. C. Dunavant, who insisted that “lynchings will never cease under the present judicial system in this state. The people have absolutely no confidence in our courts.” Dunavant, who described himself as a former Confederate soldier, in particular lamented the practice of “putting a man on the supreme bench regardless of age and infirmities, simply because he had been a Confederate soldier.”

For additional information:

“May Hearn.” Osceola Times, April 6, 1901, p. 4.

“Mob Again Takes the Law in Its Hands.” Osceola Times, April 13, 1901, p. 4.

“Regarding Lynching.” Arkansas Democrat, April 18, 1901, p. 4.

“Work of a Mob.” Arkansas Democrat, April 8, 1901, p. 5.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.