calsfoundation@cals.org

Little Rock Executions of 1885

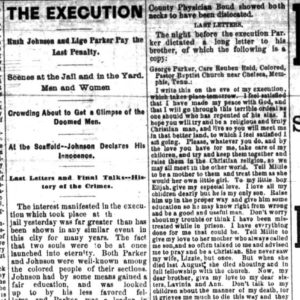

A pair of African American men, Rush Johnson and Lige Parker, were hanged together in Little Rock (Pulaski County) on February 12, 1885, after being convicted of first-degree murder.

Rush Johnson, described as a “young, muscular black negro,” was employed on the Pulaski County plantation of former governor Henry Massie Rector in the spring of 1884. On May 18, a steamboat arrived at the Rector place on the Arkansas River, and Carrie Johnson, “a heavy-set, copper-colored, depraved woman,” bought whiskey from it and got drunk. She went to the plantation store and got into an argument with superintendent John Wall, who kicked her out, with Johnson accusing him of striking her. Rush Johnson, described as Carrie Johnson’s “paramour,” was heard to say that he would shoot Wall if he struck her again.

Later, just after dark, someone fired a shot through the store window, “striking Wall in the groin just as he was in the act of stooping down to draw molasses from a barrel” and mortally wounding him. Johnson was arrested, though he maintained his innocence. At trial on October 3, 1884, a witness testified that he saw Johnson’s face in the pistol’s muzzle flash as the fatal shot was fired. A Pulaski County jury deliberated about one and a half hours before returning a verdict of guilty of first-degree murder. Johnson was sentenced to hang on November 26, 1884, the same day as murderer Frank Casey.

The Arkansas Supreme Court granted Johnson’s request for an appeal on November 18, 1884, delaying the execution, but the court confirmed the conviction on December 20. Johnson told the trial judge a few days later that he knew someone else had murdered Wall but later refused to confirm the man’s name to an Arkansas Democrat reporter because he could not be certain he was right. Governor James H. Berry pronounced that Johnson would hang on February 12, 1885.

Another man received the same execution date. Lige Parker, a Mississippi native who had been in Arkansas about seven years, was one of several men working on the Tate plantation in Pulaski County on December 12, 1884, when L. C. Fox refused to pay them for picking cotton “until it was well done.” Fox was shot to death as he worked in his office that night. (The Tate plantation would, two years later, be the site of a strike led by the Knights of Labor.)

Parker was arrested after several items belonging to Fox were found in his possession. He accused several of the other workers of involvement in the murder, but they were all cleared.

Parker was tried for Fox’s murder on December 24, 1884, and the jury deliberated “a couple of hours” before returning a first-degree murder verdict. Five days later, during his sentencing hearing, Parker said that Fox had promised him one dollar per day in pay but later paid him only ninety cents. He said that he later got his “needle gun” and went to Fox’s office; when he looked up, Parker says, he shot Fox in the mouth and, after waiting awhile, went in and “got the watch, pistol, knife and money that the officers found at his house when they arrested him.” He was condemned to hang on February 12, 1885.

On the day of their execution, an Arkansas Gazette reporter visited their cell and found Johnson reading the Bible to Parker, writing that “they both express a readiness to meet their fate and both are confident that they will journey together up into the Abrahams [sic] bosom.”

A crowd mostly comprising Black people began to gather around the Pulaski County jail on the morning of February 12, and by 11:00 a.m. “a dense throng surged back and forth in the street. The roofs of neighboring buildings swarmed with people.” Around 1,500 people were allowed into the jail yard where the executions would take place.

Johnson, who maintained his innocence to the end, and Parker were allowed to have friends visit them in the jail before they were taken to the gallows, mounting the scaffold at 11:55 a.m. Johnson thanked the sheriff for his kind treatment during nine months of incarceration and said, “I am going, but I am dealt with wrongfully when I am hung, though I bear no malice.” Parker said that “though it is hard to die as I must, I have prayed and I hope God has forgiven my sins.” The trap door opened around noon, and both men were declared dead twelve minutes later, their necks broken.

For additional information:

“A Confession.” Arkansas Democrat, December 24, 1884, p. 2.

“Appeal Granted.” Arkansas Democrat, November 18, 1884, p. 3.

“Arkansas State News.” Southern Standard, January 17, 1885, p. 1.

“Arkansas State News.” Southern Standard, October 18, 1884, p. 4.

“Doomed to Die.” Arkansas Gazette, December 30, 1884, p. 4.

“The Execution.” Arkansas Gazette, February 13, 1885, p. 4.

“The Fox Murder.” Arkansas Democrat, December 18, 1884, p. 2.

“Guilty.” Arkansas Democrat, October 4, 1884, p. 1.

“He Must Hang.” Arkansas Gazette, December 25, 1884, p. 8.

“Local Brevities.” Arkansas Democrat, December 20, 1884, p. 2.

“Miscellaneous Items.” Batesville Guard, December 3, 1884, p. 1.

“Murder of a Memphis Man.” Memphis, Tennessee, Public Ledger, January 2, 1885, p. 1.

“Parker Preaches.” Arkansas Gazette, December 19, 1884, p. 4.

“Two More.” Arkansas Gazette, February 12, 1885, p. 5.

Mark K. Christ

Central Arkansas Library System

Law

Law Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Johnson and Parker Execution Story

Johnson and Parker Execution Story

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.