calsfoundation@cals.org

Linnie Drown [Steamboat]

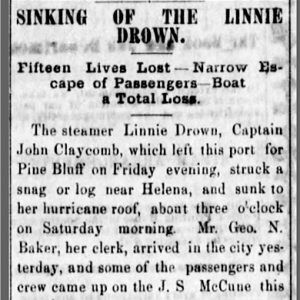

The steamboat Linnie Drown was running a circuit between Memphis, Tennessee, and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) when it struck an obstruction in the Mississippi River on September 7, 1866, near Helena (Phillips County). Between four and twenty-one people were reported to have died in the accident.

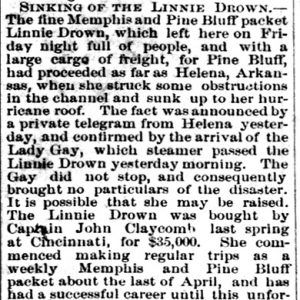

The Linnie Drown was a 229-ton sternwheel paddleboat built in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1864, running a route between that city and Marietta, Ohio, for about a year before being sold for $35,000. The new owners—Captain John Claycomb, clerk George N. Baker, and David Gibson—then ran the steamboat between Memphis and Pine Bluff.

The vessel was heading downriver at around 3:00 a.m. on September 7, 1866, carrying sixty passengers and 300 tons of freight, “mostly dry goods.” As it neared Island No. 60 on the Mississippi, it struck either a snag or the wreckage of the St. Nicholas, which had sunk after an 1859 boiler explosion and fire that killed sixty people, “tearing out her whole bottom.”

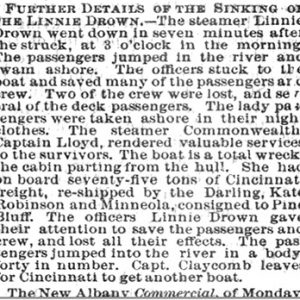

Claycomb aimed the boat toward shore, but the Linnie Drown swung back into the current before a line could be made fast. The Daily Memphis Avalanche reported that “nearly all the cabin passengers, as well as those on deck, jumped overboard,” with eleven passengers and ten crew members losing their lives as the Drown sank in seven minutes. A different account reported that “the lady passengers and the officers of the boat were all saved, and only those who were frightened and jumped overboard were lost.”

Another newspaper said that “the cabin passengers rushed from their staterooms onto the hurricane [deck] roof, having no time to save their baggage, many of them being in their night clothes, considering themselves lucky to save their lives” as the boat’s engineers manned their posts until the water was waist deep, after which they swam ashore. Claycomb himself, after ensuring his wife and child were safe, swam through the cabin areas to make sure the passengers had reached safety.

The steamboat Lady Gay came across the wreckage of the Linnie Drown, but it sailed by without offering any assistance. Another vessel, the Commonwealth, stopped, and the crew “did all in their power for the survivors.”

The Linnie Drown, its cabins separating from the hull, came to rest about 100 feet from Helena. Insured for $24,000, “it is thought she will prove a total loss.”

The Linnie Drown catastrophe provides another illustration of the dangers of steamboat travel in Arkansas waters in the nineteenth century, where encounters with snags also caused casualties on the Neosho in 1837, the Belle Zane in 1845, the John Adams in 1851, the Cambridge in 1862, the Mercury in 1867, the G. A. Thompson in 1869, and the Nick Wall in 1870.

For additional information:

“Further Details of the Sinking of the Linnie Drown.” Evansville [Indiana] Daily Journal, September 12, 1866, p. 7.

“Sinking of the Steamer Linnie Drown.” Memphis Daily Post, September 10, 1866, p. 5.

“Sinking of the Linnie Drown.” Daily Memphis Avalanche, September 11, 1866, p. 3.

“Sinking of the Linnie Drown.” Memphis Daily Argus, September 9, 1866, p. 3.

“Sinking of the Linnie Drown.” Memphis Public Ledger, September 10, 1866, p. 3.

Way, Frederick, Jr. Way’s Packet Directory. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1983.

Mark K. Christ

Central Arkansas Library System

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.