calsfoundation@cals.org

Lepanto (Poinsett County)

| Latitude and Longitude | 35°36’40″N 090°19’47″W |

| Elevation: | 223 feet |

| Area: | 1.56 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 1,732 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | February 25, 1909 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

|

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

154 |

986 |

1,195 |

1,198 |

1,683 |

1,585 |

1,846 |

1,964 |

2,033 |

2,133 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1,893 |

1,732 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A product of the timber industry and the railroads, the city of Lepanto grew through the twentieth century from a western-style logging community into an agricultural center for Poinsett County. Today, the city is most famous for its annual Terrapin Derby and for its appearance in the movie A Painted House.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

Lepanto is located within the sunken lands of northeast Arkansas. Prior to the construction of levees and drainage ditches, it was merely a high spot in the canebrake swamp, though the area was also heavily forested. The first known settler in the area was George Nichols, who moved to Arkansas from Dunklin County, Missouri, around 1858. More settlers came into the area in the 1870s, including John Potter, W. C. Marshall, and David Seely Buck. Buck requested a U.S. post office for the settlement, then called Potter’s Landing, so he would not have to travel several miles to Marked Tree (Poinsett County) to pick up his mail. When the request was granted in 1894, the postal service asked the settlers to select a different name for the post office. They selected the name Lepanto, for a famous port in Greece. No other community in the United States is named Lepanto.

Although a school was begun in Lepanto the same year that the post office was established, only nine students attended, and little more was added to the community until the beginning of the twentieth century.

Early Twentieth Century

During the first twenty years of the twentieth century, the timber industry flourished in northeast Arkansas, bringing many workers and their families into the area. In 1902, Steve Ralph and Henry S. Portis built a cotton gin in Lepanto so that harvested cotton would not have to be shipped downriver to Memphis, Tennessee. The next year, Charles Bryan Greenwood, who had recently moved into the area from Harrisburg (Poinsett County), commissioned four engineers to plat the city. The five main streets of the city were named for Greenwood and the engineers. William C. Dawson built the city’s first sawmill in 1905, and a new logging camp was built between Lepanto and Marked Tree.

The city grew rapidly. Improved drainage was completed by 1907, and the city was officially incorporated in 1909. A bank and a telephone company were established in 1910, a railroad depot was built in 1912, and the city’s first newspaper, the Lepanto Enterprise, began publishing in 1915. Although the Enterprise folded in 1918, it was replaced in 1922 by the Lepanto News Record, which remained in business until 1971. A Methodist church was organized in 1903, followed by a Baptist church in 1908. Two railroads served the city. The first, the Tyronza Central Railroad, was later acquired by the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway Company (Frisco). The second, the Blytheville, Leachville, and Arkansas Southern Railway, was eventually used by the St. Louis Southwestern Railroad (Cotton Belt). Houses and stores were also being built, and a new school building was erected in 1913. The Portis Mercantile Building was constructed in 1915, and a volunteer fire department was organized by 1919.

Many men from Lepanto served in the U.S. armed forces during World War I. In the following decade, even as the timber industry was already in decline, Lepanto continued to be viewed as a rough logging community. Local historians note that “taverns were located all over town, and moonshine and white lightning were as plentiful as soda pop. Most everyone owned and carried a firearm and, if sufficiently provoked, let it fire.” Notorious crimes included the armed confrontation of Chess Murphy and “Cowboy Jack” Globo on a train leaving Lepanto for Marked Tree in 1925, as well as the shooting of Elmer Barger by his wife, Nellie, who fired upon him after refusing to dance the Charleston at his bidding.

The decline of the timber industry and the collapse of cotton prices after World War I, along with damage from the Flood of 1927, all brought economic hardship to Lepanto even before the national experience of the Great Depression. Both banks in Lepanto failed, although the Little River Bank, originally based in Keiser (Mississippi County), then moved into the abandoned Bank of Lepanto building. Unemployment was high, and citizens welcomed the introduction of federal programs, including the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and canning kitchens. Construction projects in Lepanto included a brick city hall, a fire department building, an American Legion hall, and the paving of city streets. Elmer Murphy built a thirty-by-ninety-foot general store, considered large for the time, to serve the citizens of Lepanto.

The Lepanto Terrapin Derby began as a fundraiser for the American Legion in 1930. In its early years, competitors brought their own turtles to enter in the race, although more recently all the racing turtles have been donated by a local individual. The race and accompanying festival were produced by the Lepanto USA Museum from 1981 to 1999; since then, the Lepanto Fire Department has continued the city tradition.

Reportedly, the last lynching in Arkansas occurred on April 29, 1936, when Willie Kees, an African-American man who had been accused of rape, was taken from police custody in Lepanto and killed by a group of masked men.

World War II through the Faubus Era

On October 18, 1940, 733 men reported to the Lepanto school to register for the draft. Jimmy Hendrix of Lepanto was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroic service during the war. Several smaller school districts were consolidated into the Lepanto school district during the 1940s. A gymnasium and auditorium were added to the school in 1944, constructed by German prisoners of war who were being held in Marked Tree.

Following the war, the city continued to revive from its Depression-era troubles. A garden club was established in 1953, and an art club began meeting in 1964. After the bridge over the Little River collapsed in 1957, a new bridge was built, which was dedicated in 1963. The Federal Housing Authority (FHA) built forty low-rent units in Lepanto during the 1960s. Cotton became less important of a crop as soybeans and rice were added to area farms.

Bondsville (Mississippi County) schools were consolidated into the Lepanto school system in 1964. A community library was opened in 1967, and a new school gym was dedicated in 1968. Black students had been sent out of the community—elementary students to Spear Lake (Poinsett County) and high school students whose families could afford tuition payments to Marked Tree—until the Lepanto schools were desegregated in 1966.

Modern Era

Lepanto continues to flourish in the twenty-first century, with the Terrapin Derby the first Saturday of each October, a volunteer fire department with twenty-five members, seven churches, six restaurants, three antique shops, a medical clinic, and the school system. Enrollment as of 2010 is 400 high school students and 430 elementary school students. The Saturday night auction is considered one of the highlights of the city schedule. The Lepanto USA Museum opened in 1981.

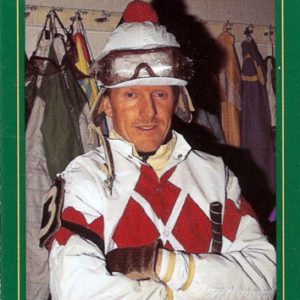

Famous citizens of Lepanto have included war hero Jimmy Hendrix, jockey Perry Wayne Ouzts, musician Buddy Jewell, and newspaper editor Esther Bindursky. The movie A Painted House, based on a book by Arkansas writer John Grisham, was filmed in Lepanto in 2002.

For additional information:

“Lepanto Commercial Historic District, Lepanto, Poinsett County.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. Online at http://www.arkansaspreservation.com/National-Register-Listings/PDF/PO0196.nr.pdf (accessed February 15, 2021).

Poinsett County, Arkansas, History and Families. Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 1998.

Steven Teske

Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture

“That’ll do son” were last words by Clarence “Red” Cooper, uttered as his oldest son, Cecil, attempted to comfort his papa after an assassin’s bullet had ripped into his chest. Cecil said, “Papa, I will go get Ellick and Mama.” “That’ll do son,” was Clarence’s response. His final words. By the time the family got to him, he was gone and the assassin could be heard crunching through the countryside of the January 1924 winter. The killing occurred about a mile and a half from Lepanto. The river was flooded and the bridge to Marked Tree was out. Three men crossed and two lived. Red’s murder was never solved. From what I understand about that period, life was not revered, especially for those involved in selling moonshine. As Cooper was not a sympathetic person to the local constabulary, not much effort was made to solve the crime. Earl Cooper, the middle son of Clarence, spent the remainder of his life anguishing over the tragedy. Moreover, his family and future grandson were robbed from the experience of knowing a period cowboy who could tell stories.