calsfoundation@cals.org

Lee Simms (Trial and Execution of)

A young African-American man named Lee Simms (sometimes identified as Sims) was executed in Little Rock (Pulaski County) on September 5, 1913; he was the first person to die in Arkansas’s new electric chair.

In June 1913, the Arkansas General Assembly passed a law specifying that future executions would be carried out at the state penitentiary in Little Rock using the electric chair. Prior to this, executions had been performed in the county where the crime occurred, and hanging was used. According to the Newark Journal, Arkansas’s chair was a “home-made product,” built at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) at a cost of $702.05. It was tested successfully in mid-August on a large steer and found to be effective.

According to the Arkansas Gazette, the crime of which Simms was accused took place near Brasfield in Prairie County, probably on July 26. According to accounts, Simms went to the home of an unidentified white man and found his daughter lying on a bed, whereupon he covered her face with a blanket and assaulted her. After Simms was arrested, the Prairie County sheriff, fearing mob violence, took Simms to the Pulaski County jail the following morning for safekeeping. He allegedly confessed on his way to Little Rock. By August 2, only a week after the assault, Simms had been returned to Prairie County, and his case had begun in a hastily organized court session in DeValls Bluff (Prairie County). On Monday, August 4, he was convicted and sentenced to death in the electric chair. According to the Log Cabin Democrat of Conway (Faulkner County), because of his confession there was no possibility of appeal.

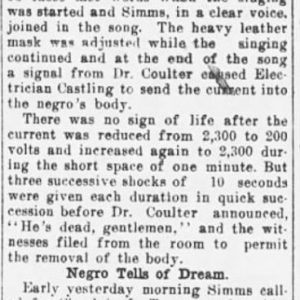

Simms was executed on September 5. According to the East Oregonian and several other papers, Simms “was undeniably proud of the ‘distinction’” of being the first to die in the chair, and “went to his death smiling.” Apparently, the new Arkansas statute specified that reports of executions were to contain only the bare facts, none of the lurid details of the execution itself. While most Arkansas newspapers abided by this rule, several apparently did not, and the Log Cabin Democrat reported these papers would be prosecuted.

The executioner that day was Luther Castling, who had worked at the penitentiary as an electrician. Interestingly enough, in November of the following year Castling resigned his position, either because he could not face the prospect of executing the ten men on death row at that time, or because he refused to execute Neal McLaughlin, the first white man on death row, who was next on the list.

Despite the extensive coverage of Simms’s execution, the February 1914 issue of The Crisis listed his death among lynchings across the country in 1913. It has since appeared on several lynching websites, as well as in at least one book, Ralph Ginzburg’s 100 Years of Lynchings.

For additional information:

“Arkansas Inaugurates Electric Chair.” East Oregonian, September 5, 1913, p. 2.

Ginzburg, Ralph. 100 Years of Lynchings. Baltimore, MD: Black Classics Press, 1988.

“Lee Simms Dies in Electric Chair.” Arkansas Gazette, September 6, 1913, p. 12.

“May Prosecute Papers.” Log Cabin Democrat (Conway, Arkansas), September 9, 1913, p. 3.

“Negro Confesses Attacking Woman.” Arkansas Gazette, August 3, 1913, p. 13.

“Negro Held for Assault.” Arkansas Gazette, July 28, 1913, p. l7.

“Prairie County Negro First to Die in Chair.” Log Cabin Democrat (Conway, Arkansas), August 5, 1913, p. 4.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Lee Simms

Lee Simms  Lee Simms Article

Lee Simms Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.