calsfoundation@cals.org

Lee Henslee (1903–1963)

Lee Henslee was the longest-serving superintendent of the Arkansas prison system. He was appointed head of the state penitentiary in 1949 by Governor Sid McMath and served in that position until 1963. Henslee received praise from Governor Orval Faubus, but he was superintendent in a time when abuse and corruption at the prisons were rampant.

Lee Henslee was born on September 4, 1903, on a family farm five miles east of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). He was one of three children born to Edward Anderson Henslee (1863–1949), a native of Mississippi, and Clara Belle Treadwell Henslee (1874–1963), a native of Arkansas. Lee Henslee grew up in Pine Bluff. He married Mississippi native Mary Alcorn (1902–1990) on August 22, 1924, in McAllen, Texas. The couple had four children. He attended the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) but never graduated.

Before working in law enforcement, Henslee worked on the family farm in Jefferson County, for a family railroad-building business, and in road construction in Harrison (Boone County). In the 1930s, he worked as a deputy sheriff in Pine Bluff before rising to manager of the Arkansas prison system. By 1940, Henslee was an assistant superintendent at Tucker prison farm in Jefferson County. In 1949, he was made superintendent of the state penitentiary. Beneath him in the prison hierarchy were wardens who ran Tucker and Cummins prison farms. At the time, the prison system consisted of three facilities: Tucker, Cummins, and the women’s reformatory, which was adjacent to Cummins. The prisons were run for profit, though they were not necessarily profitable every year. To make the farms less reliant on cotton, Henslee diversified crop production, which resulted in inmates cultivating soybeans, rice, and cucumbers as well as cotton.

By the time of the Faubus era, which began in 1955, Henslee’s tenure as superintendent epitomized the “old guard” system of prison management. A few years into his reign as superintendent, Henslee hired Jim Bruton as superintendent of Tucker. Bruton was the keeper of the infamous Tucker Telephone, a torture device, and later was convicted of civil rights violations, though he never served prison time. Under Henslee’s supervision, the vast majority of prison guards were “trusties,” who were inmates with almost complete power over fellow prisoners. Beatings, whippings, murder, rape, theft, and bribery were commonplace at Tucker and Cummins. Reformer Tom Murton chronicled such abuses in his bestselling book Accomplices to the Crime, though crimes committed at the prisons were documented long before then. Dale Woodcock’s 1958 self-published book Ruled by the Whip gave a chilling look at the prisons of the Henslee era. Despite the human rights abuses at the prisons, conservative elements strove to keep the penitentiary as it was.

Henslee oversaw the construction of a new building for women prisoners in 1951, but the concern for inmates—male or female—was shockingly absent. Rehabilitation programs were non-existent. Healthcare was poor, and the prisoners were fed on starvation rations. In 1952, however, Henslee told the Arkansas Gazette that the prison farms were superior to prisons elsewhere because they kept men at work and out in the open, all for very little cost. In 1953, the Gazette published an article on Henslee that described him as a man with the “patient understanding of Job.” The paper chronicled him sending sixty-seven men to the electric chair. Up to that time, Arkansas had executed 151 prisoners, three-quarters of them African American. Henslee called execution “the finest form of moral discipline in my institution.”

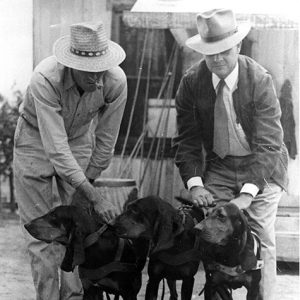

Henslee was not often photographed by the media, but he had a good relationship with Joe Wirges, the police reporter at the Gazette for forty-nine years. Wirges sometimes traveled to Cummins for his vacations, where he would sleep in an empty cell and visit and hunt with Henslee. Prisoners thought less of “Cap’n Lee,” as Henslee was known. Lamar House, an inmate who wrote extensively on the prison system once he was free, called Henslee a “tormentor” who abused his “slaves.” House concluded that as long as Faubus and Henslee were in charge, “a convicts [sic] life was worth nothing.”

Henslee resigned his positon on July 1, 1963, citing ill health. He remained in Pine Bluff. On October 16, he killed himself with a twenty-gauge shotgun. Colonel Herman Lindsey, who headed the state police, called Henslee “one of the very best personal friends I ever had,” adding, “He meant so much to law enforcement.” Faubus also praised Henslee, claiming he “served his state long and well” and was “one of the greatest penologists in America.” He is buried in Graceland Cemetery in Pine Bluff.

Despite Faubus’s praise, Henslee’s methods epitomized an era of prison management that has since been deemed primitive, corrupt, openly racist, and inhumane. Three years after Henslee’s death, the so-called old guard began losing its grip on the penitentiary. In 1966, the state police began an investigation of Tucker, the horrors of which created a national and, later, international scandal.

Under Governor Winthrop Rockefeller’s tenure and that of his successors, Arkansas improved daily prison conditions, professionalized administration, and hired trained penologists and outsiders to overhaul the system. In 1970, nevertheless, federal Judge J. Smith Henley called the prisons a “dark and evil world,” ruling the entire prison system in Arkansas unconstitutional.

For additional information:

“Former Head of State Prison Is Found Dead.” Arkansas Gazette, October 17, 1963, p. 2A.

House, Lamar. “Memories of a Slave Prison.” Undated manuscript. Arkansas Small Manuscript Collection, 1823–1986. Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Lee Henslee.” Arkansas Gazette, October 18, 1963, p. 6A.

“Former State Prison Chief Is Suicide.” Hope Star, October 17, 1963, p. 1.

Overholt, Charles. “Cap’n Lee’s Pride Is Quiet.” Arkansas Gazette, January 11, 1953.

Wirges, Joe. “Field Work for Convicts Relieves Prison Tension.” Arkansas Gazette, May 4, 1952, p. 2F.

———. “Transfer of Women Poses Old Problem to Prison Farm, Prompts New Solution.” Arkansas Gazette, 1951, pp. 1A–2A.

Woodcock, Dale. Ruled by the Whip: The Hell behind Bars in America’s Devils’ Island, the Arkansas Penitentiary. New York: Exposition Press, 1958.

Colin Woodward

Lee Family Digital Archive, Stratford Hall

Lee Henslee

Lee Henslee

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.