calsfoundation@cals.org

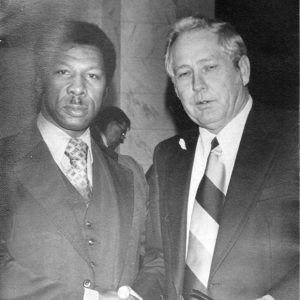

Knox Nelson (1926–1996)

Knox Nelson was a member of the Arkansas General Assembly for thirty-four years in the second half of the twentieth century, achieving power in legislative halls that was rarely rivaled. Nelson was elected to the state House of Representatives from Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) in 1956 and served two terms, but he attained a position of immense power in the thirty-year career in the state Senate that followed. Governors and groups interested in legislation often had to win Nelson’s favor to get bills passed or defeated in the Senate.

Knox Nelson was born on April 3, 1926, in the Goatshed community near Moscow (Jefferson County), a farming community a few miles south of Pine Bluff. His father, Knox Augustus Nelson, and his mother, Audie Burnett Truitt Nelson, were farmers. The family did not have electricity or running water, and he would later say that, as a child, he watched through cracks in the floor as chickens scratched under the house.

Drafted into the U.S. Army, he was sent to the South Pacific in the late stages of World War II and left the army as a staff sergeant. He held various jobs until he bought a gas station in Pine Bluff. Later, when his political career took off, he moved into a lucrative bulk-oil business as regional distributor for Socony Mobil Oil Corp. It became the Knox Nelson Oil Company. He joined the Young Democrats and the “GI Revolt,” which elected Sid McMath governor in 1948. He married Nancy Cearley of Pine Bluff on June 18, 1949, and they had one daughter.

After being elected to the House of Representatives in 1956, he quickly learned the ropes of legislative politics. When Witt Stephens, the powerful president of Arkansas Louisiana Gas Co. (Arkla), asked the legislature to pass a bill overriding an Arkansas Supreme Court decision that limited the amount of money the gas company could charge customers for gas that the company produced from its own wells, Nelson signed on. The bill was introduced, passed, and signed into law in three days in February 1957, only weeks into Nelson’s first term in the legislature. When Nelson went home that weekend, an employee at his service station said that an Arkla representative had been to the station to tell Nelson that all the company’s trucks in the area would buy all their gasoline at the station. Stephens gave Nelson an interest-free loan to buy a farm on the edge of Lincoln County near the Nelson family home, where Nelson would raise cattle and grow cotton and soybeans.

In 1960, he ran for one of two seats in the state Senate from Jefferson County and was elected easily; he would not get another opponent until 1990, when Jay Bradford defeated him. In his first term in the Senate, Nelson was appointed chairman of the Rules Committee, a position that had no role except settling occasional parliamentary disputes. That would change six years later with the election of the first Republicans to statewide office since Reconstruction. The lieutenant governor, who presided, had been the eminent power in the Senate because he controlled the calendar of business and exercised full parliamentary authority.

Thirty-four of the thirty-five senators were Democrats, and they changed the Senate rules in 1967 after Republican Maurice L. “Footsie” Britt was elected lieutenant governor, along with a Republican governor, Winthrop Rockefeller. The chairman of the Rules Committee became the parliamentary arbiter and took control of the daily calendar of business. Nelson could determine which committee a legislator’s bill was assigned to and when the Senate would vote on it. He worked at the job assiduously, patrolling the floor and directing the proceedings nearly every minute of a session, often murmuring instructions to senators. He cultivated a friendship with every new senator, and they came to him for advice and help in getting their bills to the floor and in passing them. He became a permanent member of the Arkansas Legislative Council and the Joint Budget Committee, which acted on all spending bills, and also chairman of the Public Health, Welfare and Labor Committee, through which much crucial legislation passed. His power was exercised jointly with Max Howell, who became the longest-serving member of the legislature in Arkansas history.

The Associated General Contractors of Arkansas, a trade organization, hired Nelson as its executive director. His job was to manage its considerable political and governmental affairs. Nelson rarely participated in floor debates or sponsored important bills. His name is associated with no major legislation in thirty-four years in the legislature, but his fingerprints were on numerous ones, including taxes for highway construction. The Associated General Contractors of Arkansas had a keen interest in highway and general state construction. Nelson did not sponsor legislation favorable to the industry, but he found sponsors for the bills and quietly shepherded them into law. He did that for other groups as well.

Nelson also took a keen protective interest in the state penitentiary, the largest unit of which was near his farm. He resisted the prison reform efforts of Governor Rockefeller from 1967 to 1971, and governors from Dale Bumpers to Bill Clinton found that Nelson’s influence over prison operations often exceeded theirs.

In an interview in 1977, he explained the appearance of overriding influence this way: “Any success I have is because I want to help my colleagues do a good job. People reciprocate when you help them.”

Nelson exercised his greatest reach in the late 1980s, particularly in the legislative sessions in 1987, 1988, and 1989, in which he helped stymie Governor Bill Clinton’s initiatives on tax, budget, and prison matters. A court-ordered reapportionment changed the boundaries of Senate districts around Jefferson County and placed him and Sen. Jay Bradford, with whom he had served in the Senate since 1983, in the same district. In 1990, they ran for the same seat. Betsey Wright, who had been Clinton’s campaign manager and chief of staff since 1982, worked almost full time in the spring of 1990 for Bradford, a close ally of Clinton. Bradford won handily with nearly sixty-two percent of the vote.

Nelson died on June 4, 1996. He is buried in Pine Bluff Cemetery.

For additional information:

“Bradford Beats Knox Nelson in District 28.” Arkansas Gazette, May 30, 1990, pp. 1A, 11A.

Griffee, Carole. “Pragmatism, Diplomacy Help Nelson Gain Power.” Arkansas Gazette, February 20, 1977, p. 5A.

Harold, Shareese. “Knox Nelson, 70, Dies.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 5, 1996, pp. 1A, 19A.

Talbot, George, III. “Longtime Senator K. Nelson Is Dead.” Pine Bluff Commercial, June 5, 1996, pp. 1A, 2A.

Trimble, Mike. “Knox without Tears.” Arkansas Times, January 1991, pp. 39, 51.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.