calsfoundation@cals.org

Keller Bramwell Breland (1915–1965)

Keller Bramwell Breland was perhaps best known in Arkansas as the co-owner and operator of the IQ Zoo, a tourist attraction in Hot Springs (Garland County) that featured trained animals performing a variety of amazing acts. In addition, Breland played a major role in developing scientifically-validated and humane animal training methods and in promoting the widespread use of these methods.

Keller Breland was born on March 26, 1915, in Poplarville, Mississippi, to Aden Breland, a Methodist minister, and Eugenia Breland, an elementary school teacher. The youngest of eleven children, Keller was an inquisitive, resourceful child. An entrepreneur from an early age, he sold magazines door to door with his older brother, Homer, and picked cotton during the summers. Breland graduated from Copiah-Lincoln High School and Junior College in Wesson, Mississippi, in 1933. In 1937, he earned a BS in psychology from Millsaps College in Jackson, Mississippi, and followed that with an MA in psychology at Louisiana State University in 1939. While a doctoral student in industrial psychology at the University of Minnesota, he met Marian Ruth Kruse. Their first meeting involved animals, specifically a rat. The story is that Marian was running down a hallway after being bitten by a laboratory rat and literally ran into Keller. They were married on August 1, 1941, and had three children, Bradley (1946), Frances (1948), and Elizabeth (1952).

In the 1940s, operant conditioning, the provision of positive or negative consequences following a behavior to increase or decrease the occurrence of the behavior, was in its infancy. During graduate school at the University of Minnesota, both Keller and Marian were students of B. F. Skinner, the famous behavioral psychologist. The Brelands assisted Skinner on Project Pigeon, the World War II effort that trained pigeons to guide bombs. During this project, Breland witnessed the power of operant methods to train animals efficiently to perform complex behaviors. (The pigeon-guided missile system worked but was never used.) He became convinced that he and his wife could make their living using operant psychology to train animals. Thus, against the advice of Skinner and their peers, the Brelands left the University of Minnesota (prior to completing their degrees) and, on a small farm in Mound, Minnesota, started the first commercial application of operant conditioning, Animal Behavior Enterprises (ABE).

The Brelands’ first contracts were with General Mills to train animals for farm feed promotions. As ABE became more successful, they outgrew their farm and began looking for larger quarters. As a Southerner, Keller hated cold weather, so in 1950, he and Marian moved ABE to a large farm in Lonsdale (Garland County), outside Hot Springs. This central Arkansas location also offered access to railroad connections for shipping animals across the country, as well as connections to the thriving tourist business in Hot Springs.

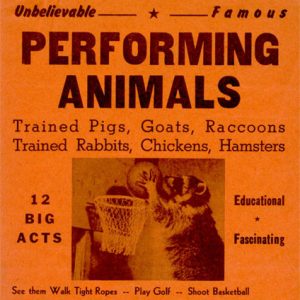

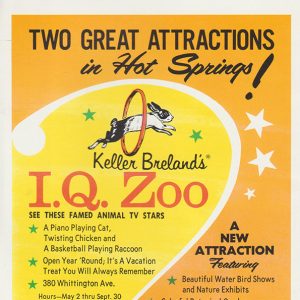

In 1955, Keller and Marian opened the IQ Zoo at 380 Whittington Avenue in Hot Springs (it was later moved to 422 Central Avenue). The IQ Zoo featured a showcase of animals trained by the Brelands and served as a training facility. Popular acts included chickens that walked tightropes, dispensed souvenirs and fortune cards, danced to music from jukeboxes, played baseball and ran the bases; rabbits that kissed their (plastic) girlfriends, rode fire trucks and sounded sirens, and rolled wheels of fortune; ducks that played pianos and drums; and raccoons that played basketball. The History Channel rated the IQ Zoo one of the most popular roadside tourist attractions during the twentieth century.

The popularity of the IQ Zoo brought Keller and Arkansas to the attention of the commercial animal training industry. In the 1950s, he and Marian developed the first operant-based marine mammal and bird shows for Marineland of the Pacific, Marine Studios, and Parrot Jungle. Keller and his animals also appeared on numerous television programs, such as Ed Sullivan, Dave Garroway, Jack Paar, Steve Allen, Zoo Parade, You Asked for It, and Industry on Parade. Animal trainers from across the country came to Hot Springs to learn the Brelands’ techniques. Today, the animal training programs at most major theme parks and oceanariums, such as Sea World and Busch Gardens, can be traced back to Keller and Marian Breland.

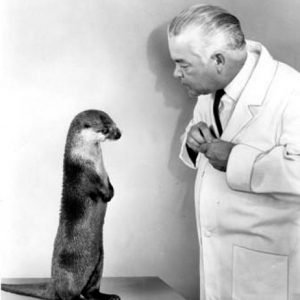

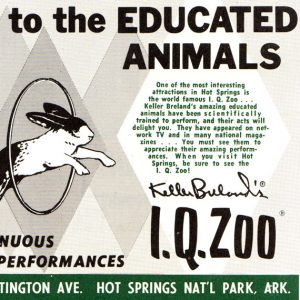

The Brelands were equal collaborators in ABE. They were both talented trainers. Keller Breland, however, was the public face of ABE until his death in 1965. Advertisements referred to “Keller Breland’s Educated Animals” and “Keller Breland’s IQ Zoo.” He often made public appearances with the animals at county and state fairs, feed stores, and on television. Pictures of Breland training animals frequently appeared in newspapers and magazines.

In the preface to their 1966 textbook, Animal Behavior, his wife Marian described him as the “dreamer” and herself as the “engineer.” He was the idea man; she made it all work. Breland strongly believed in the power of science and technology to improve life. He was ahead of his time in understanding that operant training methods could revolutionize animal training to be more effective, efficient, and humane. Mid-twentieth-century animal training methods were notoriously inconsistent and relied on physical punishment. Breland emphasized that his animals were neither punished nor mistreated.

Breland also recognized the potential uses of trained animals for commercial purposes. His animal acts were used to advertise products ranging from livestock feed to banking institutions. ABE animals were described in periodicals including Time, Reader’s Digest, Wall Street Journal, and Life. He developed shows and training methods for oceanariums and theme parks throughout the U.S. The training methods he pioneered in the 1940s and 1950s are still used today. The Brelands’ scholarly writings on behavioral psychology also continue to influence the study of animal behavior.

Breland died of a heart attack on June 17, 1965, in Hot Springs. He is buried in Wesson, Mississippi.

For additional information:

Breland, K., and M. Breland. Animal Behavior. New York: Macmillan, 1966.

———. “The Misbehavior of Organisms.” American Psychologist 16 (1961): 681–684.

———. “A New Field of Applied Animal Psychology.” American Psychologist 6 (1951): 202–204.

Gillaspy, J. A., and E. Bihm. “Obituary: M. Breland Bailey (1920–2001).” American Psychologist 57 (April 2002): 292–293.

J. Arthur Gillaspy Jr. and Elson M. Bihm

University of Central Arkansas

Film collected in Industry on Parade TV show 433: https://sirismm.si.edu/EADpdfs/NMAH.AC.0507.pdf

Reel AC0507-OF0433 Episode 433, 1959 January 31 1 Motion picture film

Notes: Animals and Industry Household pets, zoos, and aquariums fill valuable role. Conservation programs protect wildlife and provide animals for hunters. Hunting a major industry. Billions are invested in cattle and poultry that provide food and clothing. Laboratory animals used in researching drugs and medical techniques. Study of animal psychology has aided in evaluating mental processes of humans. Filmed at: Ducks Unlimited, Inc., New York, NY; Ocean Aquarium, Hermosa Beach, CA; Charles Pfizer & Co., Inc., Brooklyn, NY; and Animal Behavior Enterprises, Hot Springs, AR.

He was my fourth cousin.