calsfoundation@cals.org

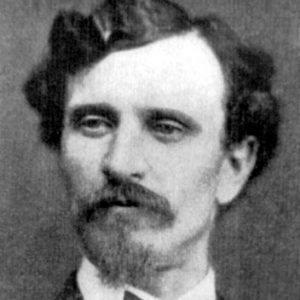

John Middleton Clayton (1840–1889)

John Middleton Clayton was a Union officer, Reconstruction official, county sheriff, and Republican Party activist. His life in Arkansas illustrates the contentious politics in the state and the South of this time, and his politically inspired murder in 1889 may have made him more famous in death than in life.

John Clayton and his twin brother, William, were born on October 13, 1840, on a farm near Chester, Pennsylvania, the son of Ann Glover and John Clayton, an orchard-keeper and carpenter. The couple had ten children, six of whom died in infancy.

Clayton married a woman named Sarah Ann, and the couple had six children.

During the Civil War, Clayton served in the Army of the Potomac and was engaged in several campaigns in the eastern United States. In 1867, he moved to Arkansas with his family and managed the plantation owned by older brother, Powell Clayton.

In 1871, Clayton was elected as representative for Jefferson County. In 1873, he served in the Arkansas Senate, representing Jefferson, Bradley, Grant, and Lincoln counties and served as speaker of the Senate, pro tem, for part of the year. He served on the first board of trustees of Arkansas Industrial University, now the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County), when it was chartered in 1871. Two years later, he helped Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) secure the Branch Normal College, now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff (UAPB). Clayton became involved in the Brooks-Baxter War in 1874, in which Joseph Brooks and Elisha Baxter both claimed the governor’s office. Clayton raised troops in Jefferson County and marched them to Little Rock (Pulaski County) to fight Baxter’s supporters. Clayton remained one of Brooks’s staunchest supporters to the end of the conflict, when President Ulysses S. Grant restored Baxter to the governor’s office.

Clayton remained involved in politics in the years after Reconstruction. With the support of black Republican voters, he became sheriff of Jefferson County in 1876 and was reelected for five successive, two-year terms. In 1888, he ran as a Republican candidate for the U.S. Congress against incumbent Democrat Clifton R. Breckinridge, who represented Arkansas’s second district. Clayton lost the election by a narrow margin of 846 out of over 34,000 votes cast. This election was known as one of the most fraudulent in Arkansas history. In one case in Conway County, four white masked men stormed into a predominately black voting precinct and stole, at gunpoint, the ballot box that contained a large majority of Clayton votes. Losing under such circumstances, Clayton contested the election. He went to Plumerville (Conway County), to investigate the stolen election. On the evening of January 29, 1889, someone shot through the window of the boardinghouse where he was staying, killing him instantly; this was the climax of an ongoing local conflict over political power.

The press in Arkansas and the nation condemned Clayton’s murder as a vile political crime. Despite a $5,000 reward, an investigation by Pinkerton detectives, and a study by the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Elections, no murderer was ever found. In 1890, the House voted that Clayton had indeed won the election in 1888 and declared the congressional seat vacant on account of Clayton’s death. After serving almost the entire term, Breckinridge lost his seat in Congress.

Clayton is buried in Bellwood Cemetery in Pine Bluff.

For additional information:

Barnes, Kenneth C. Who Killed John Clayton? Political Violence and the Emergence of the New South, 1861–1893. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1998.

Hempstead, Fay. A Pictorial History of Arkansas from Earliest Times to the Year 1890. St. Louis: N. D. Thompson, 1890.

Kenneth C. Barnes

University of Central Arkansas

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

I’ve lived in Arkansas my whole life and found out about this murder from a podcast. So then I had to learn more about it. It’s an interesting part of history that happened literally about an hour from where I grew up.