calsfoundation@cals.org

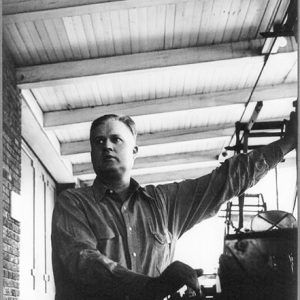

John Daniel Rust (1892–1954)

John Daniel Rust invented the first practical spindle cotton picker in the late 1930s. The Rust cotton picker threatened to wipe out the old plantation system and throw millions of people out of work, creating a social revolution. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin had created the “Cotton South,” but the Rust picker threatened to destroy it. In 1949, Rust moved to Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), where the Ben Pearson Company produced cotton pickers using the Rust patents.

John D. Rust was born on September 6, 1892, near Necessity, Texas, to Benjamin Daniel Rust, a farmer and schoolteacher, and Susan Minerva Burnett, a homemaker. As a youngster, Rust did farm work and displayed an aptitude for mechanical tinkering. His parents died when he was sixteen, and he drifted around Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. In 1924, Rust married Faye Pinkston and had two children. After they divorced, he married Thelma Ford of Leesville, Louisiana, in 1933.

Rust was intrigued with the challenge of building a mechanical cotton picker. Other inventors had used a spindle with barbs, which twisted the fibers onto the spindle and pulled the cotton lock from the boll, but the spindle became clogged with cotton. Rust concerned himself with how to strip the cotton from the barbs, the answer to which, he decided, was to use a smooth, moist spindle. Rust later said:

“The thought came to me one night after I had gone to bed. I remembered how cotton used to stick to my fingers when I was a boy picking in the early morning dew. I jumped out of bed, found some absorbent cotton and a nail for testing. I licked the nail and twirled it in the cotton and found that it would work.”

He went back to Texas to live with a sister in Weatherford. He assembled the first working model in her garage and tested it on ten artificial stalks set up on a board. The machine picked ninety-seven out of one hundred locks of cotton.

He continued testing with funds invested by family and friends. In 1928, his brother Mack, who held a degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas, joined him. Rust received his first patent in 1933. Eventually, he and his brother owned forty-seven patents.

During the Great Depression, the Rust brothers began a migration in search of financial support. In 1930, they moved to Louisiana’s Newllano cooperative community, which invested in their project. After two years, John and Mack moved on to New Orleans, where they chartered the Southern Harvester Company. Next they went to Lake Providence, Louisiana, where local planters financed their experiments.

In 1935, still in pursuit of financial backers, the Rust brothers relocated to Memphis, Tennessee, the center of the Cotton South, and they founded the Rust Cotton Picker Company, successor to the Southern Harvester Company. On August 31, 1936, the Rust picker was demonstrated at the Delta Experiment Station in Stoneville, Mississippi. Though the demonstration attracted national press coverage, it produced mixed results. The machine knocked cotton to the ground and accumulated bits of leaves and stems in the staple it picked, lowering the grade and the cotton’s price. But it did pick cotton, and the Rust Cotton Picker Company pledged to have 500 machines ready for the picking season in 1937.

The Rust machine sent a shockwave through the country. The reality of a machine that would actually pick cotton loomed over the South, potentially eliminating jobs and raising the specter of social convulsions in the midst of the Depression. The sharecropper or crop lien system, which had been in place since the end of slavery, faced collapse; thus the prospect loomed of millions of African American sharecroppers migrating to northern cities in search of employment that did not exist.

The Rust Cotton Picker Company, however, lacked financing for commercial production. The Rust brothers could build a few prototypes, but the production of thousands of machines required the resources of a large company. In addition, Rust was not convinced that his machine possessed the durability required in a commercial product. The brothers’ partnership dissolved, and Mack Rust moved to Arizona.

As the Rust Company slipped into bankruptcy, International Harvester Corporation of Chicago, Illinois, announced in 1942 that it had a production-ready model of a mechanical cotton picker. International Harvester (IH) had spent $5.25 million over two decades to develop a spindle-type picker. Unlike Rust’s, their picker used a barbed spindle, which improved its affinity for cotton fibers. However, the scarcity of steel during World War II delayed production. In 1947, International Harvester opened a new manufacturing plant in Memphis and became the first company to produce commercially a mechanical cotton picker. After World War II, the use of mechanical pickers slowly increased across the Cotton South. The Great Migration and the postwar period shifted millions of people from farms to cities and averted social disaster.

Though bankruptcy left Rust nothing but his drafting board, he set out in 1943 to redesign his spindle device in order to make it more durable. At last, his efforts paid off in two contracts. After the war, the Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, began the manufacture of pickers in Gadsden, Alabama, using the Rust patents. In 1949, Rust entered into another agreement with the Ben Pearson Company of Pine Bluff, an Arkansas company known for archery equipment. Rust moved to Pine Bluff to act as engineering consultant. Pearson went on to market Rust pickers internationally.

The Rust cotton picker achieved commercial success, and Rust, after years of hardship, became a wealthy man. He repaid his sponsors, established scholarships at colleges in Arkansas and Mississippi, and toyed with a universal language that he called “Plaantauk.” He died on January 20, 1954, just as the use of mechanical cotton pickers moved the South into a revolutionary new era of agribusiness. He is buried in Graceland Cemetery at Pine Bluff.

For additional information:

Carlson, Oliver. “The Revolution in Cotton.” American Mercury 34 (September 1935): 129–136.

Holley,Donald. The Second Great Emancipation: The Mechanical Cotton Picker, Black Migration, and How They Changed the Modern South. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Honeycutt, Tom. “The Second Great Emancipator: Eccentric Inventor John Rust Changed the Face of Modern Agriculture.” Arkansas Times 11 (February 1985): 76–78, 81–82.

“Mr. Little Ol’ Rust.” Fortune 46 (December 1952): 150–152, 198–205.

Rust, John. “The Origin and Development of the Cotton Picker.” West Tennessee Historical Society Papers 7 (1953): 38–56.

Straus, Robert Kenneth. “Enter the Cotton Picker: The Story of the Rust Brothers’ Invention.” Harper’s 173 (September 1936): 386–395.

Street, James H. The New Revolution in the Cotton Economy: Mechanization and Its Consequences. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1957.

Donald Holley

University of Arkansas at Monticello

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.