calsfoundation@cals.org

John Andrews Murrell (1806–1844)

Among legendary characters associated with nineteenth-century Arkansas, John Andrews Murrell occupies a prominent place. Counterfeiting and thieving along the Mississippi River, Murrell was only a petty outlaw in a time and place with little law enforcement. However, he became a greater figure in legend following his death.

John A. Murrell was born in Lunenburg County, Virginia, in 1806. His father, Jeffrey Gilliam Murrell, was a respected farmer who, with his wife, Zilpha Murrell, raised eight children. Shortly after John was born, the Murrells and other relations moved to Williamson County, Tennessee. However, Murrell’s father fell on hard times, and his sons, who were wild and errant, began to have trouble with the law. At the age of sixteen, Murrell, along with brothers William Murell and Jeffrey Gilliam Murell Jr., were charged with “riot” (disturbing the peace). In February 1823, Murrell was charged with horse theft. He languished in jail for several months before being tried and sentenced (after the fashion of that day) to thirty lashes, the pillory, branding, and one year in prison.

The elder Murrell died in 1824, leaving Zilpha to care for her wayward brood. She moved farther west through Tennessee, first to Wayne County, and, finally, to Denmark in Madison County. Murrell, who was released from jail in 1827, married Elizabeth Mangham, who bore him two children. Continuing to have brushes with the law, Murrell became a well-known troublemaker in Tipton, a village north of Memphis, Tennessee, as well as in the swamplands of eastern Arkansas—referred to locally as “the morass”—where outlaws headquartered at Shawnee Village, near present-day Joiner (Mississippi County). This vicious element preyed upon unsuspecting river traffic, struck counterfeit money, and aided and abetted horse and slave thieves. Murrell and his brother William were implicated in one such counterfeiting enterprise, while his brother Jeffrey was running stolen horses into Arkansas.

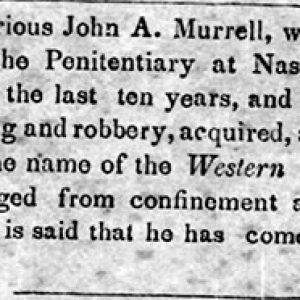

When John Murrell was suspected of stealing a slave in Madison County, Tennessee, in 1833, Virgil A. Stewart, a local resident, was employed to retrieve the slave. Stewart found Murrell and succeeded in ingratiating himself with the outlaw. Stewart accompanied him into Arkansas, where (according to Stewart), Murrell claimed to lead a large-scale criminal enterprise known as “the Mystic Clan.” Upon returning to Tennessee in February 1834, Stewart arranged for the arrest of Murrell. The following July, he testified at the trial of Murrell, who was convicted and sentenced to ten years of hard labor.

Murrell became a model prisoner, read the Bible, and learned the blacksmithing trade. When he contracted tuberculosis, he was granted early release in April 1844. He died in Pikeville, Tennessee, on November 1, 1844.

After his conviction, Murrell, who was just one of many minor criminals lurking along the Arkansas–Tennessee frontier, should have soon been forgotten. However, Virgil A. Stewart succeeded in elevating this petty thief to the ranks of one of America’s legendary criminals. In 1835, Stewart published A History of the Detection, Conviction, Life and Designs of John A. Murel [sic], The Great Western Land Pirate, in which he presented a highly exaggerated (and often fanciful) account of his conversations with Murrell on their trip to Arkansas. According to Stewart (whom some suspected of actually being an associate of the outlaw), Murrell was talkative and full of braggadocio, not only admitting to many heinous crimes but alleging that his organization planned to incite a slave uprising across the South on Christmas Day 1835. As a consequence of widespread newspaper coverage surrounding Stewart’s inflammatory pamphlet, Murrell’s reputation soon reached sensational proportions. The fact that the appearance of this book coincided with the agitation of the newly formed American Anti-Slavery Society prompted a wave of hysteria among slaveholders. Murrell’s lawlessness was “so extensive in its operations and so scientific in its plans,” wrote the imaginative Stewart, that it reached from Texas to the East Coast. The author even provided a list of names of alleged members for each state, including twenty-four Arkansas families.

The association of Murrell’s name with Arkansas continued to grow after his death. His brother Jeffrey was killed in a saloon brawl in Columbia (Chicot County) by a man named Franklin Stewart, reportedly a relative of Virgil A. Stewart. In another ironic twist, Stewart’s brother, Tapley, was arrested as part of a counterfeiting ring in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1842. John A. Murrell’s name was also associated with streams, springs, trails, and hills in eastern Arkansas. While marking a trail for his gang members, Murrell reportedly notched an oak tree at a ford on the St. Francis River—the present-day site of Marked Tree (Poinsett County). Rumors of buried loot from Murrell’s robberies abounded. Indeed, author Mark Twain, who was a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi River some years after Murrell’s death, concluded from hearing these tales that Murrell ranked with the most infamous of America’s frontier outlaws: “[Jesse] James was a retail rascal; Murel [sic] wholesale.” Stewart, who was primarily responsible for the creation of this outlaw myth, died in Wharton, Texas, in 1854. Murrell’s life was fictionalized by the famed Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges in “The Cruel Redeemer Lazarus Morell,” the first story in his 1935 collection A Universal History of Infamy.

For additional information:

Ball, Larry D. “Murrell in Arkansas: An Outlaw Gang in History and Tradition.” Mid-South Folklore 6 (Winter 1978): 65–75.

Dickinson, Sam. “The Murrell Gang: Arkansas’ First Great Outlaw and His Desperado Clan.” Arkansas Times, October 1984, 46–49, 79–80, 82–83.

Penick, James Lal, Jr. The Great Western Land Pirate: John A. Murrell in Legend and History. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1981.

Larry D. Ball

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Folklore and Folklife

Folklore and Folklife Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 John A. Murrell Article

John A. Murrell Article

“A most atrocious and diabolical wholesale murder and robbery had been committed on the Arkansas side. The crew of a flatboat had been murdered in cold blood, disemboweled, and thrown in the river, and the boat-stores appropriated among the perpetrators of the foul deed. The Murrell Clan was charged with the inhuman and devilish act. Public meetings were called in different parts of the country to devise means to rid the country and clear the woods of the Clan, and to bring to immediate; punishment the murderers of the flatboat men. In Covington a campaign was formed to that end, under the command of Maj. Hockley and Grandville D. Searcey, and one, also formed in Randolph, under the command of Colonel Orville Shelby A flatboat, suited to the purpose, was procured, and the expedition consisting of some eighty or an hundred men, well armed, with several day’s rations, floated out from Randolph, and down to the landing where wholesale murder had been committed. Their place of destination was Shawnee Village, some six or more miles from the Mississippi. Where the sheriff of the county resided. They were first to require of the sheriff to put the offenders under arrest and turn them over to be dealt with according to law. To the Shawnee Village the expedition moved in single file, along a tortuous trail through the thick cane and jungle, until within a few miles of the village, when a shrill whistle at the head of the column startled the whole line. Answered by the sharp click! click! click! of the cocking of the rifles in the hands of Clansmen. In ambush, to the right flank of the moving file, and within less than a dozen yards.

The chief of the Clan stepped out at the head of the expedition, and in a stentorian voice commanded the expedition to halt, saying:

“We have man for man; move forward another step and a rifle bullet will be sent through every man under your command.”

A parley was had, when more than man for man of the Clansmen rose from their hiding places in the thick cane, with their guns at present. The expedition had fallen into a trap; the Clansmen had not been idle in finding out the movements against them across the river. Doubtless many of them had been in attendance at the meetings held for the purpose of their destruction. The movement had been a rash one, and nothing was left to be done but to adopt the axiom that “prudence is the better part of valor.” The leaders of the expedition were permitted to communicate with the sheriff, who promised to do what he could in having the offenders brought to justice; but alas for Arkansas and justice! The Sheriff himself was thought to be in sympathy with the Clan. And law was in the hands of the Clansmen. The expedition retraced their steps. Had it not been so formidable and well known by the Clansmen, every member of it would have found his grave in the Arkansas swamp.” (From Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/10350054/john-andrews-murrell, quoted from Botkin, p. 214)

My family owned Shawnee Village for about thirty years. I hunted all over looking for anything he could have buried. Including a old cemetery dated back to the 1820s. I never used a metal detector there but looked at what headstones were left.

A part of this family relocated to Ontario, Canada, in the mid-to-late 1800s. In 1960, it was of one family, with cousins in Alberta. There were very few Murrells in Canada, and they were aware of each other. There was land in Kansas that was sold in the 1950s, which was owned previously by ancestors of the Murrells in Canada. Most are buried in one graveyard north of Toronto. We are aware though elders in the family to be direct descendants to John Andrews Murrell. Link, however, is lost outside of a couple of very old pictures, and carved initials on a pre-1900 grave, having importance to my grandfather and deceased father.