calsfoundation@cals.org

Jeff Davis (1862–1913)

Twentieth Governor (1901–1907)

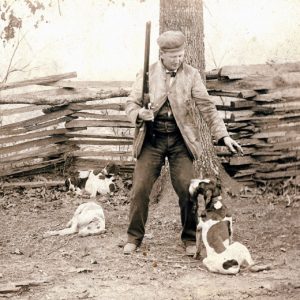

Jeff Davis was a populist governor who railed against corporations and often resorted to race baiting in his campaigns. His tenure in office proved extremely divisive, creating for him many enemies. However, Davis dominated Democratic politics in the state in the early years of the twentieth century, being elected to the office of governor three times and going on to become a U.S. senator.

Jeff Davis was born on May 6, 1862, near Rocky Comfort (Little River County) to Lewis W. Davis, a Baptist preacher, lawyer, and county judge, and Elizabeth Phillips Scott. Named for the president of the Confederacy, Davis enjoyed a relatively privileged childhood. In 1869, his family moved to Dover (Pope County) and then, in 1873, moved to nearby Russellville (Pope County). He spent two years at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) before transferring to Vanderbilt University, where he completed the two-year law program in one year but was not granted a diploma because he failed to meet the residency requirement. Through his father’s influence, however, he was admitted to the state bar at age nineteen. He later completed his law degree at Cumberland University in Tennessee in 1881 and became the junior partner of his father’s law firm.

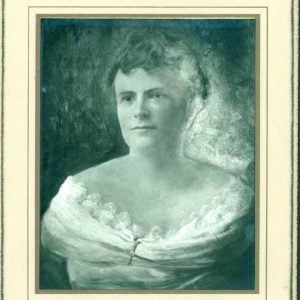

In October 1882, Davis married Ina MacKenzie. She bore twelve children, eight of whom survived past infancy. She died in 1910, and a year later, Davis married Leila Carter of Ozark (Franklin County).

Selected as a presidential elector by the state Democratic convention, Davis stumped in 1888 for President Grover Cleveland, white supremacy, and “reform.” In 1890, he ran for district prosecuting attorney and narrowly won the Democratic nomination. Unopposed for reelection in 1892, he served until October 1894. Two years later, after giving up on a bid for Congress due to Pope County’s mixed support for his run, he became absorbed in the 1896 presidential campaign of William Jennings Bryan, again serving as a presidential elector for a time.

In 1898, Davis was elected state attorney general when the front-runner, Judge Frank Goar, suffered a fatal stroke. Davis became the most controversial and memorable attorney general in state history. By challenging the legality of the Kimball State House Act, which provided for construction of a new capitol building on the site of the existing state penitentiary, and by rendering a controversial extraterritorial interpretation of the Rector Antitrust Act, he triggered a series of political controversies. According to Davis, the Rector Act prohibited any trust from doing business in Arkansas, regardless of where it had been organized. In March 1899, he sued every fire insurance company doing business in the state, demanding that they withdraw from industrywide pricing agreements. The companies threatened to cancel policies by the hundreds, and outraged businessmen held protest meetings. Davis, supported by the state legislature, refused to back down, but the state Supreme Court overruled his interpretation.

In June 1900, he announced his candidacy for governor and embarked on a year-long campaign, visiting nearly every county. “The war is on,” he declared, “knife to knife, hilt to hilt, foot to foot…between the corporations…and the people.” Although the state press ridiculed him, and his four opponents branded him a demagogue, he won the most resounding political victory in state history, carrying seventy-four of seventy-five counties in the primary.

Davis’s governorship was marked by factionalism and polarization. In his first term, the most divisive issues were penal reform and the construction of a new statehouse. When the penitentiary buildings were demolished in the summer of 1899 to make way for the statehouse, the penitentiary board (made up of the governor and four other state officials) had to find a new home for several hundred inmates. The board leased nearly a third of the state’s prisoners to a ten-year contract, even though long-term convict-lease contracts violated state policy. Davis, for political and humanitarian reasons, demanded that the contract be annulled. Meanwhile, the legislature issued a mandate to begin building the new statehouse, but Davis unveiled his own plans to build on the foundation of the old statehouse. Critics charged that Davis knew his proposal was unrealistic and was using it to further postpone construction of a statehouse on the penitentiary grounds.

Davis’s handling of these issues left many Democratic leaders disgruntled, but the controversy that most shook the state party was his interference in the Senate race between incumbent James K. Jones, former chairman of the Democratic National Committee, and former governor James Paul Clarke. Ignoring an unwritten party rule against mixing gubernatorial and senatorial politics, Davis threw his support to Clarke, east Arkansas’s most powerful politician. Davis said Jones, who owned stock in the American Cotton Company, was a tool of the trusts. Jones and others persuaded Elias W. Rector, who had sponsored the 1899 antitrust act, to challenge Davis in the 1902 gubernatorial primary.

In the tumultuous campaign that followed, Davis emphasized Rector’s aristocratic background (his father was former governor Henry Massie Rector). But he eventually focused on Rector’s involvement in a conspiratorial “penitentiary ring,” an issue that had more to do with racial demagoguery than penal reform. Rector charged that Davis was a drunkard and a tool of the liquor interests. However, Davis won 66.1 percent of the vote.

In April 1902, a disciplinary committee at Second Baptist Church in Little Rock (Pulaski County) that included state Supreme Court justice Carroll Wood drew up a list of charges against Davis, accusing him of public drunkenness, chronic intemperance, and generally immoral behavior. Davis condemned the proceedings as a political witch-hunt, but in May, he was expelled from the congregation, an act that further polarized the state Democratic Party. Davis had previously resigned from his position as vice president of the Arkansas Baptist State Convention, to which he had been elected in 1901, after a feud with former governor and association president James Philip Eagle.

In January 1903, Davis devoted almost half of his inaugural address to criticizing the penitentiary board’s purchase of a tract of farm property, which he insisted was “unfit for a convict farm.” His attack led to an impeachment campaign. Despite an investigation, the effort failed. In the last weeks of the legislative session, Davis’s enemies dealt him one defeat after another, but this only steeled his defiance. In May, after announcing his intention to run for a third term, he issued an omnibus veto of more than 300 bills.

This set the stage for a tumultuous primary campaign, as Wood and two other challengers tried to put an end to “Jeff Davisism.” With the anti-Davis press mobilized as never before, the state was flooded with anti-Davis broadsides and pamphlets, rallies, and parades. Although Wood was the self-professed candidate of moderation and respectability, both sides resorted to demagoguery and personal invective, and on two occasions, the two candidates came to blows. Wood charged that Davis was morally unfit to be governor. Davis, relying on folksy rhetoric and a sharp wit, portrayed Wood as a dandified, trust-heeling city slicker. Davis won with 57.8 percent of the vote.

In his third term, Davis gained control of the legislature, which approved several of his pet projects, including an antitrust law and the reorganization of penitentiary management. But he continued to devote most of his time to political matters. In 1905, he challenged a former ally, U.S. senator James Henderson Berry, a Confederate veteran who had served in the Senate since 1885. In the senatorial primary, Berry was no match for the governor, especially after President Theodore Roosevelt visited Little Rock in October 1905. Davis turned the president’s visit into a white supremacist publicity stunt by devoting most of his welcoming speech to a defense of lynching. Refusing to attend a banquet in Roosevelt’s honor because former governor Powell Clayton had been invited, Davis turned the event into a major political issue. Despite his status as one of the last surviving Confederate officers, Berry was branded a traitor to the South for having attended the banquet. Davis defeated Berry in the 1906 primary.

Davis’s elevation to the Senate was a Pyrrhic victory, leading to a senatorial career that was little more than a “long anti-climax,” as one historian put it. The rough-and-tumble style of political combat that had been so effective in the back country seemed out of place in the nation’s capital. Soon after he arrived in Washington DC, he introduced an antitrust bill and delivered a long and impassioned harangue against “the malefactors of great wealth.” The speech drew criticism from the national press and several Senate colleagues. In April 1908, in an effort to get his antitrust bill out of committee, Davis apologized for his intemperate rhetoric and breach of senatorial etiquette, but it was too late. The press continued to portray him as a wild-eyed, backwoods buffoon, and he retreated into silence.

During his years in the Senate, a deteriorating power base in state politics compounded Davis’s problems. Determined to regain control of the governorship, less than two months after arriving in Washington he returned to Arkansas to campaign for his close friend Attorney General William F. Kirby, who was seeking the Democratic nomination. Kirby’s major opponent, George Washington Donaghey, was a prominent building contractor and progressive who was difficult to demonize. Despite Davis’s monumental stump speaking effort, Kirby was soundly defeated, dealing the Davis organization an electoral setback from which it never recovered.

Davis spent the rest of his career brooding about his lack of influence in Little Rock and Washington. In 1910, after supporting William Kavanaugh’s unsuccessful gubernatorial bid, Davis became embroiled in a controversy over the disposition of public land in east Arkansas. This apparent collusion with land speculators in the sunken lands controversy tarnished his reform image and accelerated his political decline. During his final years in the Senate, he spent less and less time in Washington. He barely survived a challenge from Representative Stephen Brundidge in 1912.

Davis’s reelection seemed to rekindle his interest in Washington and public policy, but his comeback was short lived. On January 3, 1913, two months before the expiration of his first term, Davis suffered a fatal stroke. His was one of the largest funerals in Little Rock history; thousands of mourners paid respects. He is buried at Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Arsenault, Raymond. The Wild Ass of the Ozarks: Jeff Davis and the Social Bases of Southern Politics. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Jacobson, Charles. The Life Story of Jeff Davis. Little Rock: Parke-Harper, 1925.

Ledbetter Jr., Cal. “Jeff Davis and the Politics of Combat.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 33 (Spring 1974): 16–37.

Meriwether, Robert W. “Jeff Davis and Faulkner County Politics (1900–1908).” Faulkner Facts and Fiddlings 32 (Spring/Summer 1994): 8–27.

Mulhollan, Paige E. “The Issues of the Davis-Berry Senatorial Campaign of 1906.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20 (Summer 1961): 118–126.

Niswonger, Richard L. “Arkansas Democratic Politics, 1896–1920.” PhD thesis, University of Texas, 1973.

Raymond O. Arsenault

University of South Florida

Staff of the Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.