calsfoundation@cals.org

Jazz Music

With New Orleans, Louisiana, and Kansas City, Missouri, emerging as the booming urban epicenters of jazz music and inevitably spilling this music and culture across interstate lines, Arkansas began to see a number of touring “territory bands” sprout up around the state in the late 1910s and early 1920s. Some of the first included Sterling Todd’s Rose City Orchestra; the Quinn Band out of Fort Smith (Sebastian County); and the Synco Six out of Helena (Phillips County), led by banjo player Gene Crooke.

All three bands were at some point joined by Arkansas’s first major jazz musician, pianist Alphonso E. “Phonnie” Trent. Trent played with the Rose City Orchestra and the Quinn Band during his teenage years before eventually taking over Gene Crooke’s Synco Six in 1923 and changing the band’s name to the Alphonso Trent Orchestra.

By 1925, the band had found a residency at the Adolphus Hotel in Dallas, Texas, becoming the first Black musicians to be broadcast on the radio (on Dallas’s 50,000-watt WFAA-AM). It was, according to jazz historian Gunther Schuller, “the most idolized and advanced band of the Southwest.” The band also featured two of Arkansas’s most talented early jazz artists: Lawrence Leo “Snub” Mosley of Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Hayes Pillars of North Little Rock (Pulaski County). Snub Mosley was a jazz trombonist, composer, and band leader whose career spanned more than fifty years, which included stints in the 1930s with Claude Hopkins, Fats Waller, and Louis Armstrong. Mosley is probably best remembered today as creator of his own unique instrument—the slide saxophone. Saxophonist Hayes Pillars would, in 1934, alongside James Jeter, take control of the Alphonso Trent Orchestra and later form the Jeter-Pillars Orchestra.

Around this time, Arkansan Eugene Staples (born in 1893) began the notorious hot jazz band Blue Steele and His Orchestra in Atlanta, Georgia, enlisting tenor saxophonist Pat Davis of Little Rock. In 1925, future icon Louis Jordan began making a name for himself playing alto saxophone in Brady Bryant’s Salt and Pepper Shakers out of Brinkley (Monroe County).

The mid-to-late 1920s also saw an emergence of jazz in El Dorado (Union County), driven by the number of dance halls popping up in the wake of the city’s oil boom. There, Jordan played briefly in Jimmy Pryor’s Imperial Serenaders, one of a number of El Dorado bands whose short tenures were a result of the city police’s crackdown on Prohibition-era nightclubs.

The 1930s saw several music venues emerge around central Arkansas, hosting some of the biggest national names in jazz. The Cinderella Gardens and Dance Palace, the Dreamland Ballroom in Taborian Hall, and the Mosaic Temple, all in Little Rock, became frequent stops for the leading bands in the Southwest as well as national artists such as Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole, and Duke Ellington.

While Little Rock was becoming a major regional hub for star acts, a student at the Arkansas School for the Blind, Al Hibbler, began singing in local bands, eventually joining Jay McShann’s orchestra in Kansas City for a year and a half in 1942–43 before moving on to front Duke Ellington’s band for the next eight years, where he found national success and critical acclaim as a voice that bridged the styles of jazz and rhythm and blues (R&B).

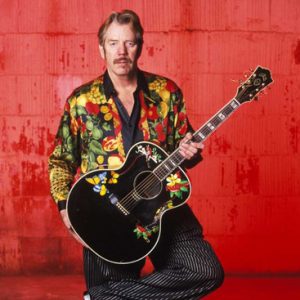

Two of the most idiosyncratic, forward-thinking figures in 1950s jazz have Arkansas connections, as well. The first is Bob Dorough, born in Cherry Hill (Polk County), who is best known as the composer and voice of Schoolhouse Rock!. However, in 1954, Dorough was hired by boxer Sugar Ray Robinson. Robinson, who was taking a break from the ring to star in a song-and-dance revue, brought in Dorough as the show’s music director. Over the following years in Paris, France, Dorough performed nightly gigs at a famous Parisian jazz mainstay, the Mars Club; performed with Louis Armstrong and Count Basie; recorded with fellow “hip vocalese” singer Blossom Dearie; and released Devil May Care, his first of several albums.

The second key 1950s figure is Louis Thomas Hardin, who spent his late teens and early twenties in Batesville (Independence County), enrolling at Arkansas College (now Lyon College) for one year, before moving to New York City in 1943 at the age of twenty-seven. There, the young eccentric pianist took the name Moondog and began dressing like the Norse god Odin, earning him the nickname “the Viking of Sixth Avenue.” An experimentalist to the core, Moondog fused third-stream jazz and classical minimalism, earning the praises of, notably, Charlie Parker, Charles Mingus, and Philip Glass.

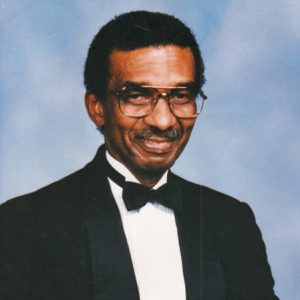

Another Arkansan to fuse jazz and classical styles, Walter Norris, has been hailed by some jazz historians as one of the greatest jazz pianists of all time. A key member of the West Coast jazz scene of the late 1950s, Norris played piano on the ground-breaking album Something Else!: The Music of Ornette Coleman (1958), joined the Charles Mingus Quintet in 1976, and, in between, served as the director of entertainment for the New York City Playboy Club from 1963 to 1970.

One of the biggest names in Arkansas’s jazz history is pianist Arthur Lee (Art) Porter Sr., who performed mostly within the state. A vocal teacher by day and jazz pianist by night, he founded the popular Art Porter Jazz Trio. He hosted a musical variety program, The Minor Key, on the Arkansas Educational Television Network, which began in 1971 and lasted for a decade. Another program, Porterhouse Cuts, was a series of ten shows that aired in thirteen states. His son Art Porter Jr. of Little Rock was a creative composer whose work ranged across jazz, rhythm and blues, funk, and ballads.

While the melding of classical and jazz forms has been a major trend throughout Arkansas’s jazz history, Pharoah Sanders, born Ferrell Sanders in Little Rock, is one of the major founding figures of the decidedly anti-classical/formalist free-jazz movement. While still enrolled at Scipio Jones High School in North Little Rock in the late 1950s, Sanders was a regular at Little Rock’s downtown jazz clubs. After a brief stint in San Francisco, California (where he was known as “Little Rock”), Sanders relocated to New York in 1961, where he played with a number of jazz luminaries, including Sun Ra and Don Cherry. By 1965, Sanders was collaborating extensively with John Coltrane, influencing Coltrane with his deconstructive, free-jazz dissonance. Between 1966 and 1971, Sanders released five albums that are considered defining points of the free-jazz movement: Tauhid (1966), Karma (1969), Deaf Dumb Blind (Summum Bukmun Umyun) (1970), Thembi (1971), and Black Unity (1971).

Arkansas’s continuing interest in jazz can be seen through the number of local jazz festivals that began popping up around with state, with the Eureka Springs Jazz Festival being founded in 1984 and the Hot Springs Jazz Fest following in 1992.

The Arkansas Jazz Heritage Foundation was established in the early 1990s to “educate the general public about the historical significance of Arkansas’s musical heritage” through organizing weekly jazz sessions and, since 1994, maintaining the Arkansas Jazz Hall of Fame, which regularly honors Arkansans of note in the field of jazz. Members of the Arkansas Jazz Hall of Fame include Phonnie Trent, Al Hibbler, Bob Dorough, Clark Terry, and Art Porter Jr. The following artists are members of both the Arkansas Jazz Hall of Fame and the Arkansas Entertainers Hall of Fame: Art Porter Sr., Louis Jordan, Pharoah Sanders, and Walter Norris.

For additional information:

Arkansas Jazz Heritage Foundation. http://www.arjazz.org/ (accessed June 27, 2025).

Cochran, Robert. Our Own Sweet Sounds: A Celebration of Popular Music in Arkansas. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

Kernfield, Barry. The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz. New York: Grove’s Dictionaries, 2002.

Rice, Marc. “Frompin’ in the Great Plains: Listening and Dancing to the Jazz Orchestras of Alphonso Trent, 1925–44.” Great Plains Quarterly 16 (Spring 1996): 107–115.

Rinne, Henry. “A Short History of the Alphonso Trent Orchestra.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 45 (Autumn 1986): 228–249.

John Tarpley

Dallas, Texas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.