calsfoundation@cals.org

Hot Springs Fire of 1913

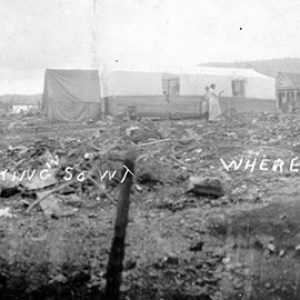

The Hot Springs Fire of 1913 was one of the most destructive in Arkansas history. It caused $10 million in damage, destroyed twenty acres of Hot Springs (Garland County), and left more than 2,500 people homeless.

By 1910, Hot Springs was one of the most important cities in the region and the pre–Civil War population of 201 had exploded to 14,434. Many travelers also visited the town and the National Park. People from all over the world came to bathe in the city’s hot spring water, thought to have healing properties, but many also partook of the town’s illegal gambling and prostitution. In a state best known for rural poverty, Hot Springs was a rare island of wealth and modernity.

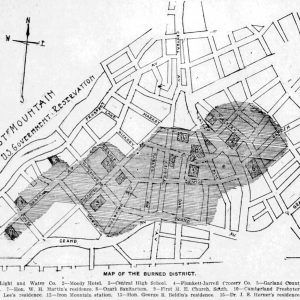

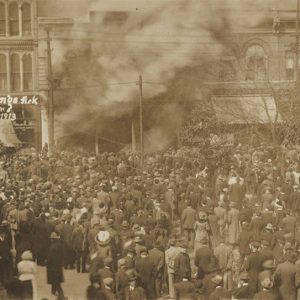

Just before 2:15 p.m. on Friday, September 5, 1913, Ulma Madlock was ironing in her home on Church Street when the iron ignited a curtain flowing in an afternoon breeze. (Today, a parking lot for the Hot Springs Convention Center stands on the site of the Madlock home.) Within minutes, fire engulfed the house. An observer reported the blaze to the fire department. Fire Chief Henry Higgins helped his men hitch up the hand-cranked pump wagon to a team of horses, and within minutes they were racing toward the rapidly growing inferno. The firemen immediately realized that they needed reinforcements. The fire had already spread from Madlock’s home to nearby houses in the tightly packed neighborhood of wooden homes. The fire burned southeast as it destroyed homes on Church, Laurel, Pleasant, Garden, and Grove streets. In a desperate bid to halt the fire’s progress, a group of men led by city treasurer George Housley blew up the People’s Laundry at 356 Malvern Avenue with a pack of dynamite, but the blast did not slow the blaze.

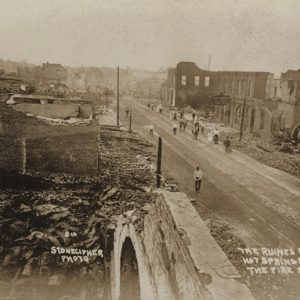

About an hour after the blaze began, the fire split into two, simultaneously spreading up and down Malvern Avenue. The fire destroyed the city’s electric generation plant, depriving the town of electric service and leaving people stranded in elevators and street cars. Gale-force winds swept through the town, raining burning debris onto rapidly igniting homes and showering panicking pedestrians with burning ashes. By now, virtually every able-bodied man in the city was trying to help the firefighters, but just as the full weight of the city’s manpower came into action, pipes burst in destroyed buildings, which reduced the city’s water pressure to a trickle. Firehoses melted under the intense heat, and firefighters became little more than spectators to the inferno.

At 8:00 p.m., firefighters and equipment arrived by train from Little Rock (Pulaski County). The people of Hot Springs were grateful for the assistance, but the Little Rock firefighters could do little to stop the blaze, since fire hoses from Little Rock did not fit the Hot Springs fire hydrants. The wind finally died down in that evening, and the fire began to subside. A thunderstorm put out the final remnants of the blaze the next morning.

Hot Springs rebuilt quickly after the fire. Modernized electrical and telephone systems replaced the ones that were destroyed. The popular wooden-shingled roofs that had burned so readily were outlawed. Hot Springs doubled the size of the fire department and purchased the best equipment money could buy, preventing devastating fires like the one in 1913.

For additional information:

Blythe, Mike, and Clyde Covington. “City in Flames: The Fire of 1913.” The Record (2013): 1.1–1.28.

Cockrell, Ron. The Hot Springs of Arkansas, America’s First National Park: The Administrative History of Hot Springs National Park. Washington DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2014.

Covington, Clyde. “Grandeur in Flames: Malvern Avenue’s Park Hotel.” The Record (2025): 4.1–4.14.

Paige, John C., and Laura E. Soullière. Out of the Vapors: A Social and Architectural History of Bathhouse Row: Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas. Washington DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1988.

Christopher Thrasher

National Park College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.