calsfoundation@cals.org

Hemp Neal (Lynching of)

An African-American man named Hemp Neal was lynched on November 5, 1878, outside of Clarksville (Johnson County) for allegedly raping a young white woman. This was the first recorded lynching in Johnson County.

The identity of Neal is difficult to determine. His name is also given as Hamp Neal, or simply as Neely, in various reports. The Clarksville Herald, in an article reprinted in the Arkansas Gazette, described Neely (the name it gave him) as a “burly negro…who is a newcomer to our neighborhood.” The Arkansas Democrat reported his name as Hemp Neal, specifying that he was about twenty-five years old and “came here last March from Louisiana.” He apparently worked on the farm of one Dr. Adams, two miles from Clarksville. One possible match on the 1870 census is Hamp Nail, then living in North Carolina. He was eighteen years old in 1870 and working as a railroad laborer, and his name does not appear in the 1880 census (though this is no guarantee for an exact match, as censuses varied in quality and accuracy). Had he continued in the line of railroad labor, he may have ended up in Johnson County working on the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad and perhaps found another job while in the area.

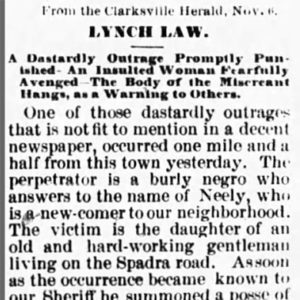

His crime was described by the Clarksville Herald as “one of those dastardly outrages that is not fit to mention in a decent newspaper,” but the Democrat was less circuitous, naming his crime as rape, adding that Neal was reportedly on his way to Clarksville “to visit some friends when he committed the outrage.” While the Herald describes his ostensible victim as “the daughter of an old and hard-working gentleman living on the Spadra road,” the Democrat, again, is more specific, naming the victim as Mrs. Salona Hann and her father as Mr. Haskel. There are good matches in the 1880 census for these names, for one Sarah L. Hanes, age twenty-five in 1880, is recorded as a widow living at the house of her father, Samuel Haskell, a Spadra farmer, along with her daughter, Phebe Ann, then aged three.

The Democrat goes into salacious detail regarding the alleged rape, reporting that Neal, on November 4, stopped at the Haskell residence to ask for a drink of water. Learning that Haskell had not yet returned from work, and seeing that Hanes was alone with only her small child, “he determined to take advantage of her position to carry out his hellish designs.” Neal, after choking her and forcing her to the floor, “accomplished his purpose and fled, leaving his victim almost dead from the injuries he inflicted.”

According to the Herald, when the “occurrence” became known to Sheriff E. T. McConnell, a posse was organized, and Neal was swiftly apprehended. The Democrat, again, offers a more detailed story, stating that Haskell informed the sheriff, who, “in company with Mr. McBrown,” pursued Neal. They found him “in a shanty in company with several other negro men and women…enjoying himself immensely,” but Neal fled from this site and was only overtaken after a brief pursuit and struggle.

On the evening of November 4, threats of lynching began to be expressed. However, the sheriff was able to maintain order for the time being, and “things settled down quietly, apparently for a little while.” By the following evening, groups of men were seen assembling in town; although the sheriff was described as determined to defend his prisoner, it was noted that “he had to do with men equally determined to avenge the most heinous insult that could be perpetrated against woman.”

At 7:35 p.m., on November 5, the mob began entering the courthouse, and its members “overpowered and bound” the sheriff, disarmed the guards, and took Neely about a mile outside of town, where they hanged him from a tree. The Clarksville Herald, in the manner of many newspapers at the time, editorialized on the lynching by blaming its victim: “We deeply regret the whole occurrence—regret that anything in the form of man could be guilty of such an act. But the first act in the tragedy having been committed, and the proof being so conclusive as not to leave a shadow of doubt, we will not be so hypocritical as to say we condemn the men who performed the hanging of this man.”

For additional information:

“The Clarksville Outrage.” Memphis Daily Appeal, November 17, 1878, p. 2.

“A Damnable Crime.” Arkansas Democrat, November 5, 1878. p. 1.

“Lynch Law.” Arkansas Gazette, November 8, 1878, p. 1.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.