calsfoundation@cals.org

Guy v. Daniel

aka: Abby Guy v. William Daniel

Abby Guy v. William Daniel was a freedom suit and racial identity case brought before the Arkansas Supreme Court in January 1861. The case originated in the Ashley County Circuit Court in July 1855 when Abby Guy sued William Daniel, whom she said wrongfully held her and her children in slavery. According to Guy, she and her family were free white people. After a jury decided in favor of Guy, Daniel appealed the case to the Arkansas Supreme Court, which, in the end, declined to overturn the lower court’s verdict. Guy and her children were freed. Racial identity trials, in which the outcome rested on whether or not one party was white, were not unusual in the South. Guy v. Daniel, as an example, provides a window into how people at that time viewed race and freedom, and how race and racial identity were constructed in the Old South and frontier areas such as Arkansas.

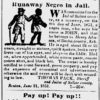

Abby Guy’s family had lived in Ashley County as free people since 1844, and the 1850 federal census identified them as free people of color. Guy supported her family by farming, and she socialized with the white people in the community as a free white woman would. It was not until Guy decided to move to Louisiana in 1855 that Daniel seized the family and started to hold them as slaves. Consequently, Guy sued Daniel in circuit court to hold on to the freedom that her family had exercised over the previous years.

Guy professed that her mother had been a white orphan in Virginia and had been wrongfully sold into slavery to Daniel’s father in Alabama. Sometime over the years, Nathaniel Daniel, William’s brother, acquired ownership of Abby Guy. Guy claimed that Nathaniel manumitted her in his will but that William Daniel ignored his brother’s wishes and held her in bondage. As the owner of 240 acres of land and fifteen slaves, William Daniel was one of the most prominent slaveholders in Ashley County. Additionally, he served as a justice of the peace and postmaster.

To defend his claim on Guy’s family, Daniel presented Nathaniel’s will, which made no mention of Abby. Daniel admitted to allowing Guy to live without supervision for several years because, he said, she was not useful as a slave. His case relied on documentation to prove that the Guys were his lawful property. It also relied on the logic that since Abby Guy was a slave, she could not be white.

Guy used the accounts of members of the community, who testified that she and her family had lived as free white people and had socialized and behaved accordingly. Much of the testimony depended on the assumption that white southerners had the ability to recognize signs of “negro blood” even in fair-skinned people of mixed descent. The Guy family also submitted to physical inspection in the courtroom to allow the examination of their bodies to determine whether there were signs to indicate that they were of African lineage. Although the preponderance of documented evidence seemed to favor Daniel, juries—who were swayed by Guy’s reputation and her successful adherence to the kind of behavior that Southern society expected of a white woman—ruled in her favor.

Upon Daniel’s final appeal before the Arkansas Supreme Court, the court’s justices dismissed Daniel’s technical objections about the latest jury decision against him. Although the court did allow that the jury may have “found against the preponderance of evidence,” it refused to overturn the jury’s decision, due in part to “reluctance to sanction the enslaving of persons” who appeared to be white and had lived as free white people for years. Abby Guy and her children were set free.

Interestingly, the legal disputes pitted attorney Augustus Hill Garland, future governor of Arkansas, against attorney James Yell, who was a state legislator who served as a major general in the Arkansas State Militia during the Civil War. Garland represented Abby Guy in the cases before the Arkansas Supreme Court, and Yell represented slave owner William Daniel in three jury trials and two appellate cases at the Arkansas Supreme Court.

In the decade preceding the Civil War, abolitionists and Northern newspapers made much ado about “white slaves” in the South. Southerners used racial identity trials like that of Abby Guy to argue that legal systems in the South corrected the error when any white person might have the misfortune to wrongly fall into bondage.

For additional information:

Gross, Ariela J. “Litigating Whiteness: Trials of Racial Determination in the Nineteenth-Century South.” Yale Law Journal 108 (October 1998): 109–188.

———. What Blood Won’t Tell: A History of Race on Trial in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

Mahan, Russell. Abby Guy: Race and Slavery on Trial in an 1855 Southern Court. Santa Clara, UT: Historical Enterprises, 2017.

Shafer, Robert S. “White Persons Held to Racial Slavery in Antebellum Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 44 (Summer 1985): 134–155.

Zackodnik, Teresa C. The Mulatta and the Politics of Race. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2004.

Kevin D. Butler

University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.