calsfoundation@cals.org

Morrison v. White

Morrison v. White was a case involving slavery in which, after numerous legal twists and turns, Jane/Alexina Morrison, who claimed to be a free white woman from Arkansas, was granted her freedom by a Louisiana district court jury in 1862. As did several other freedom suits of the time (such as Guy v. Daniel and Gary v. Stevenson), this one went well beyond the usual issue of ownership and addressed the fundamental question of who could, in fact, be enslaved—and, in particular, whether a white person could be a slave. Unlike the famous case of Dred Scott, a black man whose claim to freedom was based on his residence in a statutorily free area of the country, Jane/Alexina Morrison rested her claim to freedom on the fact that as a white person—which to all appearances she was—she could not be enslaved.

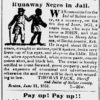

The case began in 1857 when J. A. Halliburton, a resident of Arkansas, sold Jane Morrison, a fifteen-year-old girl, to a slave trader named James White of New Orleans, Louisiana. Apparently, Morrison, described in all accounts as blond-haired and blue-eyed, soon ran away from White, only to reappear in October 1857 when she filed a lawsuit in the Third District Court in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, just up the Mississippi River from New Orleans. In the suit, Morrison said that she was white, that she had never been a slave, and that her real name was Alexina Morrison. Her petition also requested that the jailer of Jefferson Parish, William Dennison, be appointed her guardian, and that in the meantime she be allowed to remain in the parish prison so that she could not be seized by White and resold.

The suit devolved into a series of charges and countercharges between Halliburton and White. Halliburton’s bill of sale to White was not notarized, something that was illegal in Louisiana but not in Arkansas. Meanwhile, the accused White counter-sued the jailer, William Dennison, charging him with stealing and harboring a runaway slave.

In the end, the case came down to a determination of Morrison’s race, a judgment based as much as anything on what she looked like and how she behaved, the central determinants to whether or not she was white. While technically a series of legal proceedings, the case was in fact a local microcosm of a divided nation’s views and assumptions about race and racial identification. In that way, Morrison v. White encompassed the continuing American struggle to deal with issues of race.

Questions arose about Jane/Alexina Morrison. Records from the 1850 census appear to place the seven-year-old girl in Matagorda County, Texas, one of five children who, like their mother, were listed as “mulatto” slaves. The identity of her father is unknown. Her slavery designation notwithstanding, there was no definitive evidence of Jane/Alexina Morrison’s status or how she was treated as a member of the Morrison household in the years until 1857, when she was sold from a New Orleans slave pen to James White. Whether she was treated as a member of the family or as a slave remains unknown, but it is clear that when White bought her, he bought a slave; when she later escaped, she was, at least in her mind, a white woman who could not be legally enslaved.

Over the course of three separate trials, extensive efforts were undertaken by Morrison’s attorneys to prove her status as a white person who should be free, but efforts to contact old friends and family in Arkansas and Texas were unsuccessful. In the end, Morrison and her attorneys relied on what they saw as a fundamental truth: she was white because she looked and acted white. White and his attorneys were able to piece together a more comprehensive story, one buttressed by testimony from people who remembered her as a young girl, as well as testimony from Moses Morrison, who remembered buying her mother and the children in 1848 but was unclear about what happened after he gave the girl to his nephew shortly after the 1850 census. According to most legal standards of the time, the basically agreed upon sale of Jane/Alexina to Moses Morrison back in 1848 made her a slave. However, her assertion that she white, an assertion supported by its apparent visual correctness, was a powerful argument in her behalf.

The opposition engaged in aggressive cross-examination, as well as numerous pseudo-science-based efforts aimed at forcing her alleged “black blood” to emerge, subjecting Morrison to a physical examination as invasive as those to which slaves on the auction block were often subjected. In the end, however, there was little to convince observers or jurors that the plaintiff sitting before them was anything but white because she looked and acted as people expected whites to do.

After the first trial ended in a mistrial, a second one was convened in May 1859. This time, a jury unanimously ruled that Alexina Morrison should be free. White and his attorneys appealed to the state Supreme Court, which ordered a third trial determining that evidence of the girl’s sale to Moses Morrison, as well as depositions from Texas and Arkansas, had been improperly excluded. Finally, before a third jury, hearing the case in January 1862, a 10–2 verdict gave Alexina Morrison her freedom. White’s lawyers again appealed to the state Supreme Court, but that appeal was never acted upon.

For additional information:

Holt, Thomas. “Understanding the Problematic of Race through the Problem of Race Mixture.” http://www.understandingrace.org/resources/pdf/myth_reality/holt.pdf (accessed September 21, 2020).

Johnson, Walter. “The Slave Trader, the White Slave, and the Politics of Racial Determination in the 1850s.” Journal of American History 87 (June 2000): 13–38. Online at http://www.uvm.edu/~psearls/johnson.html (accessed September 21, 2020).

William H. Pruden III

Ravenscroft School

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Law

Law Slave Resistance

Slave Resistance

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.