calsfoundation@cals.org

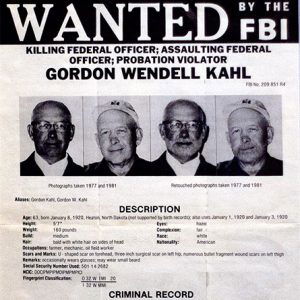

Gordon Kahl (Shooting of)

aka: Smithville Shootout

Gordon Kahl was a North Dakota farmer and World War II veteran who, starting in the late 1960s, refused to file his federal income taxes on the grounds that the American government operated under the Communist Manifesto and violated his religious principles. After over a decade of militant tax evasion and a year in prison, Kahl was shot during an attempted arrest in Smithville (Lawrence County) by County Sheriff Gene Matthews in an incident that made national headlines as the “Smithville Shootout.” Kahl’s life and the circumstances of his death have since become a popular subject for conspiracy theorists and those on the far right of the political spectrum.

Gordon Wendell Kahl was born in 1920 in Heaton, North Dakota, to Frederick and Edna Kahl. He graduated from high school in 1938 and served in World War II as a turret gunner for the Army Air Corps. Upon returning home, he married Joan Seil, who was from his hometown, with whom he raised two sons and four daughters. He worked off and on as a mechanic, and realized during this time his grudge against the federal government, especially against the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). He believed that since the IRS was part of the executive branch, it violated the separation of powers because the framers of the Constitution, according to Article I, Section 8, had intended taxation to be carried out by Congress, in the legislative branch. His opinions of the government had a strong connection to his religious values; he had been raised in the Congregationalist Church and, according to his daughter Lorna, believed that if he paid his taxes he would be sent to hell.

In 1977, Kahl was sentenced to two years in prison and five years probation for not filing his federal income taxes for the years 1973 and 1974. He served only eight months and, after his release, again failed to file his taxes; he also lived briefly in Texas with his wife and became more involved with the Posse Comitatus, a localist organization whose members believe that the power of the county supersedes that of the Constitution. Because tax evasion and moving across state lines without authorization constituted a violation of his probation, the IRS seized his eighty-acre property.

The first shootout in which Kahl was involved took place in Medina, North Dakota, on February 13, 1983. State marshals attempted to arrest him at a nearby roadblock as he left a Posse Comitatus township meeting. Kahl realized that the police were close, and he traded clothes with his son Yorie to create a decoy; both of them were also armed. As expected, Kahl’s car, carrying other armed members of the township, was stopped, and an arrest was attempted. Although negotiations could have been made, Kahl, according to family accounts, refused to be taken alive and would sooner have been killed. The official report states that a member of Kahl’s group fired the first shot. Deputy Marshal Bob Cheshire and Deputy Jim Hopson were both killed, and Yorie was severely wounded and taken to the hospital once the firefight was over.

Kahl immediately fled North Dakota, traveling first to Texas and then to Arkansas, where he contacted fellow Posse Comitatus member Leo Ginter for help. By March, Kahl was hiding in Mountain Home (Baxter County) with a seventy-four-year-old man named Arthur Russell, who was also highly distrustful of the government. At times, Kahl left Russell’s house to visit Ginter’s residence in Lawrence County. Russell’s twenty-eight-year-old daughter, Karen Russell Robertson, uneasy that Kahl was staying with her father and hoping for reward money, alerted the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to the fugitive’s presence in the state. Her call was made on May 31, and, by June 2, the Ginter house was under FBI surveillance. By the next day, a plan had been put together to capture Kahl with the aid of two SWAT teams and several Arkansas state troopers—among them Lawrence County Sheriff Gene Matthews. With the house surrounded, Ginter tried to escape in his car but was stopped at the end of his driveway and questioned by the police; he stated that Kahl was not in the house. As Ginter was being interrogated, Matthews and Deputy Marshal Jim Hall moved around the side of the house and entered through a utility door.

What exactly happened inside the house is unknown and subject to much theorizing by right-wing conspiracy groups who believe that Kahl was brutally murdered. The official police report states that Matthews and Kahl fired at each other simultaneously and that Kahl was killed instantly by .41 caliber bullet to his head. Matthews was shot in the arm and the back by a shotgun blast but managed to tell Hall that Kahl was dead. Once Matthews was removed, police opened fire on the building; it caught fire and burned for two hours. Upon being arrested, Ginter admitted that Kahl had indeed been in his house for the last several days.

Kahl’s charred body was found in the wreckage of the house and taken to a funeral home in Walnut Ridge. An autopsy found that a bullet, not the fire, had killed him. Matthews also died that day from blood loss. A plethora of accounts of the life and death of Kahl continue to be shared today, especially by those who view Kahl as a martyr who stood against government persecution.

For additional information:

Corcoran, James. Bitter Harvest. New York: Viking Penguin, 1990.

Mathis, Toots, director. Death & Taxes. VHS, 1993.

Schnabel, Steve, and Darrell Graf. It’s All About Power! Fargo, ND: MPD, Inc., 1999.

Smith, Doug. “Leonard Ginter’s Struggle.” Arkansas Times, July 7, 1995, pp. 7, 20.

Terry, Bill. “Death of a Self-Styled Elijah.” Arkansas Times, January 1984, pp. 44–48, 102–107.

Bernard Reed

Little Rock, Arkansas

It took place in Smithville. I was seven years old at the time, and my mother and my grandmother were working in the garden at our Annieville home, which is two miles from where this took place. I remember hearing the automatic weapons.

I lived in Jonesboro at the time and took my family to camp at Lake Charles, near Strawberry, when this happened. There was total localand near-total regionaloutrage at what law enforcement did. The man was under siege in a bunker/house (underground on three sides), surrounded by dozens of law enforcement. Two officers went to a local farm and took gas from there despite the protests of the owner. They then burned that bunker. The conspiracy started when initial accounts from various branches of law enforcement officers didnt match.