calsfoundation@cals.org

French Explorers and Settlers

The French settlers’ experience in colonial Arkansas was vital to the history of the French presence in the Mississippi River Valley. The French settlers at Arkansas Post forged alliances and cohabited with the “Arkansas” Indians (Quapaw), the native inhabitants of what became Arkansas, who were known for their consistent loyalty to the French.

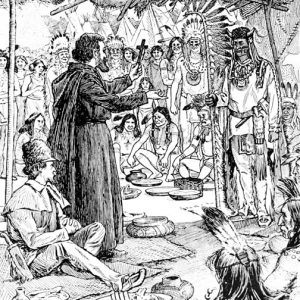

Father Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit, and Louis Joliet (or Jolliet), a trader, were the first Frenchmen to set foot in the Arkansas land, in 1673. They found four Quapaw villages: Kappa, Tongigna, Tourima, and Osotouy. Immediately, the two peoples entered into an alliance. Because they feared a potential alliance between the French and their rivals, the Tunica and the Yazoo, the Quapaw convinced the French to end their trip down the Mississippi River.

The Frenchmen were received with the ceremony of the calumet, “the peace pipe,” which was an important symbol of trust between national groups, whether they were alliances of two Indian tribes or Indian-European alliances. During the ceremony, all the participants exchanged gifts and passed and smoked the calumet. They used the ceremony to create kinship relations between the participants. Smoking the calumet bound the allies by sacred obligations toward one another, which explains Quapaw hospitality shown to the second French visitor, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, in 1682.

However, the first French permanent settlement, Arkansas Post, was set up by Henri de Tonti in 1686. By 1721, the French settlement counted forty-seven people. Despite the French government’s propaganda, few people ventured to the newly established colony, with the exception of “public girls,” coureurs des bois (“runners of the woods,” who engaged in the fur trade without French permission), and soldiers. The harsh climate, epidemics, floods, and isolation made the post “the most disagreeable hole in the universe,” according to Governor Bernardo Galvez. The French settlers and soldiers might have starved to death without the help of the natives.

The Quapaw remained vital to the survival of the French settlers in Arkansas. They were military allies and trade partners. The two nations also socially and sexually intermingled and intermarried. Jean Bernard Bossu, captain in the French navy, affirmed that it was “a pleasure seeing these women who were showing a great affection towards the French, they prefer them to the Spanish.” Sarasin, a Quapaw chief, was of mixed blood, born of a French father, Francois Sarazin, and a Quapaw mother. According to Governor Louis de Kerlerec: “The Arkansas [Quapaw] nation, without doubt the bravest of all those nations, they commenced to be attached to the French as soon as they knew them, and never varied in their attachment.”

The military alliance represented another facet of the cohabitation between the two peoples. The Quapaw were present in French campaigns against rival Indian groups who allied with the British. Without their Quapaw and Choctaw allies, the French would have undoubtedly had to abandon the Mississippi during the Natchez attack in 1729, as noted by Governor Etienne De Périer: “[The Quapaw] situation and their attachment to the French kept the English from passing the Mississippi after the Natchez Revolt.”

The French settlers and hunters at Arkansas Post were also targeted by both Osage and Chickasaw raids. As a result, in 1736 and 1740, the French-Indian alliance attacked the Chickasaw, erecting Fort St. Francis, near the mouth of the St. Francis River, to aid in these efforts. During the second expedition, Governor Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne De Bienville led an army composed of 1,200 soldiers, from both Louisiana and Canada, and a number of Indians. A number of Quapaw from Arkansas participated in this campaign. The chief of the Quapaw lost one of his sons and had another one wounded in the same war. On May 10, 1749, Arkansas Post was attacked by a group of about 150 Chickasaw warriors. They burned the settlement, killed men, and captured women and children. After the attack, the French moved the post to Ecores Rouges, a location to which the Quapaw had already moved.

Because Arkansas’s climate did not allow agricultural prosperity, hunting became necessary for the survival of the French settlers at Arkansas Post. As Captain Fernando de Leyba reported on the Arkansas settlers, “many of the farmers here are traders.” The French hunted buffalo for several purposes, but mainly for meat. Salted and sun-dried meat from Arkansas remained critical for both settlers and soldiers throughout the colony. The Arkansas French also exported buffalo tallow, necessary in the production of soap and candles. The settlers used buffalo hides to produce their clothing and to trade. The French also hunted bears for their oil and deer for their skin, both important to the economy of the colony.

The Treaty of Paris of 1763 marked the end of the French-Indian War and of French imperialism in North America. Spaniards took control over French Louisiana west of the Mississippi River, including the lands of the Quapaw. In 1768, the new governor, Antonio De Ulloa, announced that Louisiana would no longer trade with France. As a result, the French rioted in New Orleans, and a general revolt spread throughout the colony, including in Arkansas. In 1770, Francois Desmazellieres, commandant of the post, reported that “the habitants and Quapaws speak of nothing but abandoning the post.” He informed the governor that the chiefs of the Quapaw nation and the French inhabitants talked about their eventual settlement with the Osage. Shortly after, Alexander O’Reilly suppressed the rebellion of the French population.

Because of floods in 1779, the Spaniards removed the post and its settlers to Ecores Rouge again, where it remained. By 1791, the census reveals that the European population at Arkansas Post was 151 persons living in twenty-seven households. Among them, there were twenty-one French, five German, and one Spanish household, besides the American refugees of the American Revolution, who were not mentioned in the census. In 1801, Spain surrendered control of Louisiana Territory to France, which sold it to the United States in 1803. After the Louisiana Purchase, the land became a United States territory, signaling the end of the European colonial era.

For additional information:

Arnold, Morris. “Barthélémy Dit Charlot, a Colonial Arkansas Métis and Voyageur.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 74 (Spring 2015): 1–17.

———. Colonial Arkansas, 1686–1804: A Social and Cultural History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

———. “François Ménard, a Colonial Arkansas Marchard and Habitant.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 74 (Winter 2015): 303–326.

———. “The Métis People of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Arkansas.” Louisiana History 57 (Summer 2016): 261–296.

———. “Military Cooperation and the Relocation of Quapaw and French Settlements in Colonial Arkansas: A Case Study in Colonial International Relations.” Academic Papers (Arkansas Archeological Survey) 2003. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/aas_ap/1/ (accessed January 18, 2024).

———. “The Soldiers of France in Colonial Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Winter 2021): 403–435.

———. The Rumble of a Distant Drum: The Quapaws and the Old World. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Arnold, Morris S., and Dorothy Jones Core. Arkansas Colonials: A Collection of French and Spanish Records Listing Early Europeans in Arkansas, 1673–1804. DeWitt, AR: Grand Prairie Historical Society, 1986.

Dubuisson, Ann. “François Sarazin: Interpreter at Arkansas Post during the Chickasaw Wars.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 71 (Autumn 2012: 243–263.

DuVal, Kathleen. The Native Ground: Indians and Colonists in the Heart of the Continent. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Early, Ann M. “The Greatest Gathering: The Second French-Chickasaw War in the Mississippi Valley and the Potential for Archaeology.” In French Colonial Archaeology in the Southeast and Caribbean. Edited by Kenneth G. Kelly and Meredith Hardy. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2011.

Jeffers, Joe. “French Place Names in Clark County, Arkansas.” Clark County Historical Journal (2019): 13–27.

Jones, Linda C. “François Danbourné: Colonial Courier.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Spring 2021): 38–52.

———. “Language Encounters in Colonial Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 82 (Spring/Summer 2023): 23–27.

Jones, Linda Carol. Language Encounters on the French Colonial Mississippi: And a Few Regions Beyond. University of Arkansas, 2024. https://uark.pressbooks.pub/ethnohistoricapproachestonativeamericanlanguages/ (accessed August 22, 2024).

———. The Shattered Cross: French Catholic Missionaries on the Mississippi River, 1698–1725. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2020.

Kelly, Kenneth G., and Meredith D. Hardy. French Colonial Archaeology in the Southeast and Caribbean. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2011.

Key, Joseph. “‘Masters of this Country’: The Quapaw and Environmental Change in Arkansas, 1673–1833.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas 2001.

Sabo, George, III. Paths of our Children: Historic Indians of Arkansas. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 2001.

Toudji, Sonia. “‘The Happiest Consequences’: Sexual Unions and Frontier Survival at Arkansas Post.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Spring 2011): 45–56.

———. “Intimate Frontiers: Indians, French, and Africans in Colonial Mississippi Valley.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2012. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/344/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Walczynski, Mark. Jolliet and Marquette: A New History of the 1673 Expedition. Champaign, IL: 3 Fields Press, 2023.

Sonia Toudji

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.