calsfoundation@cals.org

Farm Resettlement Projects

aka: Resettlement Administration

aka: Farm Security Administration

Many of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs were implemented to help farmers and rural residents weather the effects of the Great Depression. These programs allowed a succession of federal agencies to develop farming colonies throughout Arkansas.

In an effort to assist rural residents and tenant farmers, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) urged each state to establish a Rural Rehabilitation Corporation. William Reynolds Dyess, Arkansas’s director of both the FERA and Works Progress Administration (WPA), created this assistance in Arkansas. Under the auspices of the Arkansas Rural Rehabilitation Corporation, Dyess sought to develop a swampy section in southwestern Mississippi County as a planned agricultural community. FERA administrator Harry Hopkins approved the plan in early 1934, and the corporation purchased 15,144 acres of swamp and unimproved timberland. Colonization Project Number 1, which would settle destitute farm families on plots of land in an effort to set them up as independent farmers, was established in May 1934. Little Rock (Pulaski County) architect Howard Eichenbaum designed the simple, functional houses—wired for electricity, and in several different layouts—for the colony. Each farm would also have a barn and chicken house, in addition to other outbuildings.

The colony, which eventually totaled 17,500 acres, was divided into 500 twenty-acre units. A city center—which included an administration building, commissary, canning center, theater, and school—was established. The colony was renamed for Dyess after his January 1936 death in an airplane crash, and some 482 families lived in the colony when it was formally dedicated on May 22, 1936. Completed at a cost of $4,233,045, Dyess Colony stopped recruiting new colonists in January 1939, and many of the colonists eventually paid off the federal loans on their farms and became, as Dyess had imagined, independent farmers. The Dyess Colony Center was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 1, 1976, and parts of the town have been restored through Arkansas State University’s Heritage Sites program.

On April 30, 1935, through Executive Order 7207, Roosevelt combined several rural relief agencies into the Resettlement Administration (RA), which was created to provide financial assistance for poor farmers, establish resettlements for migrants and farm workers, and perform farm conservation activities; the RA was a desperately needed agency in Arkansas, which ranked sixth in the U.S in farm tenancy. Rexford Tugwell, a close associate of the president, led the agency, which he divided into several regional organizations. Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana became Region VI.

The first RA project completed in the United States was Plum Bayou near Wright (Jefferson County), where 9,854 acres of river bottomland in Jefferson County were divided into 183 forty-two-acre units. It was dedicated on November 20, 1936, and 183 families were selected to live in houses that featured electrical wiring, running water, and light fixtures. Each homestead also had its own well, barn, and pasture. Development of Plum Bayou cost $1,589,893.44. Plum Bayou was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 5, 1975. The RA also established the Lakeview Resettlement Project in Phillips and Lee counties for black farmers, setting up 142 units on 8,163 acres of land, much of which the U.S. government had foreclosed on. Lakeview cost $892,619.11 to develop, and it opened in 1937. The town of Lake View was later incorporated at this site.

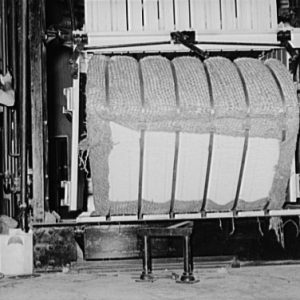

The RA modified the farm resettlement pattern that had been established at the Dyess Colony and had continued at Plum Bayou and Lakeview when it developed the settlement at Lake Dick near Altheimer (Jefferson County). While the earlier projects had established individual homesteads with attached farmland, Lake Dick followed a European model in which everyone lived in a common village and went out to work in the fields. The town held eighty houses, a community center, a meat-curing plant, a potato storage barn, a sorghum mill, a warehouse, and mechanical shops. Lake Dick consisted of 4,523 acres in Jefferson and Arkansas counties divided into eighty-nine units and developed at a cost of $661,670.64. The Lake Dick Farm, Inc., association rented the land from the federal government, and membership in the association allowed the families to have ownership interest in the land and facilities. Lake Dick was listed on the National Register on July 30, 1975.

In addition to the RA-generated projects, the agency also inherited resettlement projects that had started under FERA through the Arkansas Rural Rehabilitation Corporation. These included two in Poinsett County: Trumann, which had fifty-five units on 2,224 acres and cost $263,229.44, and St. Francis, a $530,176.20 project with seventy-two units on 3,971 acres. Central and Western Arkansas Valley Farms, originally two separate projects, held eighty-two farm units scattered through Conway, Crawford, Faulkner, Franklin, Johnson, Logan, Pope, Sebastian, and Yell counties; totaling 6,916 acres, the project cost $344,183.93. Northwest Arkansas Farms in Benton and Washington counties encompassed 3,233 acres split into forty-four units at a cost of $211,711.36. Arkansas Farm Tenant Security, with farms in Clark and three other counties, consisted of 4,508 acres in sixty-six units costing $476,950.24.

Two other projects started by the Arkansas Rural Rehabilitation Corporation were located in southeastern Arkansas. Chicot Farms held 13,781 acres in Chicot and Drew counties split into eighty-nine units, which included the entire town of Jerome (Drew County). It was developed at a cost of $568,692.81. Kelso Farms consisted of 7,582 acres in Desha County, purchased for $43,333.41 but never developed as a farm resettlement project. The farms were leased to the War Relocation Authority after World War II began, and the sites would house Japanese American citizens in the Jerome and Rohwer internment camps; Jerome would also house prisoners of war.

Using grants and resettlement funds, the RA in 1936 began another project, called Arkansas Delta Farms, that resulted in five other resettlement efforts—three for white farmers and two for African-American farmers. The largest was at Clover Bend (for white farmers) in Lawrence County, where 4,995 acres were purchased for $460,701.28 and divided into eighty-six units of forty to sixty-five acres, depending on the size of the family farming the unit. (Clover Bend High School was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 17, 1983, and the Clover Bend Historic District was listed on September 17, 1990.) The other Arkansas Delta Farm resettlement projects for white farmers were Biscoe Farms in Prairie County—where 4,530 acres were split into seventy-four units at a cost of $372,005.60—and Lonoke Farms in Lonoke County, consisting of 2,903 acres divided into forty-one units and costing $251,964.15. The two resettlement farms for black farmers established through the project were Desha Farms in Desha and Drew counties, made up of 4,422 acres split into eighty-eight units for $515,039.95, and Townes Farms in Crittenden County, with 1,921 acres in thirty units at a cost of $163,679.79.

Following the passage of the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act, which authorized a modest federal loan program to help tenant farmers buy land, the RA was abolished on September 1, 1937, and became the Farm Security Administration (FSA) under the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Administratively, the FSA was the same as the RA, with many of the same personnel, but it had the added duties of administering the loan program of the Bankhead-Jones Act and helping farm families become more self-sufficient. The FSA also continued a photography program started under the RA that resulted in a remarkable visual record of the Great Depression. In 1946, the FSA was absorbed into the Farmers Home Administration, which continued to administer federal farm programs until 2006 when its duties transferred to USDA Rural Development.

The New Deal farm resettlement projects provided stability in a time of crisis for many of Arkansas’s rural and farm families, as well as a path to land ownership for some. The surviving buildings and farms associated with the projects remain as testaments to the Roosevelt Administration’s far-reaching efforts to assist rural Americans in the depths of the Great Depression.

For additional information:

“Clover Bend High School.” National Register of Historic Places from. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/arkansas-historic-preservation-program (accessed June 14, 2023).

“Clover Bend Historic District.” National Register of Historic Places from. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/arkansas-historic-preservation-program (accessed June 14, 2023).

Covey, Reta Goff. “History of Clover Bend.” Lawrence County Historical Quarterly 2 (Summer 1979): 5–16.

“Dyess Colony Center.” National Register of Historic Places from. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/arkansas-historic-preservation-program (accessed June 14, 2023).

Henson, Everett Dewey. “Memories of Dyess Colony.” Delta Historical Review 2, 1990, 3–21.

Holley, Donald. “Trouble in Paradise: Dyess Colony and Arkansas Politics.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Autumn 1973): 203–216.

Holley, James Donald. “The New Deal and Farm Tenancy: Rural Settlement in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi.” PhD diss., Louisiana State University, 1969.

———. Uncle Sam’s Farmers: The New Deal Communities of the Lower Mississippi Valley. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975.

“Lake Dick.” National Register of Historic Places from. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/arkansas-historic-preservation-program (accessed June 14, 2023).

Pittman, Dan W. “The Founding of Dyess Colony.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Winter 1970): 313–326.

“Plum Bayou Homesteads.” National Register of Historic Places from. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/arkansas-historic-preservation-program (accessed June 14, 2023).

Walls, Ernestine. “Lake Dick & Plum Bayou New Deal Projects.” Jefferson County Historical Quarterly 41 (March 2013): 29–35.

Mark K. Christ

Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.